My reaction to Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring in the Mauritshuis museum in The Hague surprised me. I was expecting to admire this famous work by a great master, the favourite painting of the Dutch. It is indeed technically marvellous. Vermeer was one of the greatest technicians of oil painting ever. My problem with the picture is as a portrait. It’s formally a tronje, a painting of an unidentified and representative human figure. But it’s plainly not a stylised ideal but a portrait of a real girl. She has no name, perhaps (as in the film) a servant paid a few ducats to sit. I find it unflattering, and not by any lack of skill. Newspapers rightly get criticised for printing photos of politicians with their mouths open: everybody looks stupid when caught like this. Vermeer went to enormous trouble, over multiple sittings, to make his subject look dimwitted. She was exophthalmic anyway, and he faithfully reproduced or exaggerated this. The combined effect is disrespectful and exploitative. And to what purpose? Possibly to make a trite contrast with the perfection of the enormous pearl earring lent her for the occasion. Pshaw.

My reaction to Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring in the Mauritshuis museum in The Hague surprised me. I was expecting to admire this famous work by a great master, the favourite painting of the Dutch. It is indeed technically marvellous. Vermeer was one of the greatest technicians of oil painting ever. My problem with the picture is as a portrait. It’s formally a tronje, a painting of an unidentified and representative human figure. But it’s plainly not a stylised ideal but a portrait of a real girl. She has no name, perhaps (as in the film) a servant paid a few ducats to sit. I find it unflattering, and not by any lack of skill. Newspapers rightly get criticised for printing photos of politicians with their mouths open: everybody looks stupid when caught like this. Vermeer went to enormous trouble, over multiple sittings, to make his subject look dimwitted. She was exophthalmic anyway, and he faithfully reproduced or exaggerated this. The combined effect is disrespectful and exploitative. And to what purpose? Possibly to make a trite contrast with the perfection of the enormous pearl earring lent her for the occasion. Pshaw.

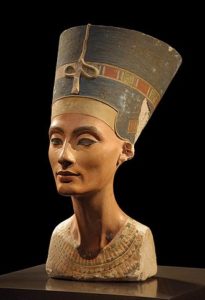

My second portrait is an extreme contrast: Nefertiti, Queen of Egypt for almost 20 years, in Berlin. Again, the extraordinary technical skill of the bust (about two-thirds life size) is indisputable. The effect is remarkable. She is not just beautiful but glamorous: beauty weaponized. (The origins of the word lie in Scottish witchcraft.) For what purpose? The classic glamour photos of Hollywood studio stars were designed to transform their exploited and vulnerable subjects into unattainable objects of sexual desire, in order to sell film tickets. Nefertiti didn’t need that; she was a Pharaoh’s queen already.

My second portrait is an extreme contrast: Nefertiti, Queen of Egypt for almost 20 years, in Berlin. Again, the extraordinary technical skill of the bust (about two-thirds life size) is indisputable. The effect is remarkable. She is not just beautiful but glamorous: beauty weaponized. (The origins of the word lie in Scottish witchcraft.) For what purpose? The classic glamour photos of Hollywood studio stars were designed to transform their exploited and vulnerable subjects into unattainable objects of sexual desire, in order to sell film tickets. Nefertiti didn’t need that; she was a Pharaoh’s queen already.

The Hollywood stars were metaphorical sex goddesses. Nefertiti was the real thing.

First, the sex part. There is no reason to doubt her depicted beauty. Her husband Amenhotep was portrayed as ugly, with distended belly and elongated limbs, possibly as a result of a congenital condition. So the burden of regal show, and quite likely of day-to-day rule, fell disproportionately on the queen. She rose to the challenge; she even had herself sculpted naked, a radical step in any culture that you can only get away with if you have a great body and total self-confidence.

Second, the goddess. Pharaohs and their consorts were semi-divine personages anyway, on speaking terms with the gods. But Amenhotep IV – Akhenaten – was determined on a religious revolution. He swept away the pantheon, and replaced it by a proto-monotheistic cult of Aten, represented only as the solar disc. The worship of Aten was carried out in courtyard temples open to the sky, not dark labyrinths. The Pharaoh and queen became the unique intermediaries between the people and Aten, and the priests were out of a job. They did not appreciate this, and after Akhenaten’s death staged a successful counter-revolution. His son Tutankhamun (by another wife) was buried surrounded by images of the old pantheon. The Aten cult was forgotten, the new capital at Amarna abandoned. While it lasted Queen Nefertiti was a sacred priest-empress, as near to a goddess as monotheism allows.

