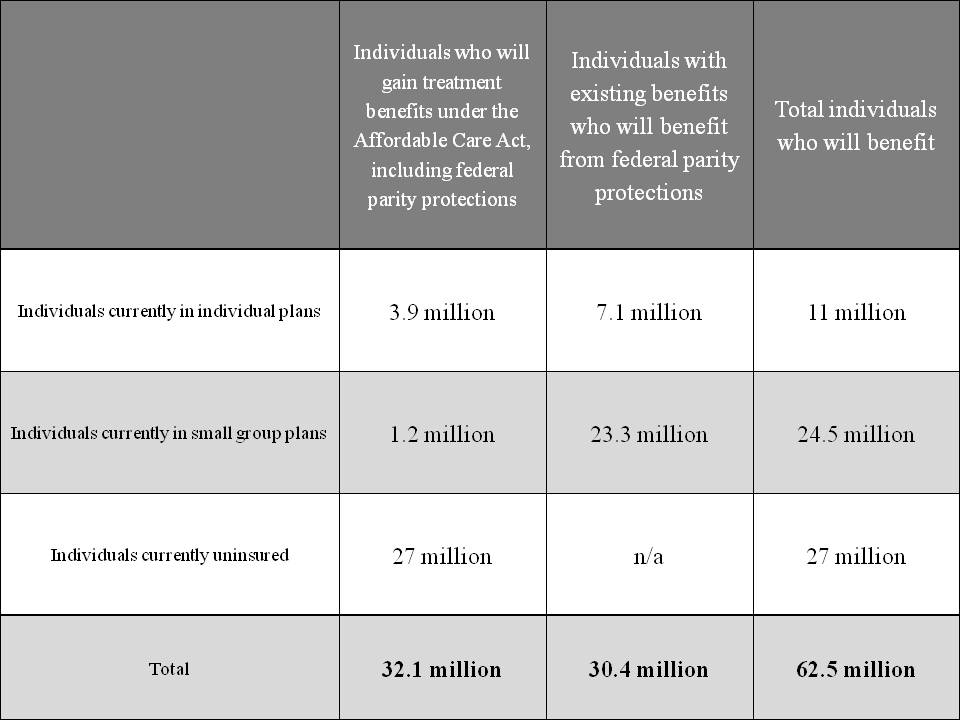

Given how often some people demand “health-oriented drug policy” from the Obama Administration it is more than a little peculiar how one of the biggest reforms in history didn’t attract more attention and draw more praise in the blogosphere. With the Administration’s declaration that treatment of mental health and substance use disorders are essential health care benefits, to be provided not only in the state health insurance exchanges but in all new individual and small-market health insurance plans, over 60 million Americans just got better insurance coverage for these disorders. The graphic below is from HHS:

That isn’t the end of the good news. The more than 100 million Americans who receive coverage under large-group plans are also getting better coverage due to the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act. Passed in the waning days of the G.W. Bush Administration with the regulations being written by the Obama Administration, the law mandates that any offered benefits for addiction and mental health must be comparable to those offered for other conditions.

But wait there’s more: Medicare, which enrolls almost 50 million people, has long had inferior coverage for addiction and mental health outpatient care, reimbursing only 50% of costs versus 80% of those for other forms of medical care. Thanks to a provision in the 2008 Medicare Improvements for Patients and Providers Act (again, give it up for the 110th Congress and President Bush), this disparity in reimbursement is being phased out and will be entirely eliminated by January 1 of next year.

When you consider that addictions almost always evidence themselves in adolescence or early adulthood, it becomes clear that the ACA provision allowing parents to keep children on their insurance until age 26 adds yet another layer of protection for the population.

Some people of course have coverage from more than one of the above sources, but even granting that overlap, over 200 million Americans have gotten improved insurance coverage for treatment of drug and alcohol problems (and mental health disorders as well). This includes many people who were starting with nothing, as well as a large population that had a benefit of inferior quality.

This is the biggest expansion to access to care for addiction in at least 40 years and probably in American history. In financial terms, it is certainly the biggest commitment of public and private resources to the health care of people with substance use disorders in U.S. History. Congratulations are in order to countless grassroots advocates, civil servants, political appointees, members of Congress and two U.S. President for transforming the face of health care for addiction.