The Democratic slogan on crime should be “Unburden the police,” specifically: fund community-based violence interruption programs; fund first-response mental health programs; eliminate traffic stops. With those things off their plates cops can focus on crime-solving/case clearance.

We shouldn’t minimize the reasons communities have for hating and fearing police practices, but we also can’t minimize the reasons those same communities have for wanting protection from crime. So reform the practices: spend less person-power on routine interference with citizens (whether pedestrian stop & frisk or traffic stop & harass) and more on solving crimes (which will be easier when people don’t suffer constant adversarial or humiliating or even fatal interactions with cops). And turn violence interruption over to community groups trained in its successful practice (like those that provided Chicago with a fairly peaceful Memorial Day weekend) and mental health crises over to professionals trained to handle those encounters.

And then use the right rhetoric! “Unburden the police” means exactly the same thing as “defund the police” but sounds pro- instead of anti-cop, anti- instead of pro-crime. “Fight crime smarter not harder.” “Build policing back better.”

Let’s stop leading with our chins on an issue where we have the right answers and our “Blue Lives Matter” opponents have nothing to offer.

Tag: Crime Control

Violent Crime and Imprisonment

Most people in state prison are there for a violent offense

Dana Goldstein at the Marshall Project has created a useful interactive graph showing who is in prison and how we might build further on the de-incarceration trend which started five years ago. Goldstein also echoes a point that Mark Kleiman and I have made here many times: It’s a myth that prisons are full of non-violent drug offenders.

The chart below presents Bureau of Justice Statistics data on state prisons, which is where almost 90% of U.S. prisoners reside. Violent crime has consistently been the leading cause of imprisonment, and most state prison inmates are serving time for a violent offense. Importantly, the data reflect current controlling offense only and thus understate the proportion of prisoners who engage in violence: Many inmates currently serving time for a non-violent offense have prior convictions for violent crimes.

These data make de-incarceration more complex in at least two ways , which is perhaps why so many people don’t want to believe them.

First, the noble ongoing efforts to reduce the size of the prison population should take substantial care to protect public safety as violent offenders are released. Mass dumping of violent offenders into communities with no monitoring and no services would be dangerous for them, for their families, and for their neighbors. Further, if it leads to released prisoners committing high-profile acts of violence, it could also choke off political support for continued de-incarceration.

Second, even assuming the best of all policy worlds in which reducing incarceration continues to be a priority, the U.S. is probably too violent of a society to ever shrink its prison population to a Western European level. The proportion of the U.S. population that is serving time for violent crimes is larger than the proportion of the Western European population that is serving time for all offenses combined.

Have “black sites” come to Sweet Home Chicago?

The Guardian and The Atlantic have now both reported that Chicago police maintain a site at which they interrogate suspects without booking them or letting them talk to their lawyers. On the Huffington Post, this is what I have to say about that.

As it turns out, this news doesn’t come too late to have an impact on the race for mayor in Chicago. Perhaps we can use the six weeks before the runoff election to ask Rahm what he knows about these sites, and when he knew it.

The Link Between Overcrowded Prisons and a Certain Drug

Over the past few months, I have given some talks about public policies that could reduce the extraordinary number of Americans who are in state or federal prison. The audiences in every case were blessedly bright and engaged. Yet they also had a broadly shared misunderstanding about how two drugs are related to the U.S. rate of imprisonment.

At each talk an audience member expressed the view that over-incarceration would drastically diminish soon because states were now legalizing marijuana. I responded by asking everyone present to shout out their estimate of what proportion of people currently in a state or federal prison were serving time for a marijuana-related offense. The modal answer across audiences was around one third, which explains the shocked looks that greeted my pointing out that even under the most liberal possible definition of a marijuana-linked incarceration (e.g., counting a marijuana trafficker with 10 other felony convictions as being in prison solely due to marijuana’s illegality), perhaps 1% of the U.S. prison population would be so classified.

Not wanting to discourage people, I said that there was a different drug that was responsible for many times as many imprisonments as marijuana and for which we could implement much better public policies. I then asked people to guess which drug it was. Give it a try yourself (answer after the jump). Continue reading “The Link Between Overcrowded Prisons and a Certain Drug”

David Kennedy on reducing violence

We know how to do it. It doesn’t depend on random stop-and-frisk.

If you care about homicide, click through. Key points: We know how to reduce bloodshed, and violence suppression doesn’t depend on indiscriminate, intrusive use of police power. Again: We know how to do it.