Second, the goddess. Pharaohs and their consorts were semi-divine personages anyway, on speaking terms with the gods. But Amenhotep IV – Akhenaten – was determined on a religious revolution. He swept away the pantheon, and replaced it by a proto-monotheistic cult of Aten, represented only as the solar disc. The worship of Aten was carried out in courtyard temples open to the sky, not dark labyrinths. The Pharaoh and queen became the unique intermediaries between the people and Aten, and the priests were out of a job. They did not appreciate this, and after Akhenaten’s death staged a successful counter-revolution. His son Tutankhamun (by another wife) was buried surrounded by images of the old pantheon. The Aten cult was forgotten, the new capital at Amarna abandoned. While it lasted Queen Nefertiti was a sacred priest-empress, as near to a goddess as monotheism allows.

Did the cult die? Sigmund Freud for one thought not. He suggested that the Aten religion influenced Jewish monotheism. Archaeologists pooh-pooh this. The Egyptian captivity is generally considered unhistorical; all the evidence points to a Canaanite origin for Judaism. But in that case, where did the story of the Exodus come from? Canaan was often a frontier province of the Egyptian empire. Metropolitan political and cultural upheavals would have filtered there during Akhenaten’s quite long reign (ca. 1350 BCE) . A contribution to early Jewish developments is certainly possible – it’s more believable than the bloodthirsty fantasies of the unread Book of Joshua. Once you ask “Why not one?” the question is hard to put away.

Maybe Nefertiti is still our Queen.

* * * * *

PS: If you enjoyed my offbeat art history, you might take a look at some older posts on women subjects and great artists: Bernini, Botticelli, Ghirlandaio, Michelangelo.

I believe Canaan was also a source of cheap labor for Pharaohs fixated on great building projects. When times were hard up north in Canaan, people apparently migrated down to Egypt in search of jobs and food. Not inconceivable that some of these Canaanite indentured laborers fell under the sway of monotheism, to a greater or lesser degree, and at some point decided to migrate back home. Ramesses (a named Pharaoh in the Old Testament) had some major construction projects underway, and there might have been a kerfuffle of sorts when a subset of the laborers decamped. Nothing on a scale to show up in the official records, but a possibility. Reconciling the Torah with history means exploring possibilities with little hope of certainties.

Ramses II was a hugely successful monarch with a very long reign. He still has name recognition after 3,000 years. The shades of such men hoover up historical events they had no part in, just all the bons mots get attributed to H.L. Mencken or Oscar Wilde.

Very interesting post. “Girl” doesn’t look stupid to me at all. I agree though it is rather rude not include someone’s name on a portrait of an individual. (The concept of tronje was new to me, and I had to look up exo-whatsit too … plus, there again, I must disagree, her eyes look pretty normal imo - it is the angle that makes them seem large.) To me her mouth being open just seems like she was caught in the act of something.

Nefertiti to me looks okay. Certainly symmetrical and well-proportioned and all that. I sense no allure though. Perhaps it is a gender thing?

I often have reactions to portraits … especially female nudes, which almost always annoy me immediately. Not these though. Of course it is silly to get annoyed that easily, but oh well.

Anyhow, thanks for showing me two beautiful works of art. Portraiture is one of the things Worth Doing.

She is not just beautiful but glamorous: beauty weaponized.

I sense no allure though.

Glamor, like humor, is in the eye of the beholder.

Whew, do I ever disagree with this! Well, about Nefertiti, sure, I think you nail it well. But the Girl? I think you're just flat-out wrong. She's gorgeous, and certainly doesn't look dull-witted at all. Her eyes look entirely normal, and Vermeer got her mouth perfectly. I'm not alone in thinking that: there's a reason she's often called the Mona Lisa of the North. I saw her up close when she took a vacation to San Francisco, and found myself transfixed for an hour (alas, an uncomfortable hour, given the approximately 200,000 other visitors crowding into the de Young that day).

By the way, years ago I read a quite wonderful analysis that strongly suggested the Girl was one of Vermeer's daughters, and indeed may well have been a painter herself (albeit not a genius like her dad). First, he hung onto the Girl right until his death in 1675, despite desperate poverty. So this painting was important to him. Second, there's another portrait ascribed to Vermeer, Girl With A Red Hat, that the author said was possibly the same model a few years later … and, he thought, very possibly it was a self-portrait. The author noted it was not nearly as skillful as a real Vermeer should be, yet was nonetheless skillful and positively associated with the Vermeer household. Alas, I have no idea who wrote that analysis — it's been 4-5 years since I read it, and a quick search on the intertubes gave me no joy.

