Like most people who write about trends in incarceration, I generally focus on how the size and nature of the entire U.S. prison population changes from year to year (e.g., here). This sort of analysis can reveal important things, for example that after rising every year for more than three decades, the size of the prison population has been dropping for three years in a row. But at the same time, such analyses tell us little about what state and federal policymakers are doing regarding prisons right now.

All policymakers are at some level trapped by decision accretion, and prisons are a perfect example of the phenomenon. The high level of incarceration in the U.S. is the product of decisions made over many years prior to when the current group of policymakers was on the scene. For example, while I have complained about the abolition of federal prison parole as a cause of overcrowding, I also recognize that many of the elected officials who voted for it have died of old age, and hardly any are still in office. Even if the current Congress re-established parole tomorrow, it would take years to unring that bell. Likewise, people who have committed heinous crimes for which they are serving multi-decade sentences do not simply evaporate with each election. And that’s critically important in evaluating how quickly current policymakers can reduce incarceration levels given that the majority of the state prison population is composed of violent offenders who are serving long sentences.

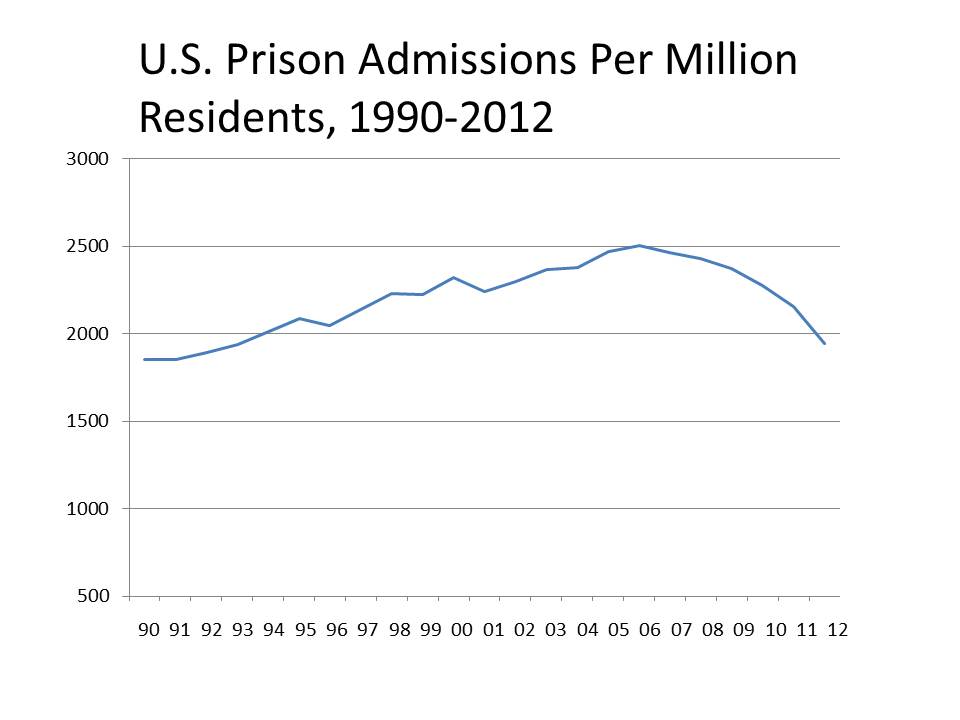

To try to get around this analytic problem of decision accretion swamping recent trends, I used the latest Bureau of Justice Statistics data to compute the annual rate of admissions to state/federal prison. As the chart below reveals, the large amount of recent change in this variable was obscured in my prior analyses, which looked only at total prison population size. I was startled and encouraged to see that under current policies, we are at a two decade-year low in the prison admission rate. To provide historical perspective, peg the change to Presidential terms: When President Obama was elected, the rate of prison admission was just 3% below its 2006 level, which was very probably the highest it has ever been in U.S. history. But by the end of Obama’s first term, it had dropped to a level not seen since President Clinton’s first year in office.

