…And before it’s operationally relevant. After all, it’s a part of human life. With any luck, they’ll be less screwed up than their parents were.

Tag: public health

Driving and cell phones

I was listening to WEEI’s broadcast of the ball game in the car this evening (the game in which Boston clinched a playoff slot, woo hoo). It’s a wonderful world in which I can set my smartphone - better called a pocket computer - to pick up a Boston radio station from the web, a continent away, and plug it into the Aux input of the car radio,.

The announcers interviewed a honcha of AT&T’s New England operation during a pitching change, about a PR program AT&T is putting on to discourage texting and driving. Good for AT&T, but she made a serious mistake, plugging a speech-to-text/text-to-speech technology for texting. Do. Not. Do. This. And do not use a hands-free device to talk on the phone in the car; it’s just as dangerous as holding the phone up to your ear and talking.  Think about all the great RBC posts you will miss if you are dead. David Strayer at the University of Utah runs the go-to lab about this and in their latest very interesting paper we find

Taken together, the data demonstrate that conversing on a cell phone impaired driving performance and that the distracting effects of cell-phone conversations were equivalent for hand-held and hands-free devices….Finally, the accident data indicated that there were significantly [p<.05] more accidents when participants were conversing on a cell phone than in the single-task baseline or alcohol [BAL = .08] conditions.

Why this is true is not intuitively obvious, and I think even Strayer’s group, who recognize that this is a cognitive problem and not an issue of visual distraction by the keyboard, doesn’t quite get it: the psychology through which the cell phone impairs driving is not only the driver’s but also the conversational partner’s, and what the driver intuits about the latter. Continue reading “Driving and cell phones”

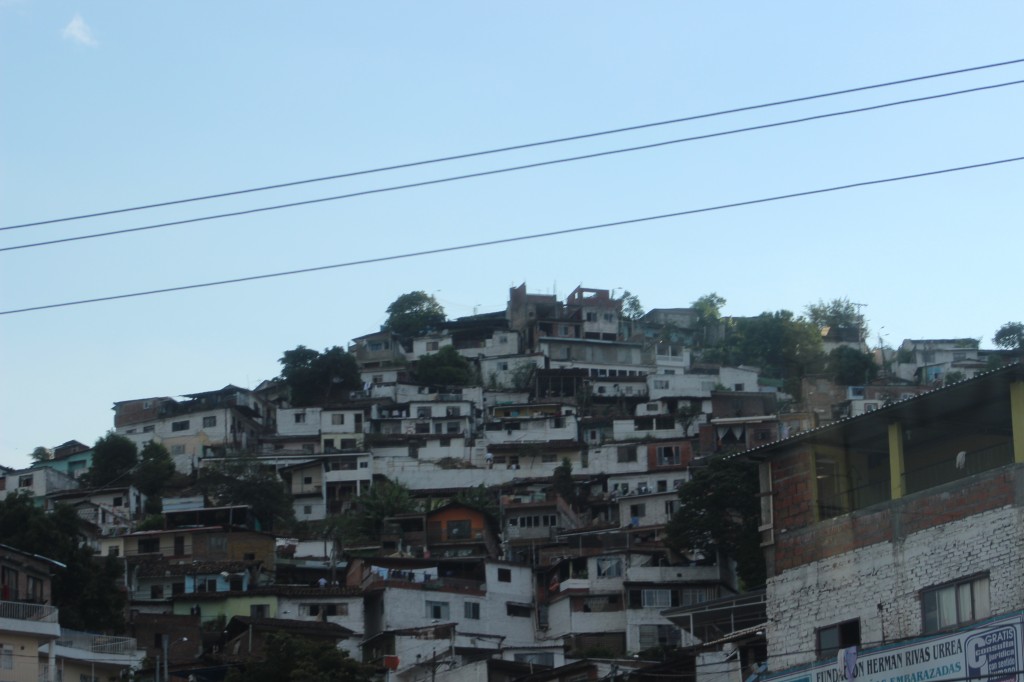

“They could have killed me very easily,” my conversation with the Mayor of Cali, Colombia

If Zeke and Rahm Emanuel could combine in a single man, it would be Rodrigo Guerrero Velasco, mayor of Cali, Colombia. He is an elected member of the Institute of Medicine, and a PhD in epidemiology from Harvard. He’s played an important role in reducing homicides in Cali, despite that city’s incredible challenges from the cocaine cartel and other sources. (Progress is relative. Cali’s homicide rate remains four times Chicago’s rate.)

We had a wide-ranging conversation about youth homicide prevention, gun and alcohol curfews, and other matters. More here, at the Washington Post‘s Wonkblog section.

Margaret Thatcher: harm reduction heroine

Cross-posted with TCF.org….