P.S. — Hey, I found it! Or, at least, a Guardian article from 2009 about the scholar who argues that the Girl was Vermeer's daughter. Much more to it than I remembered, and of course plenty of controversy too:

https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2009/jul/12/g…

My reaction to Vermeer's painting has always been much different than yours. I see a bright-eyed, curious young woman, not a "dimwitted" person. I often reflect on how different standards of beauty have become, mostly because of her protuberant eyes, which in these days of air-brushed models do not fit commercial standards of attractiveness. This leads me to think about how much more varied the faces of Vermeer's time might have been, with more scarring, no orthodontia, more exposure to the elements, and so on. I think how fortunate the young woman is to have lovely skin.

When I look at her mouth, I don't see an open mouth, although I do see parted lips. This seems normal to me, as my lips are parted most of the time. When my mouth is closed or my lips pressed together, I look unhappy at best, and often severe or grim. The unflattering contemporary term for this is "resting bitch face," or RBF. It may be that the girl naturally keeps her lips parted some of the time, that parting them was part of the painter's instruction to the sitter, that the portrait is of someone looking to the side and parting her lips in surprise, or that there is some other reason lost to us. Her mouth does not look slack or droopy to me, nor does her affect look lax, which I would associate with disinterest, dimwittedness, or intellectual handicaps.

Interestingly, I don't speculate about the social status of the woman wearing the earring, although occasionally I wonder if she was old enough to be in the first few months of pregnancy. She seems luminous, serene, and secure, even though by my standards life in her time was difficult and precarious, especially for women facing childbirth.

For me, the bust of Nefertiti is elegantly beautiful but distancing in its formality. She does fit the almost unattainable standards of commercial art photo illustrations in our time. I rarely think of the person she might have been when I view photos of her face. The Vermeer portrait keeps my interest longer. I wish you could see the Vermeer through my eyes, with my mixed experience of measuring up and (most often) not measuring up to standards of beauty in the mass media.

I am, as always, a day (or a week and change) late and a dollar short, but I was glad to see Editor 308's response. Since reading the original post, I've been revisiting the painting, as well as one can via the internet, and, from that limited vantage point, what I'm seeing is something like the famous drawings that are simultaneously a rabbit and a duck, an old woman or a young one, a vase or the silhouettes of two people facing each other. I can, with Mr. Wimberly's post in mind, easily see the features associated with dim-wittedness, but I can upon another viewing see precisely what Editor 308 sees. I would add that coming (as we all do) from a context in which photos-and even carefully constructed portraits-show their subjects (as if) turning from something else to look at the viewer, often with an expression of surprise or pleasure on their faces. In that case, I interpret her parted lips as indicating that she's about to speak.

I wanted to comment, if for no other reason than to express my appreciation for having the Vermeer drawn to my attention. I've seen it hundreds of times, one way or another-and never really focused on it. (I have not, however, seen it "in person." If anyone would care to spot me a plane ticket, I could use a break. Just saying. Although perhaps not: my grandfather entered the country with papers that were, shall we say, not entirely "in order," and the way ICE is going, I might not make it back in.)

With Nefertiti, while recognizing that to us she is stunningly beautiful, I cannot help but wonder about the degree to which she would or would not have been considered iconically beautiful in her original context. Her neck is strangely long, and she appears very thin. Her features are regular, but they are different from the stylized features we see on most of the sculptures of the periods before and after Akhenaten's reign, and I'm inclined to think the stylized forms represent the standards of beauty of the time and place.

I am, as always, a day (or a week and change) late and a dollar short, but I was glad to see Editor 308's response. Since reading the original post, I've been revisiting the painting, as well as one can via the internet, and, from that limited vantage point, what I'm seeing is something like the famous drawings that are simultaneously a rabbit and a duck, an old woman or a young one, a vase or the silhouettes of two people facing each other. I can, with Mr. Wimberly's post in mind, easily see the features associated with dim-wittedness, but I can upon another viewing see precisely what Editor 308 sees. I would add that coming (as we all do) from a context in which photos-and even carefully constructed portraits-show their subjects (as if) turning from something else to look at the viewer, often with an expression of surprise or pleasure on their faces, it is easy to interpret her parted lips as indicating that she's about to speak and her facial expression as a slight smile.

I wanted to comment, if for no other reason than to express my appreciation for having the Vermeer drawn to my attention. I've seen it hundreds of times, one way or another-and never really focused on it. (I have not, however, seen it "in person." If anyone would care to spot me a plane ticket, I could use a break. Just saying. Although perhaps not: my grandfather entered the country with papers that were, shall we say, not entirely "in order," and the way ICE is going, I might not make it back in.)

With Nefertiti, while recognizing that to us she is stunningly beautiful, I cannot help but wonder about the degree to which she would or would not have been considered iconically beautiful in her original context. Her neck is strangely long, and she appears very thin. Her features are regular, but they are different from the stylized features we see on most of the sculptures of the periods before and after Akhenaten's reign, and I'm inclined to think the stylized forms represent the standards of beauty of the time and place.