Is democracy so feeble that it can be undermined by a look or a line?

-Humphrey Bogart, protesting the investigation by the House UnAmerican Activities Committee (HUAC) into communist sympathies in Hollywood

Everyone is entitled to his own opinion, but not his own facts. Founded by Mark Kleiman (1951-2019)

One of Bogart’s best lines was delivered outside of a movie

Is democracy so feeble that it can be undermined by a look or a line?

-Humphrey Bogart, protesting the investigation by the House UnAmerican Activities Committee (HUAC) into communist sympathies in Hollywood

Alastair Sim and Michael Hordern collaborated on both live action and animated versions of A Christmas Carol, both remarkable films

RBC Weekend Film Recommendation is on holiday break this week, but here are two previously recommended movies well worth revisiting at this time of year:

RBC Weekend Film Recommendation is on holiday break this week, but here are two previously recommended movies well worth revisiting at this time of year:

Scrooge: Alastair Sim and Michael Hordern lead a perfect cast in the best live-action adaptation of Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol.

A Christmas Carol — The best animated adaptation of the same story is eerie and utterly original. Wonderfully, it features Sim and Hordern among the voice actors.

Cary Grant and Loretta Young’s film The Bishop’s Wife makes for wonderful Christmas viewing

The only people who grow old were born old to begin with.

The only people who grow old were born old to begin with.

If you were asked to recall a 1947 Christmas movie that was nominated for a best picture Oscar, you would probably come up with the famous Miracle on 34th Street. But remarkably, it was only one of two Christmas films so honored that year. The other is this week’s film recommendation: The Bishop’s Wife.

Anglican Bishop Henry Brougham (A miscast but appealing David Niven) is under strain as he attempts to raise money for a new cathedral. Donations are not arriving, and the wealthiest woman in town (Gladys Cooper) will only help if the building is made into a tasteless monument to her late husband. Meanwhile, since becoming an Archbishop consumed with finances and grandiose plans, Henry has been drifting apart from his long-suffering wife Julia (the ever-luminous Loretta Young). He prays to God for aid and a friendly, dashing, sharply dressed fellow arrives at his office (Who else but Cary Grant?). Calling himself Dudley, the new arrival says he is here to help, which Henry takes to mean help raising money. But Dudley spends most of his time trying to restore Julia’s happiness instead, much to Henry’s irritation.

Some films live or die on the strength of a star’s charm, and this is an example of a film living, indeed thriving, on the charm of the inimitable Grant. Director Henry Koster seems to have instructed every female member of the cast to swoon upon meeting him, and it’s utterly believable given with warmth and gentleness that the handsome Grant radiates in ever scene. Loretta Young’s devout-and-goodly performance is perfectly matched to Grant’s, as the story requires their relationship to be intimate but at the same time innocent. She was at the peak of her powers in 1947, during which she not only garnered raves for her role in the Bishop’s Wife but also won a Best Actress Oscar for The Farmer’s Daughter.

Grant and Young get strong support from the rest of cast, particularly Monty Woolley as an atheistic retired college professor who is an old friend of Julia and Henry’s. The Robert Mitchell Boy Choir are also on hand for a mellifluous number in Henry’s former and very poor church, a symbol of the simpler faith and life that he has lost.

The Bishop’s Wife rewards the eye as well as the heart, thanks to Gregg Toland being behind the camera. The town looks lovely, peaceful and Christmassy as can be. And Toland gets to be Toland, as you see on the left, which is my favorite shot in the movie, during which the characters slowly accrue at different depths away from Grant, who is making an emotional and religious connection to Henry and Julia’s little girl (played by Karolyn Grimes, who essayed a similar role in It’s a Wonderful Life).

The Bishop’s Wife rewards the eye as well as the heart, thanks to Gregg Toland being behind the camera. The town looks lovely, peaceful and Christmassy as can be. And Toland gets to be Toland, as you see on the left, which is my favorite shot in the movie, during which the characters slowly accrue at different depths away from Grant, who is making an emotional and religious connection to Henry and Julia’s little girl (played by Karolyn Grimes, who essayed a similar role in It’s a Wonderful Life).

