RBC Weekend Film Recommendation takes a break from recommending movies this week in favor of recommending the next best thing: A book about the movies! And with it I commence a month-long tribute to Dana Andrews. I have always found him intriguing because he was such a towering star in the 1940s, anchoring films of superlative quality that were also wildly popular with audiences, including A Walk in the Sun, Laura and of course The Best Years of Our Lives. But beginning in the 1950s his career dissipated very rapidly and few people today even remember his name. What happened to this talented and toothsome actor, who seemed poised to dominate the screen for decades as did similar performers such as Henry Fonda and Gregory Peck?

RBC Weekend Film Recommendation takes a break from recommending movies this week in favor of recommending the next best thing: A book about the movies! And with it I commence a month-long tribute to Dana Andrews. I have always found him intriguing because he was such a towering star in the 1940s, anchoring films of superlative quality that were also wildly popular with audiences, including A Walk in the Sun, Laura and of course The Best Years of Our Lives. But beginning in the 1950s his career dissipated very rapidly and few people today even remember his name. What happened to this talented and toothsome actor, who seemed poised to dominate the screen for decades as did similar performers such as Henry Fonda and Gregory Peck?

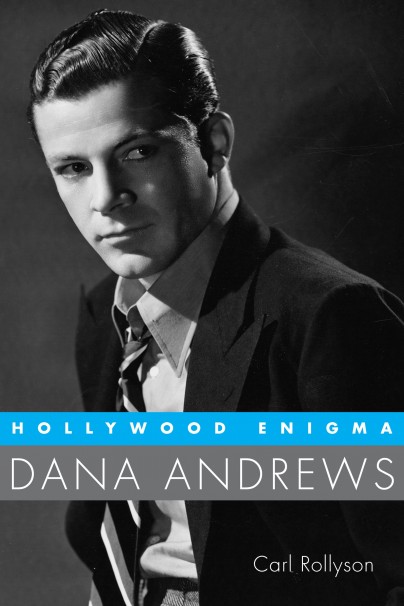

That’s one of the central questions addressed by Carl Rollyson’s fine recent biography Hollywood Enigma: Dana Andrews. Nothing else written about Andrews over the years pulls together so many sources of information so skillfully, making this likely the definitive biography of the man for all time. Crucially, Rollyson obtained the support of Andrews’ family and with it access to home movies, letters and anecdotes that get beneath the glossy images that the Hollywood publicity machine creates for its stars.

Rollyson makes clear that Andrews’ path to Hollywood was neither certain nor easy. Dana’s domineering, colorful father was a Baptist preacher in Texas and money was at times tight in the large Andrews clan. Dana and his siblings worked at odd jobs to keep the family afloat, and even as he was later getting a foothold in Southern California theater, he was still driving trucks to make ends meet during The Great Depression. His humble origins may have accounted for why, throughout his life, he remained an unpretentious regular guy more comfortable with the average person on the street than the glitzy Hollywood types who came to surround him when he became a star. It also helped account for him later becoming an avid New Dealer who loathed the political rise of Ronald Reagan (Both Reagan and Andrews would serve as President of the Screen Actors Guild).

Through extracts from love letters Rollyson movingly conveys the central conflict of Andrews’ young adult life. Dana had moved to California and was excited by what he might achieve there. But he was still strongly attached to his long-time girlfriend back in Texas. A painful choice had to be made and he ultimately broke off the engagement with the girl-next-door and married a woman he had met in his new life. Yet he stayed lifelong friends with his first girlfriend, whom he probably recognized understood him and loved him in a way that the many women who later swooned over the famous star never would.

After success in theater, Andrews began to land movie parts of growing significance. He was the epitome of a certain kind of masculinity that was cherished in that era. Outwardly strong, noble and fearless on screen, he simultaneously conveyed, in a minimalistic and naturalistic way, churning emotion underneath. Clearly, he had a handsome face, but it was what was going on underneath that transfixed most movie-goers. Rollyson dissects Andrews’ most critical roles well, helping the reader understand both Andrews’ talents and how some directors (but not others) knew how to maximize them.

In the mid-to-late 1940s, Andrews was one of the most beloved, most highly-paid movie actors in the world. But how many people remember him today compared to Bogart, Peck and Fonda, or even Fred MacMurray, who attained similar heights in that era? Andrews’ steep decline fascinates Rollyson and he goes a long way towards sorting out why it happened. Continue reading “Weekend Film Recommendation: A Tribute To Dana Andrews Begins”