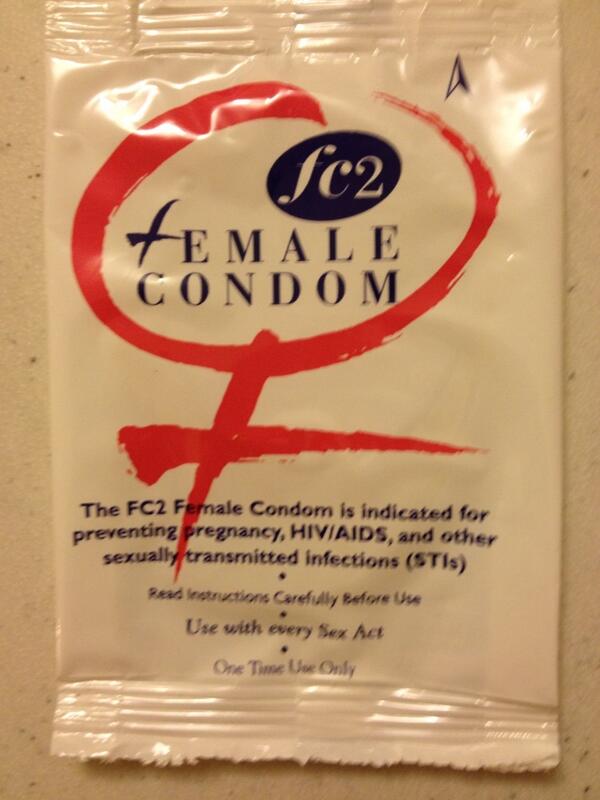

I’ve been following my left-liberal friends’ reaction to Margaret Thatcher’s death. I take it they’re not huge fans of her historical legacy. I’m not such a big fan myself. But one aspect of her legacy deserves some notice. The Thatcher government responded rather effectively and humanely to the HIV/AIDS crisis. Embracing harm reduction measures such as syringe exchange and methadone maintenance, it saved thousands of lives. Indeed the words “harm reduction,†anathema to American drug control policy until the Obama administration, were official watchwords of British drug policy. As Alex Wodak and Leah McLeod summarize this history:

By 1986 the Scottish Home and Health Department concluded that ‘the gravity of the problem is such that on balance the containment of the spread of the virus is a higher priority in management than the prevention of drug misuse.’ and recommended accordingly that ‘on balance, the prevention of spread should take priority over any perceived risk of increased drug use.’ This approach was strengthened by the influential UK Advisory Committee on the Misuse of Drugs asserting in 1988 that ‘the spread of HIV is a greater danger to individual and public health than drug misuse…accordingly, services that aim to minimize HIV risk behaviour by all available means should take precedence in development plans.’

Thatcher-era British policies provided a damning contrast to the Reagan and George H. W. Bush administrations, which so disfigured their legacies by allowing HIV policy to become yet another front in the culture wars. More than 600,000 Americans have died after being diagnosed with AIDS. An unknowable number of these deaths would not have occurred had our government moved with greater speed, resources, and humanity to contain a deadly epidemic.

The HIV epidemic struck at the weakest points of American society and our political life. The centrality of homosexuality and drug use guaranteed that HIV prevention would spark bitter ideological and moral fights. Within the British system, these fights occurred in a context in which experts at the National Health Service and related public health bodies commanded real legitimacy and respect within the political process.

Things played out rather differently here. In September 1985, President Reagan prepared to make his first, very-late public comments on AIDS. Responding to unfounded fears, health authorities proposed to include the following words in his speech: “As far as our best scientists have been able to determine, AIDS virus is not spread through casual or routine contact.â€

These words were never spoken. A young White House aide redacted them. This story is telling, not because that young aide—now Chief Justice of the United States—got the science wrong. It’s telling because the medical and public health consensus was casually over-ruled by a young lawyer who knew little about AIDS. Public policy is not only about making the right decision. It is also about creating the right organizational capacities and the right norms of decision-making so that judicious analysis is performed and is then given a proper hearing. That didn’t happen.

The Reagan presidency ended twenty-five years ago. That was a different time. Public attitudes have changed—not least because of what we all witnessed in the HIV epidemic itself. Maybe it’s unfair to judge American public policy of the 1980s by our values three decades later.

Still, it’s still worth remembering that one of the English-speaking world’s greatest conservative politicians faced the same crisis, at the same moment, just across the Pond. And the Iron Lady did much better.

What are people inhaling when they advocate policies not to hire smokers?

I’m just dumbfounded that distinguished medical professionals would support such a policy.

I am an emphatic tobacco control advocate. My mother-in-law and my father-in-law both died horribly and young of lung cancer. I yield to no one in my desire to tax the hell out of cigarettes, require aggressive warning labels, the full list. I despise the tobacco industry, and would stop just-short of TP’ing Altria’s corporate headquarters.

I remain dumbfounded that distinguished medical professionals would countenance a policy of refusing to hire smokers. Of course, people shouldn’t smoke. I have no problem with any number of workplace smoking restrictions, particularly in medical settings.

Yet the proper goal of tobacco policy is embrace and help smokers, not to bully them or discriminate against them. Such employment policies are appallingly unfair and discriminatory. I also believe such policies are unethical, particularly when one considers the reality that tobacco use is increasingly concentrated among low-income and less-educated Americans whose economic and political influence is nowhere near what it used to be.