The Bishop’s Wife is not a film for the cynical nor for those hostile to religious messages. But if the Christmas spirit animates your heart at this time of year, you will find much to love in this extraordinarily sweet movie.

I embed below the amusing “un-trailer” of the film, featuring the three leads and absolutely, positively no spoilers.

1973’s The Wicker Man has deservedly attained cult status as an original, exceptional horror film

Our Edward Woodward tribute continues this week with a big screen triumph he made not long after the Callan TV show ended (RBC Recommendation here). This week’s recommendation is an unconventional low-budget horror film that has no monsters or ghosts, includes almost no night time scenes, blood, gore or special effects, yet is unquestionably harrowing: 1973’s The Wicker Man.

The plot: Uptight, devout and dedicated Police Sergeant Howie (Edward Woodward) arrives alone by seaplane at a small Scottish island to investigate reports that a little girl has gone missing. He finds a strange community of back-to-nature types who claim never to have heard of the girl, much to Howie’s frustration. He is further inflamed by their paganistic world view, sexual expressiveness and apparent disregard for his authority as a representative of HMG. He eventually meets the head of the community, Lord Summerisle (Christopher Lee), who confounds him further even while ostensibly supporting his quest to find the missing girl. His anger and anxiety mounting, Howie presses his investigation to the limit, but matters become only more maddening and much, much more dangerous.

It’s easy to see why Christopher Lee, who has made almost 300 films, declared that this was the best one he was ever in. He, Woodward, and the actors in other key roles (Diane Cilento and Britt Ekland) give performances that are somehow both realistic and otherworldly at the same time. And Anthony Shaffer’s script has the perfect set-up for suspense: A man absolutely alone in a strange place that he cannot understand and in which no help is available.

In addition to being scary, The Wicker Man is also sensually pleasurable. It features among other sexually charged moments one of the most erotic and original seduction scenes in the history of film. The soundtrack is also rich and stimulating. It would have been easy to simply have the music of the islanders be a recycled collection of old Celtic folk songs, but instead Paul Giovanni composed authentic sounding music that adds immeasurably to the atmosphere.

Warning: This film had an unhappy history post-production, with many cuts being made both by studio suits who didn’t get the film and morality police who hated the sex. The lack of respect for the film at the time is best expressed by the fact that the negative ended up buried beneath the M4 motorway (not a joke, sadly). Work very hard to get as long a cut as you can; Wikipedia has an account of all the versions here.

I hope you will take the time to discover this cult classic of British horror cinema. After the jump, I offer an interpretational addendum for those of you who have already seen it.

Continue reading “Weekend Film Recommendation: The Wicker Man”

Brian De Palma’s “The Untouchables” is fantastic update of old time gangster movies with knockout performances by Robert De Niro and Sean Connery

Many classic TV shows have been made into dreadful movies, but Brian De Palma came up aces in 1987 when he made this week’s film recommendation: The Untouchables.

Many classic TV shows have been made into dreadful movies, but Brian De Palma came up aces in 1987 when he made this week’s film recommendation: The Untouchables.

The plot: Naive treasury agent Elliot Ness (Kevin Costner) comes to Prohibition-era Chicago to do battle with bootlegger, murderer and king of the gangsters Al Capone (Robert De Niro). Realizing that the police and politicians are all corrupted by Capone, Ness assembles his own team of “untouchable” agents who can’t be bought. His squad is anchored by a cynical, over-the-hill beat cop named Jim Malone (Sean Connery), who teaches him how the game is played in the Windy City. The two of them and their fellow untouchables embark on an epic confrontation with powerful, violent mobsters and a legal system that is rotten from top to bottom.

The key theme of the film is voiced by Connery, in one of the many scenes where he virtually acts the bland Costner right off the screen: What are you prepared to do? The basic tension of David Mamet’s crackerjack script derives from the fact that the good guys can’t win without breaking the rules they have sworn to uphold. This adds moral weight to a story that is also packed with thrilling action sequences and powerful dramatic moments.

De Palma often echoes classic films in his movies, and The Untouchables is no exception. A spectacularly executed shoot-out sequence in Union Station is an homage to the equally brilliant Odessa Steps sequence in Battleship Potemkin. Although I don’t know for sure, I believe the first scene of the movie, in which a terrified barber reacts to having nicked Capone’s face while shaving him, is an echo of one of the opening scenes of a prior RBC recommendation: The Chase. De Palma makes these allusions is such a way that you don’t have to get them to enjoy the film, but if you do it’s even more fun.

