The Democratic slogan on crime should be “Unburden the police,” specifically: fund community-based violence interruption programs; fund first-response mental health programs; eliminate traffic stops. With those things off their plates cops can focus on crime-solving/case clearance.

We shouldn’t minimize the reasons communities have for hating and fearing police practices, but we also can’t minimize the reasons those same communities have for wanting protection from crime. So reform the practices: spend less person-power on routine interference with citizens (whether pedestrian stop & frisk or traffic stop & harass) and more on solving crimes (which will be easier when people don’t suffer constant adversarial or humiliating or even fatal interactions with cops). And turn violence interruption over to community groups trained in its successful practice (like those that provided Chicago with a fairly peaceful Memorial Day weekend) and mental health crises over to professionals trained to handle those encounters.

And then use the right rhetoric! “Unburden the police” means exactly the same thing as “defund the police” but sounds pro- instead of anti-cop, anti- instead of pro-crime. “Fight crime smarter not harder.” “Build policing back better.”

Let’s stop leading with our chins on an issue where we have the right answers and our “Blue Lives Matter” opponents have nothing to offer.

Tag: crime

On mass incarceration, BS from B.S.

Political candidates make statements that do not closely track the facts. That’s a given. Sometimes it’s just fluff and spin: not creditable, but not a mortal sin, either.

Sometimes, however, a candidate makes a statement suggesting that the candidate is either being deliberately deceptive on a matter of importance or simply has no idea what he or she is talking about.

Consider, for example, this from Bernie Sanders:

… at the end of my first term, we will not have more people in jail than any other country.

That’s a very specific promise, with a timeline attached. And it is a promise that no President has the power to fulfill.

If we elide the distinction between prisons (holding people convicted of serious crimes) and jails (holding people convicted of minor crimes and people awaiting trial), it is true and important that the U.S. leads the world in incarceration. That’s a disgrace. (I seem to recall having written a book on the topic.)

We should do something about that, and there are things to do about it. A President can do some of them.

But of the 2.3 million people behind bars in this country, fewer than 10% are Federal prisoners. The rest are in state prisons and local jails. If the President were to release all of the Federal prisoners, we would still, as a country, have more prisoners than any other country. So Sen. Sanders was very specifically making a promise he has no way of keeping. Either he knows that or he does not.

And his promise to accomplish it with “education and jobs” utterly misunderstands the short-term relationships between schooling and employment on the one hand and crime and incarceration on the other.

So it sounds as if Sen. Sanders, after several decades in public office, is either utterly unserious or utterly clueless about the crime issue. Again, that’s excusable. But since he also seems to know very little about foreign policy, and much of what he thinks he knows about health care is just plain wrong, someone might want to start asking what it is he does know about, other than how to get a crowd riled up by denouncing the banksters.

Those of us supporting Hillary Clinton this year are sometimes accused of wanting to settle for political small-ball rather than sweeping change. But no matter how good Sen. Sanders’s intentions may be, he’s not going to be able to change very much for the better unless he’s willing to learn something about the way the world, and the political system, actually operate.

Learning requires both humility - the knowledge of what one does not now know - and curiosity. Sen. Sanders’s passionate conviction that he already knows the truth, and that anyone who disagrees with him must be in the pay of special interests, does not suggest that he numbers either humility or curiosity among his many virtues.

You’re welcome

Since no one else noticed the Ferguson thing…

Glenn Loury and I talked about it on Bloggingheads.

We discussed the political economy of suburban poverty, rioting and the social contract, the necessity and the difficulty of achieving police legitimacy, the incredible social harm done through the looting of small businesses that accompany urban unrest, and order maintenance as a cooperative achievement of both the citizenry and the police.

America’s most criminogenic drug

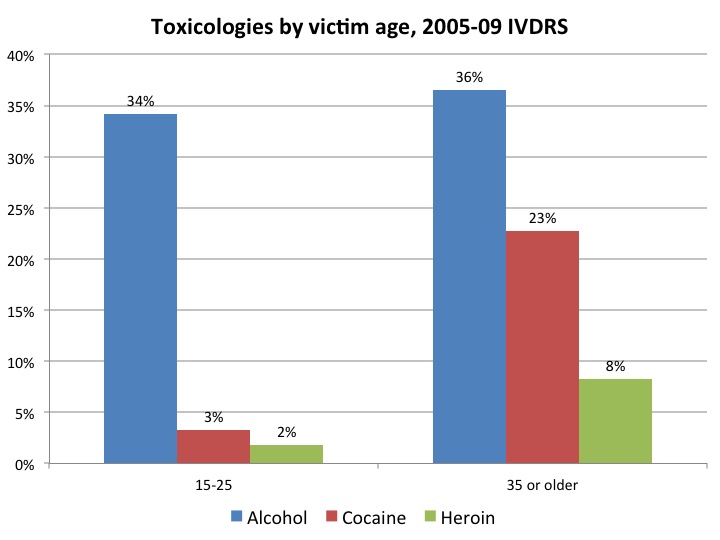

Which intoxicating substance is associated with the most lethal violence? Devotees of the Wire might presume that cocaine or maybe heroin would top the list.

