As noted by the Senior Editor of the Oxford English Dictionary, there’s been some consternation recently about the inclusion of a figurative interpretation of ‘literally’ to the list of acceptable definitions of the word.

What may surprise [people] is to find that th[e figurative] usage is much older than you would think. While it is true that it has become increasingly common in modern usage, it was actually first included in the OED in 1903. When the entry was updated and published online in September 2011, we found even earlier examples of this usage – our earliest example is currently from 1769…

I’m no lexicographer, nor am I a philologist by any stretch of the imagination. My knowledge of the terms ‘prescriptivist’ and ‘descriptivist’ just about exhausts my familiarity with the field.

Simon Winchester’s history of the OED did, however, make me think that inclusion of the figurative interpretation of ‘literally’ may in fact have been well overdue. If you haven’t read it, I encourage you to squeeze it in as (perhaps your final) summer read.* I won’t regurgitate the history, as much of the material can be found in condensed form at Wikipedia, or in far more entertaining and engaging form from the book itself. I’ll draw attention to just one aspect of the story: the Dictionary project emerged after a series of lectures that were delivered to the newly formed Philological Society convinced its members of the inadequacy of previous efforts (notable examples including Dr. Johnson’s). If the task was to succeed, the lectures argued, the English Dictionary would need to jettison the approach of having a committee decide on the correct usage of words by central diktat. While such an approach might have worked for languages like French or Italian, for which the rules and vocabulary were more rigid, the “mongrel†nature of English required a different approach altogether. Instead, an English Dictionary necessitated soliciting English speakers for suggestions of how words have been used, rather than how they ought to be used.

The Philological Society lectures argued that because English is such a mish-mash of different rules and practices, any lexicographer assembling an English dictionary would be forced to apply only the very lightest touch in providing guidance. Indeed, this is reflected in Ms. McPherson’s post. Back to her:

Whatever the reasons, it is clear that people often have strong opinions about “new†senses of words. Perhaps the question is not so much why do people have a problem with literally but rather why do lexicographers not have a problem? It comes down to that oft-spoke mantra – language changes. Our job is to document that for better or for worse. Except for us, there is no worse. We have to look at language objectively and dispassionately. Of course, part of our job is to give guidance on what might be acceptable when. That is why we label some words as slang and why we give a usage note at the offending sense of literally, making clear that although it is very common, it is considered irregular in standard English.

We’ve known for a long time what is meant when someone says “I literally can’t take any more.” It’s perfectly regular and comprehensible, and objection to its use is really just the same kind of snobbery as quibbling over whether ‘data’ is singular or plural. The answer: yes, technically, ‘data’ is a plural word, but if you want to treat it as such, you’re probably being a hypocrite in the way you use many other words. So you’re best off just sticking with what comes naturally (i.e., the singular). Moreover, as McPherson notes, the greatest harm (if any) is that a figurative use of ‘literally’ is pleonastic. All of this is just another way of saying that language use in English generally resorts to conventions rather than rules set out by lexicographers. The originators of the OED at the Philological Society have been vindicated, it seems.

In addition to being one of the most impressive and inspiring projects of which I know, the OED also strikes me as a model for one of the first ‘open-source’ data collection projects. With its practise of soliciting input on word usage from word users throughout the world, I wonder how much precedent can be found in the history of the OED in the formation of Wikipedia.

*By which I mean Winchester’s book. Then again, if you want to read the OED, …I suppose some people do that for fun.

Of course, “literally” has been replaced by “like.” Like, “I was like blown away.”

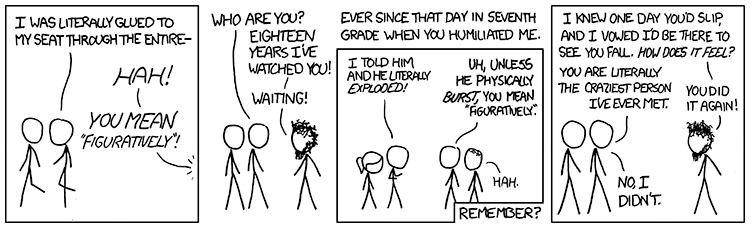

Has Randall Munroe yet made an xkcd about how there’s an kcd for every purpose?

Oh come on, the use of data as a singular noun is radically different than the use of literally as an all-purpose intensifier. When people use data as a singular noun, for example, to say “the data disproves the hypothesis”, they are actually using the correct verb form, because it is almost always not the case that each individual data point proves or disproves a given hypothesis. It is almost always the case that the collection of data points proves or disproves something. So, yes, the correct usage of “data” is as a collective noun that’s treated as a single entity, and treating it as a plural noun is making an argument which can’t be supported.

But using literally as a general, all-purpose intensifier is a case in which you are using the word in a meaning which is the exact opposite of the other meaning. This is just a bad idea. There are other words or phrases that you can use instead, so why shanghai that particular word into this usage?

