Originally trained as a visual designer, Satyajit Ray is regarded in Indian cinema history as one of its greatest directors, and as the auteur responsible for creating the first domestic film to acquire success abroad. That film, which is the first of both Ray’s career and of a trilogy named after its protagonist “Apu,” is Pather Panchali [Song of the Little Road] (1955).

While the sequels deal with Apu’s life as an adolescent and then as a young adult, Pather Panchali centers on Apu’s birth and early childhood. Born to a penurious family in rural Bengal, the father Harihar (played by Kanu Banerjee) is a scholar, poet, and priest who is perennially trying to scrounge together some money to repair the family home, feed the children (Apu is accompanied by an older sister named Durga, played exquisitely by Uma Dasgupta), and purchase new clothes for his wife Sarbajaya.

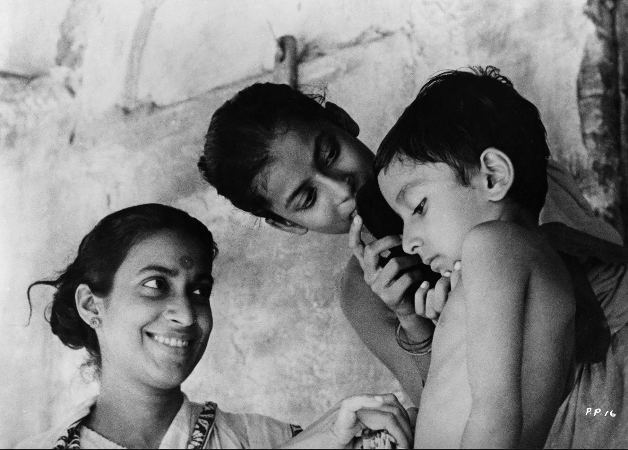

Although the trilogy is named after Apu and follows his life over multiple decades, it is his mother Sarbajaya, played by Karuna Banerjee, who is really the focal point for Pather Panchali. At the beginning of the film, she is the proud guardian of the homestead, delegating responsibilities and keeping the children fed. Even though she is understandably hurt when she overhears her neighbors gossiping unflatteringly about her parenting, Sarbajaya is a composed and dignified woman. As the story progresses, however, and the family’s poverty deepens, it’s through her quiet frustrations and increasingly exasperated efforts to pawn belongings that we notice the growing intensity of the family’s despair, and the gradual weakening of the formidable determination she showed when we first met her. Apu’s upbringing is thus told through his relationship with his mother, who—although always loving— is over-bearing, stern, and disciplinary.

Sarbajaya’s efforts to keep Apu on the straight and narrow are repeatedly flummoxed by Harihar’s cousin, the elderly Indir (played by Chunibala Devi). To Sarbajaya, Indir is a complete pest: she encourages the children to misbehave, she completely over-stays her welcome, and she has an unsettling fondness for morbid folk-tunes that enervate Sarbajaya’s spirits. All the same, Indir has an unusual charm. Her meditations on death and life border on insincere attention-seeking, but in her absence the other characters learn that Indir has the most to teach.

Apu’s outlet for childish mischief is his relationship with his older sister Durga, who shares with Apu her curiosity about the daily locomotive that passes near their home. Ray’s fawning representation of the train and the associated industrialization of India synchronized with Nehru’s platform of non-alignment, as Pather Panchali evokes a welcoming of new-ness and a readiness to participate in the new world of industrial advance and technological progress. The congruity between Ray’s thematic delivery and Nehru’s political agenda secured not only the funds necessary to complete filming, courtesy of the West Bengal government, but it also earned Nehru’s endorsement when Ray took the film abroad to Cannes.

Rather than assigning a leitmotif to each character, Ravi Shankar’s soundtrack assigns a classical raga that corresponds to each emotion or impression conveyed over the course of the film. The music sometimes follows the mood of the film, and at other times it leads the audience’s impression. The pace obeys none of the forms that modern movie-going audiences have come to expect, and so some may find the film slow and even possibly tedious, especially during the first half. But Pather Panchali rewards patience, as the story gathers weight and Ray’s vision becomes clear.

Rather than post a trailer, here’s a clip of Apu and Durga playing in the rain that gives a flavor of the film’s mood.