Note to Radley Balko: Congratulations on your new gig at the Washington Post. Your criticisms of police excess - often spot-on - would have more cred if, just once, you celebrated police success, or noticed that liberty can be threatened by crime as well as by official misconduct.

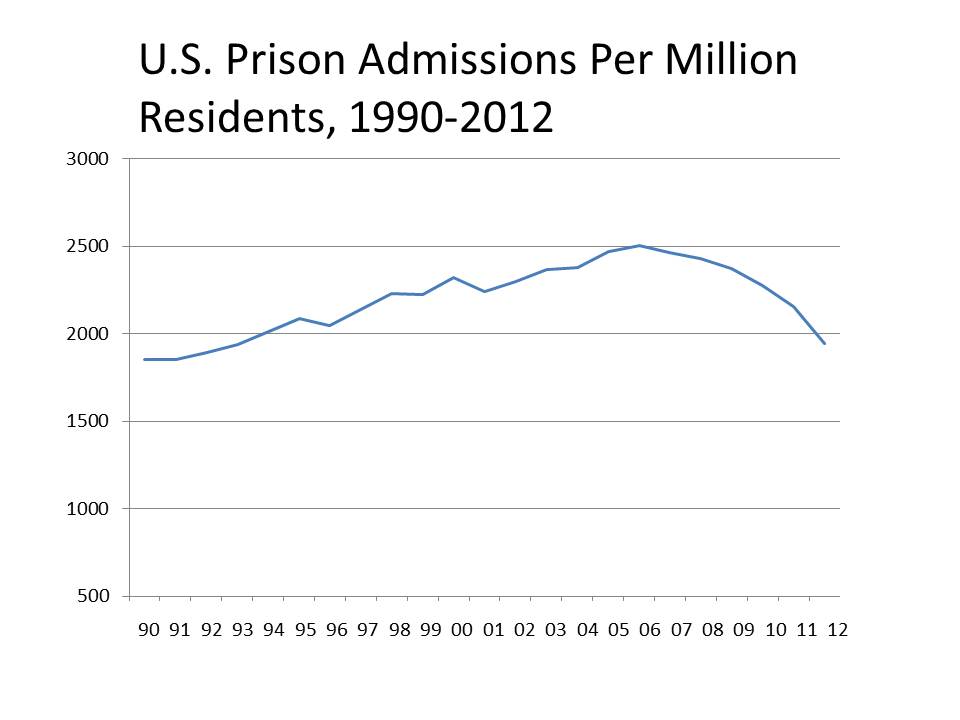

U.S. Prison Admissions are at a Two-Decade Low

Per capita admissions to prison are at a 20-year low

Like most people who write about trends in incarceration, I generally focus on how the size and nature of the entire U.S. prison population changes from year to year (e.g., here). This sort of analysis can reveal important things, for example that after rising every year for more than three decades, the size of the prison population has been dropping for three years in a row. But at the same time, such analyses tell us little about what state and federal policymakers are doing regarding prisons right now.

All policymakers are at some level trapped by decision accretion, and prisons are a perfect example of the phenomenon. The high level of incarceration in the U.S. is the product of decisions made over many years prior to when the current group of policymakers was on the scene. For example, while I have complained about the abolition of federal prison parole as a cause of overcrowding, I also recognize that many of the elected officials who voted for it have died of old age, and hardly any are still in office. Even if the current Congress re-established parole tomorrow, it would take years to unring that bell. Likewise, people who have committed heinous crimes for which they are serving multi-decade sentences do not simply evaporate with each election. And that’s critically important in evaluating how quickly current policymakers can reduce incarceration levels given that the majority of the state prison population is composed of violent offenders who are serving long sentences.

To try to get around this analytic problem of decision accretion swamping recent trends, I used the latest Bureau of Justice Statistics data to compute the annual rate of admissions to state/federal prison. As the chart below reveals, the large amount of recent change in this variable was obscured in my prior analyses, which looked only at total prison population size. I was startled and encouraged to see that under current policies, we are at a two decade-year low in the prison admission rate. To provide historical perspective, peg the change to Presidential terms: When President Obama was elected, the rate of prison admission was just 3% below its 2006 level, which was very probably the highest it has ever been in U.S. history. But by the end of Obama’s first term, it had dropped to a level not seen since President Clinton’s first year in office.

The Woman Taken in Adultery and the question of capital punishment

How do Bible Christians reconcile support for the execution with the story of the Woman Taken in Adultery?