This is an impressively rapid and sustained change, and seems to coincide with the Great Recession. Speculating, could this be prosecutors finally responding to prison costs, and using their discretion to go for sentences that do not involve further incarceration? I’m assuming that many defendants will have already spent time in jail.

@DCA: Historically, the prison population grows during recessions just as it did during The Great Depression.

https://thesamefacts.com/2013/07/crime-control/prisons-and-penal-policy/recessions-do-not-cause-reductions-in-the-prison-population/

However some things are different today, most particularly the dramatic drop in crime, which lowers voters’ fear of crime and gives politicians room to maneuver. It also helps that many conservatives have re-thought their commitment to prison, allowing some bipartisan coalitions to reduce the population.

They say it takes miles for a supertanker to change course, to say the least, the largest ship of state known to history. Since before BHO first took office I’ve sensed a great change toward “reason” in the world, the last negative vestiges of which were the whimperings of the Great Tea Party.

This may be the first definitive indication of the “final report” made on this era. I wonder what correlations to reality are next? Whatever they are will well describe the effectiveness of social media in leveraging the great “democratized thought space” that it has engendered where reason ultimately prevails (i.e., the world where too long threads ultimately devolve into references to Hitler).

P.S. Being a cybersecurity consultant to the nuclear industry, my “key indicator” of change is when those in control finally allow that Fukushima, with its continued triple unconstrained meltdowns, will require the combined efforts of the major nuclear powers to quell (via robotics). Note, that will only happen upon their acceptance of accountability for dry cask sequestration & other “required remediations,” the costs of which will obviate the entire industry’s economic model.

Nice analysis.

In the jargon of my field, it is a “stocks and flows” system, and you’ve shown data on the flow, whereas most people focus on the stock. Flows change faster than stocks.

To add to the list of candidate hypotheses — US cocaine consumption (including crack) fell radically starting around 2006, in total by 50%. Cocaine had accounted for well over half the spending on the “big three expensive” drugs (heroin, cocaine/crack, meth) that account for the great bulk of drug-related crime. (Marijuana is widely used, but is much less tied to crime.) I grant that there has been a widespread desire to step back from excessive imprisonment, but the decline in cocaine use & distribution could also contribute. One might get some handle on whether it is tight budgets, shrinking cocaine, or something else by looking at state-specific trends.

Excellent points Jon. The BJS report show that drug-related prison admissions are decreasing particularly quickly. As you know, those individuals tend to receive shorter sentences than violent criminals, so they are more flow than stock.

If the graph showed admission rates per reported crime levels, it would have a very different slope. Still, it’s good news.

One thing I’ve wondered about is if the difference in parental role models will have an even greater effect in the near future. The fathers and older siblings of the youngest teens today are likely to have committed fewer crimes than the fathers of teens a decade earlier. Will that help?

I encourage you all to read this article in its entirety:

“The curve of epidemic imprisonment in America has now begun to inflect and a growing number of states are now intentionally shrinking their prison populations in favor of alternatives to incarceration, especially for juveniles and drug offenders. 21

New York, the first state to employ long mandatory sentencing for drug offenses with its “Roc kefeller drug laws†of 1973, 22 is now leading the nation in reform. Indeed, New York State now has the nation’s largest percent drop in its prison population since the 1990s—from 73,000 inmates in 1994 to 58,000 in 2012—a decline of over twenty percent. 23 In New York, we can already see that this drop is due to changes in two important expressions of policy: the number of felony drug arrests and the patterns of mandated long sentences that have accompanied them, along with the repeat imprisonments that these policies made inevitable. 24 Felony drug arrests alone have dropped twenty percent in New York State since 2008, leading to declines in associated prosecutions, convictions, and imprisonments.” https://law.uoregon.edu/org/olr/volumes/91/2/documents/Drucker.pdf

Unfortunately there remain some worrying trends:

“Indiana’s prison population has increased by 5.3% -more than any other state- from 2008 to 2009, despite the first decline in nearly 40 years in state prison populations nationwide.”

http://www.in.gov/portal/news_events/71648.htm

Indiana wants me.