Mayor Bloomberg seems to have overstepped public opinion with his efforts to limit large serving-sizes of sugary drinks. Maybe so, but attacking the Big Gulps seems a much-less disturbing intrusion of the nanny state than a policy which would deny employment to otherwise-qualified smokers.

I’m not sure what people are smoking who advocate such discriminatory policies. They should smoke something else.

Community Reinvestment Comes to Health Care

I have no idea what the nonprofit community would do without Rick Cohen of the Nonprofit Quarterly: if there’s an issue affecting nonprofits he’ll have a fresh and useful perspective on it, and this article about the Community Health Needs Assessments required by the Affordable Care Act is no exception.

What struck me most was Cohen’s point that CHNAs could do for health care what the Community Reinvestment Act did for real estate lending: make large institutions pay attention to the communities where they do business. Whatever its weaknesses, CRA did make a serious dent in the once-common practice of red-lining, refusal to lend in poor neighborhoods, and we can expect CHNAs to make a similar change in the culture of nonprofit hospitals. Simply providing an emergency room isn’t sufficient community service, and if a nonprofit hospital fails to grasp that it jeopardizes not only its Federal health-care dollars but the tax-favored status of the rest of its income.  We know that because the provision calls for enforcement by the IRS as well as the Department of Health and Human Services.

This sort of positive pressure from the legislature to improve community health services is far more effective than the purely negative pressure courts can supply by rejecting a hospital’s claim of charitable status (as in the Provena case in Illinois). Because the point isn’t to play “gotcha” with nonprofit hospitals—it’s to supply communities with the maximum benefit possible from the health care resources already available.

Once again the more you know about the Affordable Care Act, the better you like it.  And “Obamacare,” intended as an epithet, sounds more and more like a well-deserved tribute.

cross-posted with The Nonprofiteer: www.nonprofiteer.net

Open carry makes you safe

Two people out having fun with their friends were murdered yesterday in Texas because their rights, and their friends’ rights, to openly carry adequate firepower have been savaged. If good guys with guns, trained in using them, had been visibly on the scene, this never would have happened, right?

Two steps forward, one step back fighting HIV in Chicago

Last week, one of my twitter followers called me to task for writing an entire column on HIV and AIDS without focusing on the huge disparities by race/ethnicity. She was certainly correct about the critical role of such disparities. Yesterday-again on twitter-Chicago commissioner of public health Bechara Choucair drew my attention to an especially pertinent report on such matters.

Little by little, Chicago is making progress in addressing rising HIV incidence, non-diagnosis, and late treatment among young men who have sex with men. Thing’s aren’t great, or even remotely acceptable. Epidemiological data from the Chicago component of the National HIV Behavioral Surveillance (NHBS) System indicate that HIV prevalence among men who have sex with men (MSM) continues to rise. At least a higher proportion of men know their status and are getting treatment.

In 2008, 67% of surveyed (and tested) Black MSM found to be HIV-positive were not aware of their infection. By 2011, only 33% were similarly unaware. These numbers remain far too high. (The comparable figures among non-Hispanic White MSM were 23% and 9% in the same years.) Yet awareness is moving in the right direction. MSM who tested positive in 2011 were also more likely to be receiving appropriate medications than was found in 2008. Among African-Americans, the percentage of HIV-positive MSM reporting being on HIV medications increased from 44 to 84 percent. Among HIV-positive Hispanic MSM, there was a similarly large increase from 50 to 82 percent. (Again-among surveyed non-Hispanic white MSM, the comparable figures were, um, 90 and 100 percent.) These data are hardly airtight; epidemiological data concerning stigmatized behaviors seldom are. The basic story here seems consistent with other sources.

If you are still wondering why there is such urgency concerning African-American MSM, read the accompanying report. In particular, compare the top two lines from Figure 2 (below the fold). Both the level and the disparity remain really concerning. So any sign of progress is especially heartening. Continue reading “Two steps forward, one step back fighting HIV in Chicago”

The external cost of guns v. smoking

A quick post on the cost of smoking v. cost of guns, given the intuitive notion that second hand smoke and violence might be (conceptually) similar. I am not an expert on guns, and this is a quick post, given as food for thought.

I have done work on the social cost of cigarette smoking, and we estimated the cost per pack in to be ~$40 (in year 2000 dollars):

- $33/pack was private costs, mostly borne by the smoker through shortened life

- $5.50/pack was quasi-external costs, borne mostly by the spouse through shortened life via second hand smoke (and smaller amounts for children, who are exposed for shorter periods)

- $1.50 of external costs net of excise taxes which is the summation (positive and negative) of many sources: third party health insurance, Social Security, private life insurance markets, etc.

My colleague at Duke Phil Cook (along with Jens Ludwig at Chicago)Â have done work on the cost of gun ownership, and estimated what they call the social cost of a an additional household acquiring 1 gun to range from

- $100-$1,800/year per gun

More on the cost of smoking

A new paper in Health Affairs estimates the impact of smoking cessation on future health care costs among persons covered by TRICARE, taking account of changes in life expectancy.