Of course the correct answer, by far, is alcohol. It’s involved in more homicides than pretty much every other substance, combined. Surveys of people incarcerated for violent crimes indicate that about 40% had been drinking at the time they committed these offenses. Among those who had been drinking, average blood-alcohol levels were estimated to exceed three times the legal limit.

Aside from its role among perpetrators of violence, alcohol use is widespread among victims, too, for some of the same reasons. Recent data from the Illinois Violent Death Reporting System (IVDRS) bear out these trends. At my request, researchers at the Stanley Manne Children’s Research Institute analyzed 3,016 homicides occurring in five Illinois counties between 2005 and 2009. I find the below figures quite striking, particularly among young people. More here…

Lead and crime, continued

Lead causes crime. How much of the great crime wave and the great crime decline were lead-driven is unclear.

Yesterday I returned to banging the (Kevin) drum about the pernicious effects of environmental lead. Both a note from a reader and comments elsewhere about Kevin’s latest post suggest that an earlier post of mine had created confusion.

Here’s the note:

Mark, in your latest post, you seem to be believing the lead hypothesis for violent crime again. But here I thought you said that Phil Cook changed your mind. Are there new data that tipped you back, or is there a hole in Cook’s argument?

There are two different claims here:

- Lead causes crime, and the effect size is large.

- Decreasing lead exposure was the primary cause of the crime decline that started in 1994.

#1 is certainly true, and nothing Cook has written or said contradicts it. We have both statistical evidence at the individual level and a biological understanding of the brain functions disrupted by lead.

Cook convinced me that #2 is not true, or at least is not the whole story, because the decline happened in all cohorts while lead exposure deceased only for the younger cohorts. You can still tell plausible stories about how the young’uns drove the homicide wave of the late 1980s/early 1990s and that less violent subsequent cohorts of young’uns reduced the overall level of violence, but that’s not as simple a story. In a world of many interlinked causes and both positive and negative feedbacks, the statement “X% of the change in A was caused by a change in B” has no straightforward empirical sense.

So I’m absolutely convinced that lead is criminogenic, in addition to doing all sorts of other personal and social harm, and strongly suspect that further reductions in lead exposure (concentrating on lead in interior paint and lead in soil where children play) would yield benefits in excess of their costs, even though those costs might be in the billions of dollars per year. What’s less clear is how much of the crime increase starting in the early 1960s and the crime decrease starting in the early 1990s (and the rises and falls of crime in the rest of the developed world) should be attributed to changes in lead exposure.

The original point of yesterday’s post stands: When you hear people complaining about environmental regulation, what they’re demanding is that businesses should be allowed to poison children and other living things. No matter how often they’re wrong about that - lead, pesticides, smog, sulphur oxides, chlorofluorocarbons, estrongenic chemicals - they keep on pretending that the next identified environmental problem - global warming, for example - is just a made-up issue, and that dealing with it will tank the economy. Of course health and safety regulation can be, and is, taken to excess. But the balance-of-harms calculation isn’t really hard to do. And the demand for “corporate free speech” is simply a way of giving the perpetrators of environmental crimes a nearly invincible political advantage over the victims.

Lead and crime: a hole in the theory

Lead exposure is criminogenic at the individual level. It’s tempting to attribute the big increase in crime after 1960 and the big decrease after 1994 to getting the lead out of gasoline. But it turns out those changes were period effects, not cohort effects.

Kevin Drum, whose “Criminal Element” essay linking violence rates to lead exposure has been (as it deserves to be) extraordinarily influential, links to a BBC story in which a more-than-usually-dim criminologist explains that he disbelieves in the lead-crime link because all biological explanations of crime are outside “the mainstream” (presumably meaning “the mainstream of criminological research”). Kevin is right to say that the multiple levels of evidence for the lead-crime link (brain-imaging work, case-control studies at the individual level, studies of crime changes in neighborhoods that suffered greater and lesser increases in lead exposure after WWII and decreases in lead exposure after the mid-1970s, and cross-national studies) deserve more than a casual blow-off. It’s not, after all, as if “mainstream” criminology had a bunch of well-worked out causal theories with proven predictive power.

Like Kevin, I’ve been frustated that the evidence about lead hasn’t led to more action, if only some serious experimental work removing lead from randomly selected buildings or neighborhoods and then doing developmental measurements on the childen in the chosen areas compared to children in control areas. And I was puzzled when I heard that the hyper-sensible Phil Cook of Duke was among the skeptics.

Alas, Phil seems to have good reason to raise questions, especially about the ultra-strong claims sometimes heard about the percentage of the crime drop since 1994 attributable to changes in lead exposure. (Note that in a system with multiple positive feedbacks, the change-attribution factors needn’t sum to unity, so the claim that “the change in X accounts for 90% of the change in Y” is dubious on its face.)

