I’m a fan of George Orwell. I think one of the most important pieces of writing in the English language, for example, is his set of rules for how to make the perfect cup of tea. In fact, I sometimes wonder whether people can really make a cup of tea, and therefore participate in civilised society, without following those rules; I often ungraciously request that my friends read Orwell’s piece before I permit them to hand me a brew.

Because of this general affinity for Orwell’s work, it’s always with some sadness that I look over his prescriptions for what constitutes good writing. He distils these into six rules:

- Never use a metaphor, simile, or other figure of speech which you are used to seeing in print.

- Never use a long word where a short one will do.

- If it is possible to cut a word out, always cut it out.

- Never use the passive where you can use the active.

- Never use a foreign phrase, a scientific word, or a jargon word if you can think of an everyday English equivalent.

- Break any of these rules sooner than say anything outright barbarous.

They cause me sadness because I know full well that I violate rules one through five fairly regularly – a violation that I justify by appealing to rule six. I recognise that my own style of writing – my modus scribendi – is all-too-often characterised by florid and pleonastic writing. ↠There you have it: twenty-one words in a sentence that would make Orwell spill his impeccably brewed tea all over his morning copy of Pravda. Cliché? Check. Aureate prose? Unquestionably. Prolixity? Naturally. Passive voice? Colour me checked. Argot? Affirmative. And yet, aside from being inelegantly constructed, I don’t see much of a problem with it. It conveys the point clearly, albeit pretentiously.

Ed Smith’s last column from the New Statesman argued that Orwell’s rules have been co-opted and deployed for precisely the nefarious purposes Orwell had hoped to prevent:

Orwell argues that “the great enemy of clear language is insincerity. When there is a gap between one’s real and one’s declared aims, one turns as it were instinctively to long words.â€

I suspect the opposite is now true. When politicians or corporate front men have to bridge a gap between what they are saying and what they know to be true, their preferred technique is to convey authenticity by speaking with misleading simplicity. The ubiquitous injunction “Let’s be clearâ€, followed by a list of five bogus bullet-points, is a much more common refuge than the Latinate diction and Byzantine sentence structure that Orwell deplored.

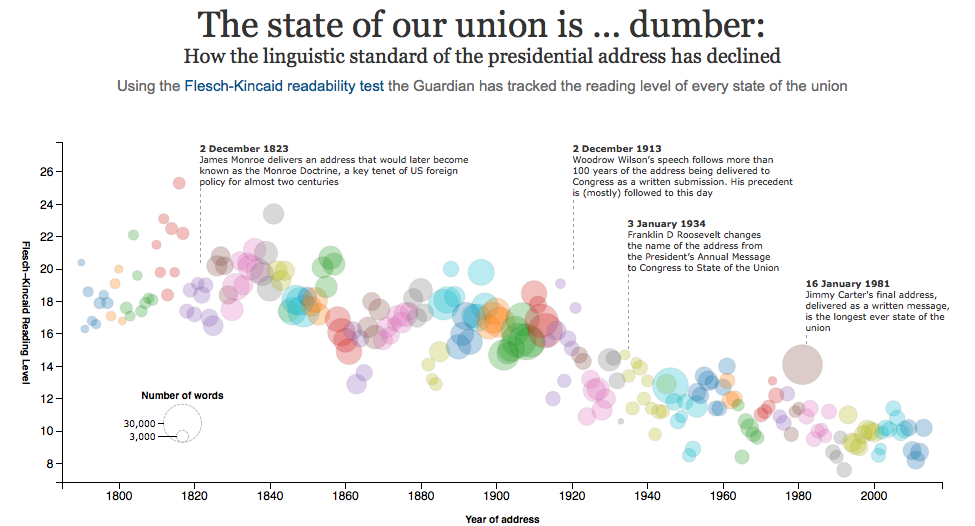

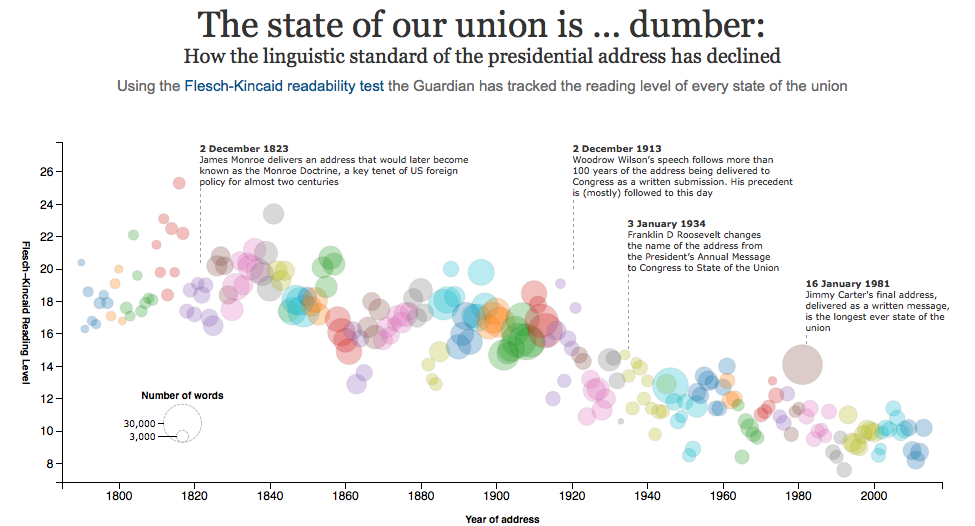

The argument seems plausible to me. Indeed, the Guardian has a lovely infographic that illustrates how SOTU speeches have adopted increasingly simpler vocabulary and syntax over time. You can decide for yourself whether this has accompanied more political duplicity, as Smith argues.

I enjoyed Smith’s post not just because I think the argument seems accurate. It’s because I’d like to think that in my own case, grandiloquent writing isn’t really the problem. Orwell’s concern was not with the choice of words (a stylistic concern); it was with the way words can be used to manipulate thoughts (a substantive concern). Hence, the dispositive sixth rule.

My take-away from Orwell’s writing rules, then, is that the sixth is the only true ‘rule,’ as it is the only one with substantive content – not to write anything barbarous. The preceding five ‘rules’ aren’t really rules at all. They’re more like suggestions, and Orwell didn’t have much of a bee in his bonnet for those.

Oops – a cliché. Damn that pesky first rule…