You mean, “making an argument THAT can’t be supported.” 🙂

Good point about “data.” I’d never thought of that. I will make explicit what I think you imply when you say “WHEN people use data as a singular noun.” There are occasions when it does take a plural verb, such as “Where are the data?” “The data are on the desk.”

Crap, I always screw up the that/which distinction.

And when I say “always”, I mean literally always.

And when I say “literally”, I mean I don’t really know what words mean.

that/which is actually easy (like Miss Manners’ fork rule: use the (remaining) one furthest to the left):

Use neither if you can “the book I lent John”

Use that if it sounds OK “the book that explains that/which”.

Use which if neither of the above works “the book, which weighs four pounds, is called the Shorter OED.”

Even easier: if a comma is necessary before which/that, then it’s “which”; otherwise it’s “that.” This is because the phrase beginning with “which” (such as “which weighs four pounds”) could be dropped and the sentence would remain intact (“the book is called the Shorter OED”). Dropping a phrase beginning with “that” would render the sentence meaningless (“the book that explains [explains what?]”).

“Use neither if you can” concerns a different matter. But the AP Stylebook suggests erring on the side of inclusion.

The other occasions I can think of with data taking a plural verb are sentences like “The data were taken at room temperature and at atmospheric pressure.” But even then, most people would use “measurements” or “data points”. I get the impression that the contemporary usage of the word “data” almost always refers to multiple objects taken as a singular entity.

How bout the good old fashion singular - datum - instead of that awkward term - data point(s)? As in, “the case that each individual [datum] proves” or “that the collection of datum proves or disproves something.” Just saying!

It may be awkward, but for the most part, it seems to be used more often than “datum”. But hey, if anyone at work or a referee of a publication told me to use “datum” instead of “data point”, I’d do it without a second thought.

And to the extent that usage moves in ways that are a bit annoying or awkward, I can roll with it. But when an alternate meaning which is the complete opposite of an existing meaning is mainstreamed, it’s much more problematic.

There are plenty of instances in which a word has two opposite meanings. Off the top of my head, while this example is imperfect, the verb to “table” an issue can mean either to address it immediately or to postpone discussion of it until another time (although in this instance the different meanings are attributable to conventions held on either side of the Atlantic — given time I have a feeling a better example would spring to mind).

Why shanghai that particular word into this usage?

Well, you’ve identified it yourself: it’s an all-purpose intensifier. When we’re dealing with a figure of speech (as in “I literally died laughing”), the word ‘literally’ doesn’t obfuscate the sentence’s meaning at all. By using ‘literally’, we’re inviting an interlocutor to visualise the figure of speech with more attention, and perhaps with more vividness, than usually is the case. “Using another word” as you suggest would constrain us to signalling to our interlocutor that all we’re conjuring is a figure of speech, and nothing more. The simulacrum of realness introduced by the word ‘literally’ provides the desired emphasis. Hence its effect, and my support of its inclusion in the OED.

Yes, in the case of “I literally died laughing”, we know that the speaker didn’t actually die. How about, “Me and Dave got high on a bunch of horse tranquilizers, then Dave started doing his impression of Estelle Getty in The Golden Girls. I was laughing so hard, I literally shat my pants”? Is that vivid or is the speaker being annoying? I vote annoying.

You can point to other words which have the unfortunate distinction of having two opposite meanings. And “table” is one of those where both meanings are so well-entrenched that it’d be nearly impossible to convince people to only use one of the two. Despite the fact that “literally” has had people misusing it for more than 2 centuries, there have been people pushing back against the pointless use of it as an all-purpose intensifier. And now the OED has decided to throw its hands up and say “Oh, screw it. We give up.”

You’re more than okay with that. And should people decide to revive the older, disused meanings of common words like “neat” without explaining what they’re doing, I’m sure a whole lot of people will spend a lot of time being annoyed at reverse-pedantic etymological archeologists.

Whoops, that should be “that have the unfortunate distinction”. See, I literally always do that.

🙂

In the example you’ve provided, the implication is that this is a funny story. My inability to discern which of the meanings (whether figurative or not) is precisely what you’re playing on to get me to laugh. In this case, the lack of clarity is the source of the humour.

The OED hasn’t “thrown its hands up”. Part of my post was intended to correct the mistaken assumption that the OED was ever really designed to arbitrate between which usage was ‘the correct’ one in the first place. It’s much more of a follower than a leader.

Yes, that example was a paraphrase of a David Cross bit. But the confusion caused by the intensifier use of “literally” is a lot more common that you think, and on top of that, I can’t imagine a single usage of “literally” as an intensifier that really works that well even when it is clear that they aren’t using “literally” to mean, well, “literally” instead of “super awesome totally intensely!”.

Then, on top of that, the intensifier use of “literally” simply creates the same problem at a once remove. We now need a word that means what “literally” should mean, because people will use the word non-ironically as an intensifier and we’ll need a word that restores clarity in confusing situations, where someone might actually, really, literally, physically void their bowels into their pants from laughter. What should that word be? And what happens when people decide to use that word as an intensifier?