Cook writes:

My skepticism about the “lead removal” explanation for the crime drop stems from the same source as my skepticism about the Donohue-Levitt explanation in terms of abortion legalization. They have an exact parallel to the previous explanations for the surge in violence of the late ’80s by John DiIulio and others. The focus in both cases is the character of the kids: the belief that during the 80s the teens were getting worse and during the ’90s they were getting better. Even a fairly casual glance at the data demonstrates that whatever the cause of the crime surge, and then the crime drop, it was not associated with particular cohorts. It was an environmental effect 10 cohorts were swept up in the crime surge simultaneously, and the drop has the same correlated pattern.

There is a natural inclination to assume that the reason the murder rate is increasing is because there are more murderers, and the reason we have fewer is that there are fewer murderers. It’s not that I rule out such explanations - I’m open to the idea of lead removal and abortion legalization - it’s just that I don’t think it explains the actual pattern of the youth violence epidemic, either up or down. More generally, my instinct is to look to the social and economic environment to explain large shifts in population outcomes.

Here’s Cook’s paper with John Laub.

Now, since youth violence surely has impacts on adult violence, finding that all the cohorts decreased their violence at the same time doesn’t quite rule out the idea that the younger cohorts were largely driving the train. And those brain-imaging, case-control, neighborhood, and cross-national results are still out there. But Cook’s objection remains a powerful one: the theory predicts that we should have seen the crime declines specifically in the birth cohorts exposed to less lead, and that’s not what we saw in fact.

I’d still like to see some experimental work to figure out how much additional lead removal would turn out to be cost-justified (with crime-reduction benefits a significant, but but not the dominant, part of the benefit story), but the simple story “Crime declined because lead declined” now has a major hole in it. That’s too bad, because attempts to find the relevant social and economic causes haven’t gotten very far. To my mind, the crime boom that started in the late 1950s or early 1960s and the crime bust that started in the mid- 1990s (and other large-scale, decades-long swings up and down in crime rates elsewhere) remain largely unexplained in retrospect, as they were entirely unpredicted in prospect.

Footnote And that, of course, is the difference between science and policy analysis on the one hand and mere advocacy on the other. Of course scientists and analysts are influenced by their values and prejudices. I don’t pretend that Jessica Reyes’s work didn’t make me happy or that Cook’s response doesn’t make me sad. The lead-crime story fits all my political prejudices, as well as my taste for simple and surprising explanations with clear policy implications. And I’ve been a loud advocate for it. But I don’t want to believe it if it isn’t true.

Glenn Loury and I discuss stuff at Bloggingheads

We hit on gun policy, terrible journalism about Chicago crime, why I harbor some human sympathy for George Zimmerman, and why Tom Wolfe would have been such a superb observer of the urban scene-if only he weren’t such a horrible novelist.

How not to write about Chicago’s crime problem

An unsympathetic outsider visits the Windy City.

If you have to write a story about Chicago’s crime problem, you couldn’t do much worse than Kevin Williamson’s “Gangsterville: How Chicago reclaimed the projects but lost the city,†on the web at the National Review.

To be sure, Williamson makes a few good points. He notes, for example, that the decline of disciplined hierarchical gangs may have brought unintended consequences. He reminds the youngsters of notorious Chicago gangsters Larry Hoover and Jeff Fort. In just about every other way, this piece illustrates much that is wrong in the way millions of Americans view the urban scene.

He notes-but variously seems to forget- that it’s not Dodge City here. Chicago homicide rates—though up roughly 20 percent between 2011 and 2012—remain a notch below levels of ten or fifteen years ago. Homicide rates are way below the levels of the early 1990s and the crack epidemic years. Non-homicide crime rates have also declined. Our homicide decline has been too slow when compared with LA or New York. Still, many cities—Baltimore, Detroit, Cleveland, Camden-would love to have Chicago’s problems or our crime rate.

Williamson’s article is filled with homespun wisdom such as the following:

The usual noises were made about gun control, and especially the flow of guns from nearby Indiana into Chicago, though nobody bothered to ask why Chicago is a war zone and Muncie isn’t.

I don’t know about Muncie, which is four hours away. People have bothered to ask about our almost-immediate neighbor: Gary, Indiana. An April 2012 Chicago magazine piece described swathes of Gary’s housing stock as “burned and cratered as if in a war zone.†Continue reading “How not to write about Chicago’s crime problem”

Concerning replication

Heraclitus said that no one can step twice into the same river. By the same token, it isn’t really possible to do the same program in two different places.

I’m in London for meetings on criminal justice organized by the Centre for Justice Innovation (the UK arm of the Center for Court Innovation) and Policy Exchange. A small meeting that ran for two hours today tried to figure out whether the coerced-sobriety approach of the South Dakota 24/7 project (the alcohol version of HOPE) could be used in Scotland, with social problems, customs, and institutional arrangements quite unlike South Dakota’s. (In particular, Scotland has no such thing as a two-day term of confinement.)

The answer seems to be that you could try to do something based on similar principles and with similar aims, but you couldn’t really do the program in its trademark style, and even if you’re convinced 24/7 works on drunk drivers in Sioux Falls you can’t be sure that the alternative version would work on drunken wife-beaters in Glasgow.

That suggests a more general reflection. Heraclitus said that no one can step twice into the same river. By the same token, it isn’t really possible to do the same program in two different places.