A bad week in democratic politics. By the virtual filibuster procedure conceded by Harry Reid, the Republican minority in the US Senate killed the minimal Manchin-Toomey bill ever so slightly tightening background checks on gun sales. It almost adopted Cornyn’s amendment imposing interstate recognition for concealed carry, a step toward the gun nut dystopia of arms everywhere, all the time.

American politicians are crazy, I thought, European ones are just stupid, I thought. Until the European Parliament voted down the Commission’s proposal to tighten carbon emissions allowances and revive the cap-and-trade market, now at a zero lower bound that makes the scheme a nonsense.

At least the American public, if it’s interested, can find out instantly who crashed the plane. I can’t find a proper analysis of the EP vote. Here is the raw voting list by parties (doc, page 23, vote on item 10, amendment 20 to reject the proposal). List of political groups, to explain the acronyms. Debate transcript - not yet translated, so you get the multilingual flavour of the plenary, if not a full understanding, unless you read Greek and Finnish.

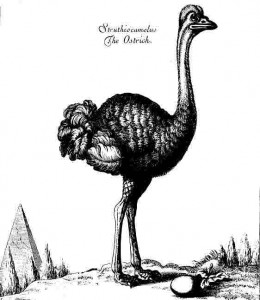

In an engagingly eccentric BBC programme on 17th century sensibilities, they picked Sir Thomas Browne, provincial doctor, polymath, writer of prose as rich and flavourful as Malmsey, and enthusiastic but unstructured Baconian experimenter. His best-selling(!) compendium of received errors, Pseudodoxia Epidemica: or, Enquiries into very many received Tenents and commonly presumed Truths (1646), has a chapter attacking the belief that ostriches eat iron.

In an engagingly eccentric BBC programme on 17th century sensibilities, they picked Sir Thomas Browne, provincial doctor, polymath, writer of prose as rich and flavourful as Malmsey, and enthusiastic but unstructured Baconian experimenter. His best-selling(!) compendium of received errors, Pseudodoxia Epidemica: or, Enquiries into very many received Tenents and commonly presumed Truths (1646), has a chapter attacking the belief that ostriches eat iron.

The ground of this conceit is its swallowing down fragments of Iron, which men observing, by a froward illation, have therefore conceived it digesteth them; which is an inference not to be admitted, as being a fallacy of the consequent, that is, concluding a position of the consequent, from the position of the antecedent. For many things are swallowed by animals, rather for condiment, gust or medicament, then any substantial nutriment. So Poultrey, and especially the Turkey, do of themselves take down stones; and we have found at one time in the gizzard of a Turkey no less then seven hundred.

Browne finally encountered a live ostrich. According to Leslie Stephens [microupdate, see comments]:

Sir Thomas takes a keen interest in the fate of an unlucky ‘oestridge’ which found its way to London in 1681, and was doomed to illustrate some of the vulgar errors. The poor bird was induced to swallow a piece of iron weighing two and a-half ounces, which, strange to say, it could not digest. It soon afterwards died ‘of a soden,’ either from the severity of the weather or from the peculiar nature of its diet.

The BBC presenter Adam Nicolson claims, relying on Browne’s copious notebooks, that he first tried to tempt the ostrich by concealing the iron in a pastry, like a haematic pain au chocolat. (Browne’s style is catching.) The ostrich ate the bun, but spurned the filling.

The BBC presenter Adam Nicolson claims, relying on Browne’s copious notebooks, that he first tried to tempt the ostrich by concealing the iron in a pastry, like a haematic pain au chocolat. (Browne’s style is catching.) The ostrich ate the bun, but spurned the filling.

By what illation do we get our ostrich politicians to swallow their iron bun?