The speaker who would say, “I figuratively shat my pants” would be the most annoying of all.

But it’s not the exact opposite.

is not the same as

or (less awkwardly)

(or even less awkwardly, when the intent is clear)

As you pointed out, in

the word “literally” acts as an intensifier, while in

there is no intensifier.

Sure, there are other words that can be used, but language always gives us different ways to express ourselves.

Sometimes using “literally” as an intensifier can lead to confusion, but sometimes using “literally” the way Anonymous37 thinks you’re supposed to can cause confusion.

Yes, if everyone in a given conversation is on the same page that using “literally” as a general, all-purpose intensifier is a pointless and irritating affectation that should be avoided at all costs and then someone in that conversation claims that something is “literally” true (here, we’re using the correct use of “literally”) that in reality makes no sense, then sure, confusion will result.

That confusion, of course, has nothing whatsoever to do with the use of “literally”. People can lie with sentences which use the word “literally”. People can misunderstand the definitions of terms in sentences that use the word “literally”. People can use it sarcastically to make fun of people who use the word as a useless intensifier. (I am perfectly okay with that last one.)

And that’s what your example above is about. That example is someone claiming that 20 or 30 is literally, actually, mathematically “hundreds”. Or who is being sarcastic by mocking the other person for making a claim that is hugely improbable. Yes, confusion can exist in conversations where people use the word “literally”. That same confusion will exist in the version of the conversation which eschews the word “literally”. But in cases when people aren’t making improbable claims or being sarcastic, the correct usage of “literally” will help get people on the same page.

I’ve come around to one of Johann Koehler’s arguments; the OED should note the other usage of “literally” in order to warn the unwary that people might actually mean “not literally” when they say or write “literally”. And as much as I’d like them to, it isn’t appropriate for them to editorialize when noting that second definition.

And let’s take your other example of “The President literally threw the cabinet secretary under the bus” versus “The President threw the cabinet secretary under the bus”. Thank you for making my point for me; using the word “literally” adds absolutely nothing to the meaning of the sentence. For one thing, that metaphor isn’t really amenable to intensifiers; and for another, if someone felt the need for intensifiers to that sentence, it should be explanatory, like “The President threw the cabinet secretary under the bus. It’s the worst betrayal of an underling by an American president since Reagan’s treatment of Stockman.” Unless the President actually and physically picked up and threw one of his cabinet secretaries under a bus, then using “literally” in that sentence is pointless.

So yes, in fact, “The President literally threw the cabinet secretary under the bus” means (when “literally” is being misused) pretty much exactly the same thing as “The President figuratively threw the cabinet secretary under the bus”. With one important difference: the sentence “The President figuratively threw the cabinet secretary under the bus” has the virtue of making it clear to the reader that the extremely improbable event of the President killing one of his or her cabinet secretaries with a bus has not occurred.

I just realized an exception to what I said above. You shouldn’t use the word “literally” sarcastically to make fun of children and people whose first language isn’t English who misuse the word. There are limits.

I can’t think of a case where literally as a mere intensifier really adds anything to metaphoric speech. Absolutely might be the somewhat better substitute Anonymous37 is looking for. But “I died laughing when Perry literally couldn’t remember his third agency” is actually no less effective or intense than “I literally died…” Why not just omit it in this vacuous usage?

As always, Munroe saves his best punch-line for the mouse-over text: The chemistry experiment had me figuratively — and then shortly thereafter literally — glued to my seat.

An interesting Slate article by a dictionary editor on the topic. I recommend it to anybody interested in the topic, but I’ll quote briefly from it here.

First of all, some of our best authors make the same “mistake”:

Do any of these work better without the literally? These masterful stylists seem to think that they don’t.

And why is “literally” under attack when there are other words that work the same way but aren’t under criticism?

Since you ask, yes, the example from Fitzgerald works better — much, much better — without “literally”. The example from Twain is slightly murkier, as I can easily imagine him using a word colloquially in order to affect a folksy voice. Joyce’s usage could be acceptable, if he’s making a point that Mozart actually isn’t as great as others think he is, and he’s subtly undermining the apparent meaning of the sentence by misusing the word “literally”.

And I have no problem with authors including words in dialogue in ways that people would use or misuse them in real life. If Alcott wants to have Meg use the word “really” in that sentence, that’s completely fine. And the example from Joyce’s Ulysses may well fall into this category, too.

Outstanding blog, good looking roughly some blogs, seems a euphonious charming dais you are using. I’m currently using WordPress for a occasional of my sites but looking to change joined of them outstanding to a stage similar to yours as a trial run. Anything in picky detail you would make attractive thither it?

レディースナイキフリー5.0 V2 http://www.nikefreejapanrun.com/レディースナイキフリー50-V2-c-3_18/