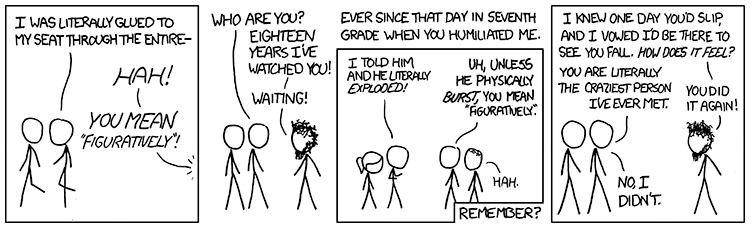

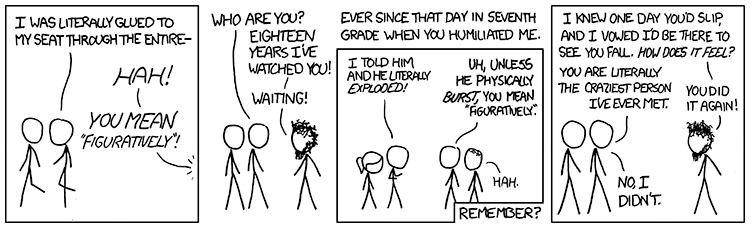

As noted by the Senior Editor of the Oxford English Dictionary, there’s been some consternation recently about the inclusion of a figurative interpretation of ‘literally’ to the list of acceptable definitions of the word.

What may surprise [people] is to find that th[e figurative] usage is much older than you would think. While it is true that it has become increasingly common in modern usage, it was actually first included in the OED in 1903. When the entry was updated and published online in September 2011, we found even earlier examples of this usage – our earliest example is currently from 1769…

I’m no lexicographer, nor am I a philologist by any stretch of the imagination. My knowledge of the terms ‘prescriptivist’ and ‘descriptivist’ just about exhausts my familiarity with the field.

Simon Winchester’s history of the OED did, however, make me think that inclusion of the figurative interpretation of ‘literally’ may in fact have been well overdue. If you haven’t read it, I encourage you to squeeze it in as (perhaps your final) summer read.* I won’t regurgitate the history, as much of the material can be found in condensed form at Wikipedia, or in far more entertaining and engaging form from the book itself. I’ll draw attention to just one aspect of the story: the Dictionary project emerged after a series of lectures that were delivered to the newly formed Philological Society convinced its members of the inadequacy of previous efforts (notable examples including Dr. Johnson’s). If the task was to succeed, the lectures argued, the English Dictionary would need to jettison the approach of having a committee decide on the correct usage of words by central diktat. While such an approach might have worked for languages like French or Italian, for which the rules and vocabulary were more rigid, the “mongrel†nature of English required a different approach altogether. Instead, an English Dictionary necessitated soliciting English speakers for suggestions of how words have been used, rather than how they ought to be used.

The Philological Society lectures argued that because English is such a mish-mash of different rules and practices, any lexicographer assembling an English dictionary would be forced to apply only the very lightest touch in providing guidance. Indeed, this is reflected in Ms. McPherson’s post. Back to her:

Whatever the reasons, it is clear that people often have strong opinions about “new†senses of words. Perhaps the question is not so much why do people have a problem with literally but rather why do lexicographers not have a problem? It comes down to that oft-spoke mantra – language changes. Our job is to document that for better or for worse. Except for us, there is no worse. We have to look at language objectively and dispassionately. Of course, part of our job is to give guidance on what might be acceptable when. That is why we label some words as slang and why we give a usage note at the offending sense of literally, making clear that although it is very common, it is considered irregular in standard English.

We’ve known for a long time what is meant when someone says “I literally can’t take any more.” It’s perfectly regular and comprehensible, and objection to its use is really just the same kind of snobbery as quibbling over whether ‘data’ is singular or plural. The answer: yes, technically, ‘data’ is a plural word, but if you want to treat it as such, you’re probably being a hypocrite in the way you use many other words. So you’re best off just sticking with what comes naturally (i.e., the singular). Moreover, as McPherson notes, the greatest harm (if any) is that a figurative use of ‘literally’ is pleonastic. All of this is just another way of saying that language use in English generally resorts to conventions rather than rules set out by lexicographers. The originators of the OED at the Philological Society have been vindicated, it seems.

In addition to being one of the most impressive and inspiring projects of which I know, the OED also strikes me as a model for one of the first ‘open-source’ data collection projects. With its practise of soliciting input on word usage from word users throughout the world, I wonder how much precedent can be found in the history of the OED in the formation of Wikipedia.

*By which I mean Winchester’s book. Then again, if you want to read the OED, …I suppose some people do that for fun.

TL;DR: