The Hollywood staple in sports films is typically inextricable from some facile metaphor about the American Dream: pure determination predicts real success. Work hard, and you’ll make it on to the team. Believe in yourself, and you can overcome racism. Train hard enough, and you may even defeat communism. Yet for this week’s movie recommendation, in what is possibly the greatest sports film of the twentieth century, iron resolve and the American Way is nothing less than the source of the main character’s complete downfall. It’s Robert Rossen’s The Hustler (1961).

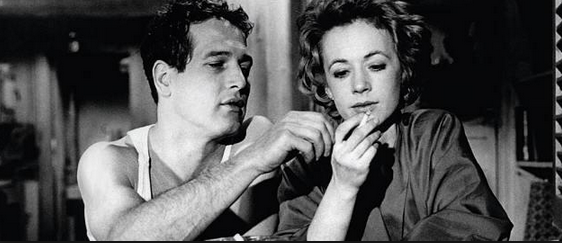

A young Paul Newman plays the dashing ‘Fast’ Eddie Felson, a pool player who fails to understand that his impressive knack with a cue isn’t the same as being able to win. Felson is a small-time hustler with an eye toward playing in the big leagues. His ticket to get there is a victory against the top pool shark in the land, Minnesota Fats (played by Jackie Gleason). After Felson calamitously loses to Fats, he learns that you need a lot more than just an ability to ‘play a good stick’ when you’re the other side of a 25-hour marathon; you need endurance, ‘character,’ and the knowledge that…

This game isn’t like football. Nobody pays you for yardage. When you hustle, you keep score real simple. At the end of the game, you count up your money. That’s how you find out who’s best. It’s the only way.

During Felson’s spiral into despondency, he betrays his close friend Charlie (played by Myron McCormick) and falls into both the loving arms of Sarah Packard (played by Piper Laurie) and the dastardly machinations of gambler Bert Gordon (played by George C. Scott). Although Bert at least has the decency to tell people that he’s making a buck at their expense, the hustles are in fact ubiquitous. Indeed, the deceptions have become such a way of life that the distrust infects even Sarah and Eddie’s relationship. If Eddie is going to beat Fats, it’s going to come at the expense of whatever innocence he has left – or that he might hope to recover through his connection to Sarah.

Sure enough, at one point Eddie has to scrounge a cash stake by sneaking money away from Sarah during her own period of acute vulnerability, as she is drunk and unconscious at a stranger’s home. The choice between either protecting his love or pursuing his game is made as easily as it was earlier, when he similarly betrayed Charlie.

Bert’s incomparable wickedness means that he is only too happy to facilitate Eddie’s demise. He sees Sarah as an inconvenient distraction from Eddie’s ability to earn money on his behalf, and he effortlessly dispenses with her with little more than a few well-placed barbs. The screenplay thankfully devotes ample attention to the important sub-plot between Bert and Sarah. The impressive power-play between these two characters forms of one of the most affecting scenes, when Bert returns to the hotel before Eddie, fresh from their most recent hustle, and seduces Sarah after Eddie’s recent betrayal. Between Bert’s connivances and Eddie’s negligence, Sarah doesn’t stand a chance.

During the final showdown with Fats at the film’s denouement, we see exactly where Eddie is headed. The chasm that separated the two characters at the beginning of the film has disappeared: in Fats’ perpetual expression of resignation (Gleason’s eyes betray palpable melancholy), we see that he, too, has been broken down by the years of hustle – he is as much a victim of Bert’s extortion as was Eddie. Fats doesn’t need to hide that he’s the best in the business; instead, the form that his indignity takes is that the hustle has reduced him to one of Bert’s props. Fats sits by and listens as Bert and Eddie exchange verbal blows, familiar as he is with the waltz the two are dancing – he’s done it himself. It’s the dance of people giving up their souls to the hustle.

Rossen’s adaptation of the Walter Tevis novel of the same name thankfully doesn’t suffer from Felson’ hubris: the direction is admirably restrained and deftly executed. However, at times the religious allegory is piled on pretty thick (for another instance of this, see Newman’s performance in Cool Hand Luke, reviewed here). Not only is Felson’s search for redemption a preoccupying theme but the reverence for the hustle and its participants is positively ecumenical (the hallowed billiard hall in which Eddie will battle with Fats is the “Church of the Good Hustlerâ€). If the Manichaean characters aren’t yet abundantly apparent, Bert is compared to the devil during the scene immediately preceding his consignment of Sarah to oblivion, whereas Eddie’s thumbs are broken as crucifixion for the sin of having hustled inexpertly.

The Hustler garnered nominations – but no awards – from the Academy for all four of its main cast members. I’ll soon review the sequel from two and a half decades later, when Newman earned his only Oscar – reputedly in apology for having been passed over in The Hustler.

Johann — you throw new light on this film. I remember vividly Bert “explaining” things to Felson: You. owe. me. MONEY!

Newman made this film, Hud and Hondo — all fine movies. When he then appeared in Archer, based on the detective novels, (another fine movie) they changed the title to keep his H-lucky streak alive by calling it Harper.

Will be curious what you think of the Color of Money. I thought that Rossen’s restrained, economical style was a better match for Newman’s gifts than Scorcese’s flashy colorful operatic bravura etc. style.