This was a big budget Hollywood film and it shows in every scene. The set design and art direction are darbs, and the period cars, clothes and architecture are the cat’s meow. Producer Art Linson is a Chicago native, and clearly knew where to spend money to bring the Prohibition Era alive. To top it all off, Ennio Morricone contributes one of the most memorable and evocative scores of the 1980s.

Other than Costner, who is painfully weak here, the entire cast explodes. But even in that field, Connery and De Niro tower over everyone with powerhouse performances. Capone has been portrayed many times on film, but never in such a scary fashion. In De Niro’s hands, he is a man who can go from mirth and charm to murderous rage with no warning, and the viewer fully appreciates why all of his underlings tiptoe around him.

Other than Costner, who is painfully weak here, the entire cast explodes. But even in that field, Connery and De Niro tower over everyone with powerhouse performances. Capone has been portrayed many times on film, but never in such a scary fashion. In De Niro’s hands, he is a man who can go from mirth and charm to murderous rage with no warning, and the viewer fully appreciates why all of his underlings tiptoe around him.

Connery, who won a long-overdue Oscar for playing Malone, also tears up the screen. His Malone is world-weary and tough yet also capable of wit and even a sort of gentleness (His big brother-little brother relationship to Andy Garcia’s rookie cop is perfectly played by the two actors). Because he became famous playing James Bond, it took Connery a long time to convince people that he really is a fine actor. I have commended his strong performances in RBC recommendations many times, including in The Hill and Outland. He triumphs again in The Untouchables, one of many reasons to see this near-perfect update of classic cops-versus-gangsters television shows and movies.

The Howling is a werewolf tale with astonishing special effects and a smart-alecky John Sayles script filled with in-jokes for fans of the genre

Let’s wrap up three weeks of pre-Halloween scary movies with a film that’s more packed with references to other horror films than Scream: Joe Dante’s 1981 cult favorite, The Howling.

Let’s wrap up three weeks of pre-Halloween scary movies with a film that’s more packed with references to other horror films than Scream: Joe Dante’s 1981 cult favorite, The Howling.

Originally intended as a straight-ahead werewolf film, it was changed significantly in tone by a late-arriving co-screenwriter, the ever-creative John Sayles. Sayles kept the scary bits, but added a pile of in jokes and satiric moments (including one with himself as a coroner). The result was unsatisfying to some viewers, but the movie returned its modest budget many times over as horror fans embraced it enthusiastically.

The story opens with earnest, All-American TV reporter Karen White (Dee Wallace) putting herself in danger to help capture a serial killer who has developed an obsession with her. Despite police backup (actually, BECAUSE of police backup), things go horribly awry and she is psychologically traumatized. With the support of her ex-Stanford football star husband Bill Neill (Christopher Stone) she seeks treatment from a pompous psychiatrist who emphasizes the need to release the beast within (Patrick Macnee). He sends Karen and Bill to “the colony” an Esalen-type retreat, for healing. What the innocent couple don’t know is that the colony is a den of werewolves, and before you can say “Aaahooooooooo” they are both being terrorized by a motley assortment of lycanthropes!

The budget apparently prevented the casting of any A-listers, but the performers do a serviceable job, especially MacNee, who gamely spouts 1970s psychobabble, and the sultry Elisabeth Brooks, who memorably redefines the term “maneater”. But the real stars are Sayles’ parade of little gags (everyone eats Wolf Chili and drinks Wolf’s Liquor; look fast also for a copy of Ginsberg’s Howl), and the astonishing person-to-wolf transformations of Rob Bottin. Bottin leaves the CGI-dependent special effects artists of today in the dust with his extraordinarily scary work here.

The film has some flaws. After a gripping opening 20 minutes, it shifts the pace to neutral for too long before revving up a thrilling final act (In fairness, the film is over 30 years old, so perhaps a little flab in the middle is forgivable). I can understand also that the smart-alecky script may elude some viewers or seem to precious to others. But for horror movie buffs, The Howling is a fun screamfest that will enliven your Halloween.