I recently had the experience of lecturing at Pepperdine University on the (possible) roots of Jewish liberalism in the Book of Deuteronomy and the connection it makes between the redemption from slavery in Egypt and the obligation to help the disadvantaged. The subsequent discussion reminded me of something that has puzzled me for a long time: the apparent irrelevance of those passages (especially, in the current context, the ones about not mistreating “the stranger”: i.e., immigrants) to the political commitments of many who consider themselves Bible Christians.

That, in turn, reminded me of a related puzzle, this one based on a passage from the Gospels rather than the Hebrew Bible.

Consider, if you will, John 8:1-11, the story of the Woman Taken in Adultery.

Jesus went unto the mount of Olives. And early in the morning he came again into the temple, and all the people came unto him; and he sat down, and taught them.

And the scribes and Pharisees brought unto him a woman taken in adultery; and when they had set her in the midst, they say unto him, Master, this woman was taken in adultery, in the very act. Now Moses in the law commanded us, that such should be stoned: but what sayest thou?

This they said, tempting him, that they might have to accuse him. But Jesus stooped down, and with finger wrote on the ground, as though he heard them not. So when they continued asking him, he lifted up himself, and said unto them, He that is without sin among you, let him first cast a stone at her. And again he stooped down, and wrote on the ground.

And they which heard it, being convicted by their own conscience, went out one by one, beginning at the eldest, even unto the last: and Jesus was left alone, and the woman standing in the midst.

When Jesus had lifted up himself, and saw none but the woman, he said unto her, Woman, where are those thine accusers? hath no man condemned thee? She said, No man, Lord. And Jesus said unto her, Neither do I condemn thee: go, and sin no more.

It’s a familiar story, having supplied two phrases (“casting the first stone” and “Go, and sin no more more”) that any reasonably literate English-speaker will recognize, even if unaware of their source.

And yet I have never heard it quoted in the debate on capital punishment. It seems, on the surface, to be quite decisive. The message seems to be that even if an offender has earned the death penalty under the law, no sinful human being is fit to carry it out. Is the Governor of Texas “without sin”?

So consider this an invitation to readers who know more about the Christian tradition than I do: What is the theory that reconciles this passage with support for actual imposition of the death penalty? (There seems to be more than a trace of doubt as to whether the passage was a part of the original Gospel of John, but that’s not someplace evangelical Protestants want to go.)

Footnote Some ground rules: This is not an invitation to argue about capital punishment, or about the truth or value of Christianity, or about the authority of the Bible. My question is how Christians who take the Bible as authoritative have actually dealt with the issue.

As to why death-penalty opponents don’t use this text, I think I have a good guess: it’s because, being liberals, they have swallowed the Rawlsian principle of “public reason” and thus consider the use of sacred text inadmissible in political argument. Since the words attributed to Jesus aren’t binding on non-Christians, they shouldn’t be used - says Rawls - in public discourse. Here I would add “The fool!” save for my fear of Hellfire.

Life without parole

The death sentence might be justifiable, but life without parole is hard to fathom. Still, there’s Whitey Bulger.

Unlike some of my friends, I can imagine situations where the death penalty would be justified. (That doesn’t mean I think there’s a way to make it work under U.S. legal and social conditions.)

But life-without-parole - accepted by some as a superior alternative - strikes me as almost always unjustified. Even if you agree with me that sometimes it’s possible to say “This person deserves to die,” how could you possibly say convincingly “The person this person will become in fifty years deserves to be in prison until he dies?”

That’s especially true, of course, when the Lw/oP sentence comes from a stupidly sadistic mandatory-sentencing law, of the kind we still have on the books federally and in some states, and as the result of gross failures of prosecutorial discretion.

That said, do I get to make an exception for Whitey Bulger? Though note that he was charged with racketeering rather than drug dealing, so though he drew two life sentences plus five years (a rather metaphysical verdict, if you read it literally) he didn’t actually get Lw/oP.

Footnote And no, though I can understand the politics of the situation, I can’t actually justify President Obama’s failure to commute a bunch of these sentences. If the pardon process is too opaque, then appoint three while male conservative Republican retired federal judges as an unofficial “clemency committee,” with a pre-commitment to commute any sentence for which they unanimously recommend commutation.

Being Arrested Is An Extremely Common Experience for Young Americans

Radley Balko wrote a shocking link-bait headline: 1 in 25 Americans was arrested in 2011! Balko’s statistic was derived by dividing the number of people in the country by the total number of arrests. As Balko’s readers quickly pointed out, this exaggerates the risk because many people get arrested multiple times a year. He half-retracted his claim, though he kept his screaming headline intact.