Lord, I can’t go back there…

It’s a very unusual graph. It must be rare to see such an unequivocal reversal of a long-term trend round a unique discontinuity. The fall is twice as fast as the rise. Maybe Kevin Drum’s “It’s the lead, stupid” theory of crime trends is right.

The fall is striking. The drop in both 2007 and 2008 were very small, less than 10,000 admissions total. But the drop in 2009 was larger than 2007 and 2008 put together and then the drop in 2010 was larger than 2007, 2008 and 2009 put together.

Here is Kevin’s take on how lead plays into all this.

http://www.motherjones.com/kevin-drum/2014/01/chart-day-fewer-people-are-being-sent-prison-way-fewer/

What about the jail admissions rate?

Good point. California’s shift of populations from prisons to jails could account for some of this.

jail populations noted here:

http://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/jim12st.pdf

Big increase in midyear 2012 California jail population from year-end 2011, but still well below the midyear 2009 figure.

The transfer of prisoners from state to local facilities would not affect the numbers in my graph because they were still admitted as state prisoners.

Do you have this parsed by state (or at least for California)? How did you do the calculations?

I have monthly Average Daily Population figures for California, but haven’t yet found admissions data. I’d love to replicate for California.

@Brain Sala: I think the state by state data is in the BJS report I linked to, though I am not 100% sure. The calculation is just admissions divided by population in the same year, which you can get from the census bureau. Please post your results if you follow through on this.

I see the problem. Your link is to BJS’s _Correctional Population in the United States_ series. But as best as I can see, these reports only offer point-in-time head counts. I’m completely missing where in the reports they detail admissions (and releases). Your intended reference (presumably) was to “Prisoners in 2012: Trends in Admissions and Releases, 1991-2012,” by E. Ann Carson, Daniela Golinelli. December 19, 2013 NCJ 243920. http://www.bjs.gov/index.cfm?ty=pbdetail&iid=4842

unfortunately, the zip file linked on the report’s landing page that is supposed to have the data instead is for admissions/releases from parole and probation (http://www.bjs.gov/index.cfm?ty=pbdetail&iid=4844). Looks like I’ll need to chase down Ms. Carson for the correct data links.

Thanks Brian you are correct. I have fixed the link.

This is a very helpful way to look at the issue. I wonder about the conclusion that the “stock” of prisoners will stay high despite falling admission “flows” because of the many prisoners serving long sentences. One can hope that in the not-too-distant future policies such as compassionate release, geriatric parole, executive clemency, or even retroactive sentencing changes may be used to address this issue. The combination of high per-capita costs to incarcerate older and (generally) sicker people, the well-known decrease in recidivism among older people when released, ongoing advocacy by prisoners / families / allies, and maybe even a further conservative turn towards “redemption” or “right on crime” could all contribute to such a future shift.

It’s a great question to think about and it’s complicated because you have hundreds of thousands of people of different types flowing in and out of the system each year. I agree with you that there is space to expand compassionate release, which is what Holder has proposed but thus far according the DOJ IG the FBOP has not acted on it.

You’re right that the prison admission rate is at a two-decade low, but this is only part of the story. Looking at the admission rate beginning in 1990, it would appear that we’ve ended an anomalous spike. But if you extend your perspective to 1979 – using all of the data in the Bureau of Justice Statistics report – then it’s quite a different picture. Within this broader historical context, the prison admission rate remains dramatically high: 2012’s rate is over one and a half times higher than that of the tough-on-crime 1980s.

See chart here: http://sentencingproject.org/images/photo/U.S.%20…

The other part of the story is releases. While it's true that releases have slightly outpaced admissions for the last several years (and largely affected by CA), unless those figures increase substantially it won't be possible to see any significant overall reductions in the total prison population.

That’s why a more comprehensive look at admissions and releases in historical context offers only modest cause for optimism (see: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/marc-mauer/88-years….