And, now A TRIVIA QUIZ, with answers after the jump, with all the questions deriving from Sayles’ script flourishes.

1. MacNee’s character is named George Waggner. The real Waggner directed what horror classic?

2. One member of the colony is named Erle Kenton, after the director of the spooky 1945 movie House of the Dracula. The actor playing Kenton in The Howling was actually IN that movie. Who is he?

3. Early in the film, when Karen White is in a phone booth waiting to meet serial killer Eddie Quist, a tall man stands just outside the door. Is he waiting to use the phone, or is he the killer, blocking her escape? Well, when he turns to face the camera he is revealed to be a famous horror movie director. Who? Hint: I recommended one of his films very recently.

4. Stone’s character is named after R. William Neill, who directed what great horror “team-up” movie?

5. Noble Willingham plays a character named Charlie Barton. Barton directed what famous comedy-horror mashup?

Continue reading “Weekend Film Recommendation: The Howling (Plus a Trivia Quiz!)”

I just watched Mark Stevens’ excellent 1956 film noir Timetable. There was a funny movie trope during the robbery scene portrayed above. After the robber blows the safe, he steals “$500,000 in small bills”. The money is contained in two small satchels each about the size of a woman’s purse, which he almost daintily lifts and then tosses into his suitcase.

In real life, a piece of US currency is .0043 inches think and weighs about a gram. If we assume the average “small bill” is a $10 note and that the bills are all perfectly pressed flat with no wrinkles, the stack of bills should have been 17.92 FEET high and would have weighed just over 110 pounds!

But in the movies, money is small and light. Countless caper films feature people nimbly running around with zillions of dollars in their small, lightweight satchels.

Does anyone know any movies that undo this trope, for example by having a kidnapper not be strong enough to lift the suitcase with the ransom in it, or having a car axle bend under the weight of the multi-billion dollar haul in the back seat?

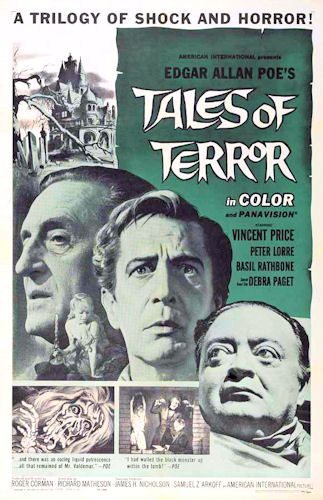

Roger Corman’s spooky, campy film “Tales of Terror” is ideal for Halloween viewing

As Halloween approaches, it seems a good time to recommend one of the many Edgar Allen Poe films of low budget whiz Roger Corman: Tales of Terror.

As Halloween approaches, it seems a good time to recommend one of the many Edgar Allen Poe films of low budget whiz Roger Corman: Tales of Terror.

This 1962 film is a trilogy of stories based on four different Poe stories: Morella, a pastiche of The Black Cat and The Cask of Amontillado, and The Facts in the Case of M. Valdemar. The stories are well-employed in the script of the late, great Richard Matheson, whose ability to infuse new, um, blood, into hoary tales I have praised here at RBC before. Vincent Price anchors the film with three lead performances, which vary in tone from lugubrious to frothy to sepulchral.

Price is joined by two aging stars who still know how to deliver the goods. Peter Lorre makes a fine boozy bully in The Black Cat and Basil Rathbone lends gravitas to the role of Carmichael, the hypnotist who tries to hold Valdemar at the point of death in the final story. The roles of the women characters however are comparatively flat, with the female performers cast mainly for their looks.

Many horror films, including some of the most famous, include some element of camp, and Tales of Terror is very much in that tradition. Price and Lorre enjoy themselves enormously in The Black Cat, inviting the audience to laugh at them as much as be frightened by the murderous proceedings. As a viewer, you should bring eggs for this part of the film, because these guys are bringing the ham.

Many horror films, including some of the most famous, include some element of camp, and Tales of Terror is very much in that tradition. Price and Lorre enjoy themselves enormously in The Black Cat, inviting the audience to laugh at them as much as be frightened by the murderous proceedings. As a viewer, you should bring eggs for this part of the film, because these guys are bringing the ham.