The story, according to Piper Laurie: “George had a big argument with Rossen about that ['You owe me MONEY!']; Rossen did not think that was the right reading. He wanted a more conventional ‘You owe me money.’ But George insisted on doing it his way, and he did.”

A few notes on your excellent selection:

1. "Felson is a small-time hustler with an eye toward playing in the big leagues. His ticket to get there is a victory against the top pool shark in the land, Minnesota Fats (played by Jackie Gleason)."

Back in the day, there was no money in pool tournaments. Thus, it's not clear what financial value there was in "playing in the big leagues." In fact, as a hustler, it was a huge negative. If you became "the guy who took down Fats," you couldn''t hustle a game anywhere in the USA. The Big Leagues, then, was a phrase meaning you had been recognized as one of the best, and your future source of pool-playing income was only by playing some pretty good, and very wealthy, opponents who wanted to test themselves against the best. Thus, the segment with the match at Findley's home is crucial to the film.

2. "Eddie’s thumbs are broken as crucifixion for the sin of having hustled inexpertly."

I wouldn't characterize Eddie's sin as having performed his craft (hustling, not pool playing) inexpertly. While he was doing it (hustling), he did it exceedingly well.

Rather, I'd say his sin was allowing pride to overcome his pursuit of his craft. At the moment he revealed himself to those guys as a hustler, he had forgotten that his craft was hustling, and had wanted them to recognize how good he was at pool-playing. Why he would care that a bunch of run-down guys in some run-down joint might recognize how good a pool-player he was remained a mystery to Eddie, but it is revealing of what it meant to him to be in The Big Leagues. It was his fatal tragic flaw-more important than succeeding, either at pool OR hustling, the driving force in his life was the need to be recognized as a "Big Leaguer."

3." the hallowed billiard hall in which Eddie will battle with Fats is the “Church of the Good Hustler” …"

Ames, the large bland-looking pool room just off Times Square, was just that. A teen-ager who shot a fair stick, one weekend I took the train from college in central New Jersey to The City to find out how good I was. Ames was the destination, of course, and that was two years before The Hustler put it on the map for "civilians." I found out, and the lesson was quick and painless. It was quick because a fair stick from Baltimore going into Ames was like a piranha going for a meal in the midst of a feeding frenzy of great whites. And it was painless because I went with a small roll and no credit, and had no expectations-just a willingness to lose my small roll if that's what it took to test myself.

55 years later, I am still sad that Ames (and its ilk) disappeared from the American scene.

We keep telling the same story over and over again. Wolfenstein and Leites (1950) write about it as basis of 1940s noir films, which they saw as Oedipal: ‘ . . a night-time dream world . . . where the hero is involved in a conflict of crime and punishment with the older man, his boss, often the lord of the underworld.” In this case, that’s Burt (George C. Scott) who controls not only Fats but seemingly the guys who break Eddie’s thumbs (which the Freudian Wolfenstein and Leites would surely see as castration).

Charlie, Eddie’s first manager, is the functional equivalent of the noir hero’s father: “usually a sympathetic character, and almost always ineffectual.” As for the girl, W&L say that in the “night-time world . . . the hero grapples with a dangerous older man and wards off entanglement with a desirable and yearning woman.” Eddie doesn’t ward off such entanglement, but the film makes clear that it is not until he is free of this entanglement that he can successfully confront the boss of the underworld. Which of course he does in the inevitable showdown (as in Brando v. Cobb in “Waterfront”).

The recent “Whiplash” is another retelling of this story – drumming instead of pool, J.K. Simmons instead of George C. Scott, Paul Reiser for Myron McCormick. (FWIW, my blog post about "Whiplast" is here.) And just as “Whiplash” is misleading about how people actually learn to play jazz, “The Hustler,” as RhodesKen says, is misleading about how hustlers worked in the pre-tournament world. Ned Polsky had a nice article about this, later collected in his book Hustlers, Beats, and Others..

Also, if you watch “The Hustler,” make sure you get the original aspect ratio. The recut-for-TV version loses so much of the beauty of the way Rossen frames the shots. Stick with this film, Fats. It’s a winner.

Back when, I paired The Hustler and The Cincinnati Kid (both the books and the movies): they had similar themes; the movies starred icons (Newman and McQueen). The Hustler was a better movie, I now think. And it's been so long (50 years?) since I read either book that my memories of them are increasingly unreliable.

With The Cincinnati Kid, they tried to remake The Hustler with poker, and the best movie about poker was still… The Hustler. California Split probably has the superlative for realism, though.

Actually, the movie was a pretty straight screen version of the book. So maybe Richard Jessup (who wrote the book) was re-writing Walter Tevis (who wrote the other book).

The movie of The Cincinnati Kid is pretty faithful to the Richard Jessup novel…which, on the other hand, he may have written as are-make of the Walter Tevis novel, The Hustler…

Noted and noted. The straight flush over aces full was a little too much for me if the point was to be "be wary of trading your integrity for your dreams" instead of "The Man always wins." I haven't seen The Cincinnati Kid in about nine years – and I wasn't even aware it was an adapted screenplay – so my memory is a little thin on that one. And we did get In the Heat of the Night from Jewison a few years later.