This was definitely a case where trying to sex up a public policy trend with the wrong data set and inaccurate analysis generated a less shocking result than identifying the right data set and reporting the facts. I obtained those facts from Professors Robert Brame and Shawn Bushway. They examined the cumulative risk of arrests from age 8 to 23 in a sample of 7335 National Longitudinal Survey of Youth participants. Participants reported on whether they had ever been arrested or taken into custody for illegal and delinquent offenses (excluding minor traffic violations). The period of the study was 1997 to 2008.

The focus of the research was on the cumulative risk of arrests, i.e., how likely were participants at different ages to have been arrested at least once at some point in their lives? Because not all participants completed every wave of interviews, the results could only be reported as ranges, but anywhere in those ranges represents a stunning result: By age 18, the cumulative arrest prevalence rate was between 15.9% and 26.8%. By age 23, it had risen to between 25.3% and 41.4%.

It’s a remarkably common experience for American young people to be arrested. Far more common, the study authors note, than it was in the mid-1960s when another study of this sort was conducted. Some of this of course reflects a rise in youth crime, but some of it almost certainly reflects changes in policing, including the widespread use of stop-and-frisk tactics.

The #1 date-rape drug: ethyl alcohol

Emily Yoffe is right:

Less drunkenness = fewer rapes.

Why is that controversial?

The #1 “date rape” drug is, and always has been, alcohol. Yes, it’s possible to slip another drug into a drink so the victim doesn’t know what she’s taking, but if that were eliminated 90+% of the problem would remain. Drunken women are easy victims, and current social norms encourage young women to get drunk. A would-be rapist really doesn’t need Rohypnol.

Of course the flip side of that is also true. Drunken men are much more likely to be sexually (and otherwise) aggressive, and current social norms encourage young men to get drunk; that’s a problem on top of the fact that other norms encourage their sexual (and other) aggression.

Three cheers for Emily Yoffe for being willing to write this down. At some point, as the hysteria about “drugs” recedes, maybe we can start a serious policy discussion about the drug that does more damage than all the “controlled substances” combined. The result of that discussion should be higher taxes, negative marketing, marketing limits, user-set personal quotas, and bans on alcohol sales to people convicted of alcohol-related crimes.

But starting the discussion with the simple proposition that getting trashed is a very, very bad habit wouldn’t be a bad start. And yes, part of the problem is that school-based “drug prevention” programs often fail to distinguish between drinking and getting drunk.

Footnote The editors of TPM seem to have been fooled into running a prank commentary. I suspect (or at least, I hope) that “Soraya Chemaly” is either an anti-feminist, engaged in a broad and un-funny parody of feminist analysis, or a beer-company shill doing the alcohol version of the gun lobby’s “Guns don’t kill people; people kill people” shtick.

Of course the primary moral onus for sexual assault is on the assailant; who denies it? Not Yoffe, who states it explicitly. But alcohol makes potential assailants more likely to offend and also makes potential victims softer targets. Subtract drunkenness from the equation, and there’d be much less sexual assault. (Also true, it turns out, of domestic violence.) Understanding that doesn’t mean blaming rapists less; it simply means adopting one effective means of denying them vulnerable targets.

Yoffe, as a woman writing to women, suggests that they can defend themselves by not getting sloshed in public. She’s right. “Chemaly” (or whoever borrowed her identity) suggests that men should be convinced not to commit rape. Yes, that would be nice to do, if someone knew how to do it. But “Chemaly” seems to think that telling potential victims how to protect themselves constitutes “blaming the victim.” That’s beyond dumb.

Update One theme, in the commentaries below and in the discussion of Yoffe’s essay elsewhere, is that any individual girl who doesn’t get drunk is simply pushing victimization onto someone else, without changing the total rate of victimization. That would be true if the number of potential predators was fixed and if each predator kept searching until he found a victim and then stopped. But stating those conditions makes it clear how implausible the argument is. Of course the number, distribution, and behavior of potential victims influences the number of completed crimes. Surely lots of men commit acquaintance rape who didn’t explicitly intend to do so at the beginning of the evening, and equally surely lots of men looking to “score” by fair means or foul fail to do so because they don’t encounter an adequately vulnerable target.

![Corrections in the United States_0442512_2[1]](../../wp-content/uploads/2013/07/Corrections-in-the-United-States_0442512_21.jpg)