Martin and John Michael McDonagh have earned an estimable reputation for themselves in Hollywood with their offbeat character studies that traverse action, comedy, and drama. Although I have already praised The Guard at RBC, most will be familiar with the work of the younger brother, Martin McDonagh, for In Bruges. This week’s film recommendation is Martin’s most recent feature film, which moves the setting from Europe to Los Angeles, in Seven Psychopaths (2012).

The self-referential hook in the film’s plot is easy to spot. Marty, played by Colin Farrell, is an Irish scriptwriter laboring with a drinking problem (some of the clichés are too obvious to be unintentional) and nothing more than a great working title—“Seven Psychopathsâ€â€”for his long overdue next work. Marty’s rare progress on the script relies on infrequent moments of sobriety and inspiration offered by his eccentric friend Billy, played by Sam Rockwell.

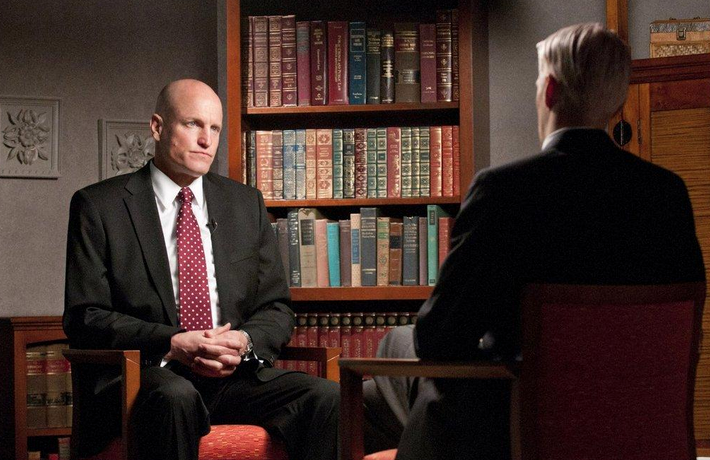

Billy’s daytime job is a collaborative effort with Hans, played by Christopher Walken, to kidnap wealthy Angelenos’ dogs only to return them in exchange for a hefty payout. Things take a turn for the unexpected when they happen to kidnap a dog that belongs to Charlie, one of LA’s crime bosses played by Woody Harrelson. Charlie’s love of his dog is so profound that the lengths to which he’ll go to retrieve it are unquestionably psychopathic.

You’d have to be witless to be surprised by the film’s big reveal, which happens about two-thirds into the film. The stories that Billy has been feeding Marty to enable progress on the script are drawn from characters he himself encounters. Sometimes the script merely reflects what Marty has witnessed, whereas sometimes Marty has reproduced an incriminating story recited to him by Billy.

But where Seven Psychopaths really gets going is in those moments when McDonagh plays around with the meta trope to the point that Marty’s stories presage events before they even unfold around him. Is this a drunken hallucination? Is Marty a supernatural being, capable of commanding events into existence with his pen? Is the world nothing more than a representation of Marty’s own grandiose self-image borne out of psychopathy of his own?

McDonagh is perfectly capable of creating a fun and watchable crime caper, but his real strength is in playing with an audience’s expectations about the genre’s form itself. He seems to delight in ridiculing the pomposity of most action films and the over-blown macho types who typically populate them. Hence his selection of a bunch of pathetic characters to appear as his eponymous psychopaths, who fumble around desperately searching for a purpose worthy of their inflated attention-seeking egos. No such luck, unfortunately – they have to make do with the hand they’re dealt: a crime boss’ pathological inability to hold back tears at the thought of his stolen shih tzu; a pitiful excuse for a final shootout; and a wacky bartender’s effete attachment to a bunny. It’s all there to rescue the audience from having to watch yet another movie that exhausts further the already drab and tired tropes common to the genre.

Like a few films I’ve reviewed at RBC that toy with the film-making conceit (e.g., see 20,000 Days on Earth or Rubber, among others), the self-referential theme running throughout the film gives the impression that there are a few hidden jokes that aren’t intended for the audience –perhaps McDonagh is guilty of making a few jokes for his own amusement. This would be consistent with the self-obsession of the characters on screen. I certainly wasn’t inclined to begrudge him that much with a film as plainly entertaining as was Seven Psychopaths.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OOsd5d8IVoA