In addition to the tension and fear generated by the three stories, the film makes for good horror viewing because Corman, as always, was experimenting as he went along. Some novel special effects are on display, all of which work pretty well. On the small screen, some of the Cinemascope trickery at the screen edges will be lost, so see this one on the big screen or in letterbox format if you can.

In some people’s minds, Corman is nothing but a schlock merchant, but that’s not fair to him. Like Richard Rodriguez, he has a genius for improvising in a low-budget environment. He shot movies on the sets of other movies while they were being torn down, writing a script each night to take advantage of whichever set would be gone by the end of the next day. He told Peter Bogdanovich that “Boris Karloff owes me a few days of filming, let’s make something out of that”, which became the nail-biting Targets. And he also helped launch many future superstars, including Jack Nicholson, Peter Fonda, Charles Bronson, Jonathan Demme, Martin Scorsese, Ron Howard, and Francis Ford Coppola. I was absolutely delighted when Hollywood finally woke up and gave the 83-year old Corman an Academy Award for Lifetime Achievement, because he’s long been the kind of disruptive, creative force that the film industry needs to maintain its vitality.

p.s. Interested in a different sort of film? Check out this list of prior RBC recommendations.

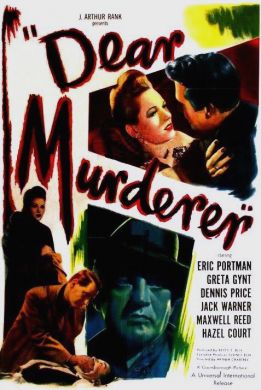

Dear Murderer is an urbane, nasty and entertaining late 1940s Britfilm noir

Have you been sleeping with my wife, my dear chap?

Have you been sleeping with my wife, my dear chap?

Yes old man I’m afraid I have been. Cigarette?

Thanks awfully. You realize old bean that I’ll have to murder you of course.

I’d think very little of you if you didn’t. Care for some Scotch?

I have a weakness for Brit movie dialogue that is completely savage in message while being unctuous in delivery. Such lines are the most delicious aspect of Ray Milland’s murderous character in Dial M for Murder (reviewed at RBC here), and they are also a virtue of this week’s equally suave-and-nasty film recommendation: 1947’s Dear Murderer.

Made by the Box family during the brief life of Gainsborough Studios in South London, the film stars the smooth Eric Portman as a man who discovers that his flash, icy wife has been stepping out on him while he has been in America. In the movie’s best scene, he visits the man whom he has discovered is her lover (Dennis Price), and after some perfectly mannered exchange of pleasantries, announces that he is going to murder him. Things do not go quite to plan however, not least because wifey hasn’t been limiting herself to one beau. It only gets colder and nastier from there, with plot twists aplenty and entertainment value to spare.

Portman and Price’s urbane, scary face-off is brilliantly done, and it is a shame that it wasn’t the first scene, which would have started the film off with a bang (The first scene instead is some unneeded background exposition to explain how the infidelity was discovered..I so dislike it when filmmakers don’t just tell the story from the get go). An irony of the scene for modern audiences is that the actors playing the two men battling over their shared love of a woman were both gay. It would have been interesting to be a fly on the wall afterwards to hear the actors discuss between themselves how they played the scene and how they felt about it.

As for the woman herself, Greta Gynt is a revelation as the twisted, narcissistic wayward wife. Like Lizabeth Scott in No Time for Tears (passionately praised here at RBC) Gynt plays a far more scary character than the murderous men around her. The delight on her face when she realizes that desire for her has led one man to murder another is chilling. Few Americans have heard of Gynt because despite significant success in British films in the 1930s and 1940s, she never caught hold in Hollywood. After you have seen this film, you will want to put in the effort to find more of her movies.

Even as film noirs go, this one is pretty dark. There are only two morally decent characters, neither of whom is very interesting. You may find yourself rooting for some bad people at least some of the time, even if by the end you are glad they get what they had coming to them.

p.s. Interested in a different sort of film? Check out this list of prior RBC recommendations.

No doubt you have often said “I’d love to watch a 1947 Douglas Sirk movie starring Lucille Ball and Boris Karloff that was a remake of a French film and was re-made again a half century later with Lucy’s part played by Al Pacino.” Okay, you’ve never said that, but nonetheless it’s this week’s film recommendation: Lured.

