Ethan Couch, a Houston 16-year-old, was given probation after having killed four people and grievously injured another in a drunken driving crash. (NYT account here.) At trial, a psychologist offered what’s subsequently been called the “affluenza defense,†suggesting that Couch should not be held fully accountable, since his upbringing in an extremely affluent family had made it difficult for him to develop the normal sense of responsibility for his actions.  The judge in the case rejected the prosecution’s call for a 20-year sentence in favor of probation and a stint at an expensive California rehab facility. Although teenagers responsible for vehicular deaths often escape prison terms, the decision provoked widespread outrage about how the legal system unjustly favors the wealthy.

The outrage provoked by the judges’s decision was totally justified, but the psychologist’s testimony about the effects of growing up in affluent circumstances was also essentially correct. That last fact should not have played any significant role in the sentencing process, but it’s highly relevant for broader questions of social and economic policy.

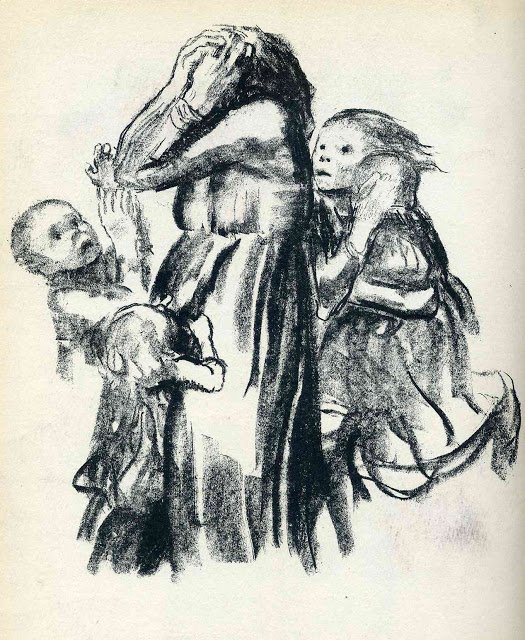

An emerging body of psychological research shows that people in relatively advantaged positions do indeed feel entitled to behave in many ways that would be considered off limits for ordinary people.  If you have a few minutes, watch this clip of Paul Solman’s interviews with some of the psychologists who’ve done this troubling work. There’s a reasonably solid foundation, then, for believing that someone who grew up in Ethan Couch’s circumstances would tend to have a diminished sense of responsibility for his actions.

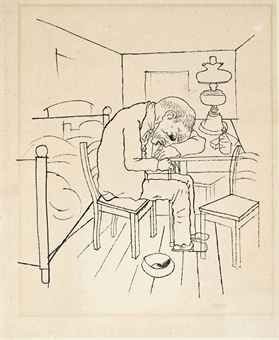

But it would be a mistake, I believe, for the justice system to treat him differently for that reason. The longstanding debate on free-will offers hints about how we might think about this issue. Â Children at birth differ enormously in ways that affect their adult behavior, often dramatically. Those who exhibit diminished capacity for self-control as small children, for example, are substantially more likely than others to commit crimes as adults. So in some meaningful sense, people born with such deficiencies are less responsible for their crimes. Â The same reasoning would logically apply to psychological tendencies shaped by environmental factors. Â People who were poorly brought up and misbehave as adults really are less culpable than people who were raised well yet misbehave in similar ways.

But except in extreme cases, society has wisely decided that our justice system should largely ignore such differences. Â The logic is that without a reasonable prospect of being punished for crimes, many more people would commit them. Even though some people are clearly more tempted than others by criminal opportunities, diminished moral inhibition is accepted as a mitigating factor only in the case of extremely mentally ill or handicapped individuals.

It’s an imperfect solution, to be sure.  But the alternative would be social chaos.  Ethan Couch’s upbringing may well have made him less able to embrace the idea that bad conduct could produce bad consequences.  But few of us would want to live in a society in which that fact exempted him from responsibility for harming others, because a society like that would have so much more crime and disorder. Warren Buffett and countless other rich people have demonstrated that it is possible to raise morally responsible children even in families with almost limitless wealth.  Society has no interest in sending a message that wealthy parents no longer need take that obligation seriously.

But rejecting the notion that affluenza exempts people from their responsibility to obey the law does not require us to reject evidence that extreme income inequality often promotes socially harmful behavior. That’s not a reason for lenient sentences, but it’s yet another reason to favor policies that would slow the current rapid growth in income inequality.