No doubt you have often said “I’d love to watch a 1947 Douglas Sirk movie starring Lucille Ball and Boris Karloff that was a remake of a French film and was re-made again a half century later with Lucy’s part played by Al Pacino.” Okay, you’ve never said that, but nonetheless it’s this week’s film recommendation: Lured.

The film tells the exciting story of the hunt for a serial killer who finds his young female victims though the newspaper’s “personal column” (This eventually became the title of the movie in the US after the Production Code censors ruled that “Lured” sounded too much like “Lurid”!). The fiendish villain taunts the police by sending them poems about his next intended victim. When another young woman is murdered, her plucky pal and fellow dance hall gal (Lucille Ball) feels it’s her duty to help a police inspector (Charles Coburn) catch the killer. Shadowed discreetly by a police minder (George Zucco), she starts answering ads in the personal column, which leads to dates which are by turns funny, disappointing and disturbing. Meanwhile she finds herself falling for a smooth-as-silk impresario (George Sanders) who with his business partner (Cedric Hardwicke) runs a chic club in which she hopes to audition as a dancer after the mystery is solved. But as she tries to decide whether to trust her beau enough to tell him of her work with the police, evidence emerges that he may somehow be connected to the case!

Many people only know Ball as Lucy Ricardo, but in fact she turned in some good performances in dark, dramatic films prior to ruling American television comedy for a quarter century. Lured and The Dark Corner are the best of her film noir work.

Ball had the fortune to launch her film career in a period when it was acceptable for female performers to be both funny and physically attractive. For most of the last half of 20th century, these attributes were often perceived as incompatible by entertainment moguls: Actresses were usually pigeon-holed as comic or sexy, but not both. My favorite example of this phenomenon was that Phyllis Diller was once going to do a Playboy spread as a joke, but when they took the photos it turned out that she looked beautiful under that house dress. The project was therefore shelved. Tina Fey and Amy Poehler are among the stars of today who have helped break down this constraint, restoring the possibility for other women to essay more multi-dimensional roles like Ball did in the late 1940s.

Ball is only one of the performers in Lured from whom Sirk got the very best. George Sanders played the sophisticated British rake in many movies and he does it yet again here. But so what? He’s very fun to watch doing what he does best. Coburn as the police inspector is appealing, particularly in his father-daughter style interactions with Ball. George Zucco, normally cast as a villain, shows a fine comic touch. Karloff is only on screen for one extended sequence, but nearly steals the movie as a deranged, grief-stricken has-been obsessed with the past. Last but not least, Hardwicke does well in perhaps the most complex part as Sanders’ business partner. The subtext of his emotions regarding Sanders and Ball is brought out subtly, in a way that clearly eluded the censors at the time. That is also a testament to Douglas Sirk, who loved to tell overtly conventional stories with implicit, then unacceptable, undertones that only some of the audience appreciated.

Lured is also a fine-looking picture, as you would expect when the camera in the hands of William Daniels. Sirk clearly influenced at least some of the shot framings, as they strongly prefigure the scene compositions he would employ in his 1950s heyday.

Lured is also a fine-looking picture, as you would expect when the camera in the hands of William Daniels. Sirk clearly influenced at least some of the shot framings, as they strongly prefigure the scene compositions he would employ in his 1950s heyday.

Lured does have some problems with tone and pace. It’s effort to mix comic, suspenseful and disturbing elements simply doesn’t always work. There are also some draggy moments that should have been left on the cutting room floor. One has to ask as well why the movie is set in London when it clearly was not shot there and Coburn’s police inspector sounds thoroughly American. Collectively, these flaws keep Lured in the good rather than great category.

If the story of Lured appeals to you, you might enjoy the other two above-average efforts to adapt it to the screen: The 1939 French movie Pieges directed by Robert Siodmak, and the 1989 U.S. film Sea of Love with Al Pacino and Ellen Barkin.

p.s. Look fast for Gerald Hamer in an uncredited small role in the dance hall early in the film. He was an essential part of a prior RBC recommendation: The Scarlet Claw.

p.p.s. Interested in a different sort of film? Check out this list of prior RBC recommendations.