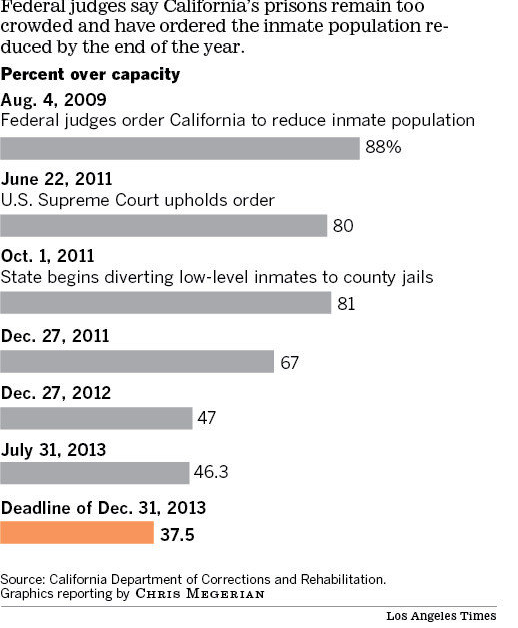

Gov. Jerry Brown has known for some time that California’s Prison Realignment was unlikely to bring overcrowding within the CDCR’s facilities in line with the SCOTUS ruling in Brown v. Plata. When Justice Kennedy’s majority opinion upheld the three-court decision requiring the CDCR to bring down overcrowding from 175% to 137.5%, the State correctly identified that relieving the pressure in the chamber could be achieved in many ways: it could build more prisons; it could invest in smart and effective probation measures; it could tinker with the sentencing rules; or it could mobilise county facilities to do jobs that were historically reserved for the state. It ultimately settled on the fourth option.

Gov. Jerry Brown has known for some time that California’s Prison Realignment was unlikely to bring overcrowding within the CDCR’s facilities in line with the SCOTUS ruling in Brown v. Plata. When Justice Kennedy’s majority opinion upheld the three-court decision requiring the CDCR to bring down overcrowding from 175% to 137.5%, the State correctly identified that relieving the pressure in the chamber could be achieved in many ways: it could build more prisons; it could invest in smart and effective probation measures; it could tinker with the sentencing rules; or it could mobilise county facilities to do jobs that were historically reserved for the state. It ultimately settled on the fourth option.

The state’s effort to transfer inmates from state facilities into county jails was a move of legal and political ingenuity. It enabled the Governor to assure citizens that he wasn’t releasing offenders, as Alito had forewarned in his dissent to Brown v. Plata, and it evaded having to raise vast amounts of money to build new prisons, thus protecting Brown’s re-election prospects for 2014.

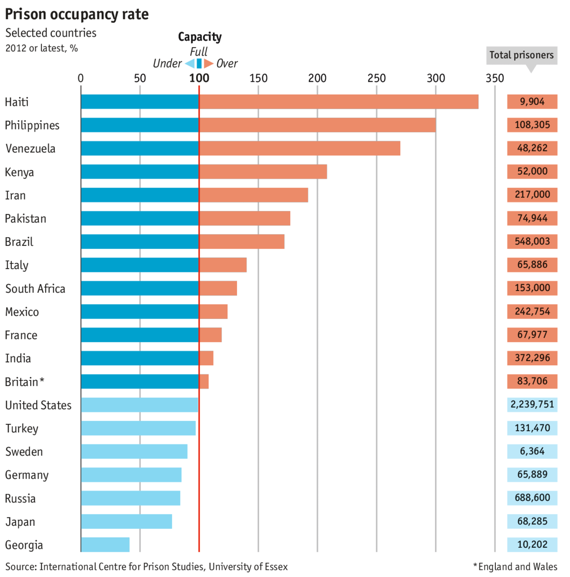

But Realignment has been, at best, playing at the margins. To be sure, the margins in California’s prison system are huge, and the effects are already visible. Indeed, the recent reductions in the US prison population have been largely spurred on by California’s recent re-arrangements. The Economist even featured a graph this week that suggested the total US ‘prison occupancy rate’ (a measure of the number of inmates relative to the number of prison beds) was below 100%, meaning within capacity. Unfortunately, a cursory search through the source material at ICPS failed to provide sufficient information with which to verify the statistic for myself, or examine any trends in the data. If true, however, I’d hazard the guess that before California’s recent Realignment, the US occupancy rate would have been in excess of 100%.

The progress made in California thus far seems to have stalled. Brown claims to have exhausted all reasonable measures to move inmates between correctional facilities within the state, and any further measure would make Alito’s nightmare of thousands of feral offenders loose on the streets a reality. According to the L.A. Times, the CDCR has displaced inmates to county jails almost to the point of rupture, and it is considering relying on imperfect facilities such as low-security detention centres, fire-fighting camps, and facilities in other states. Nonetheless, last week the Supreme Court refused to acquiesce to Brown’s assurance that the CDCR had reduced overcrowding to levels sufficient to comply with Brown v. Plata.

The progress made in California thus far seems to have stalled. Brown claims to have exhausted all reasonable measures to move inmates between correctional facilities within the state, and any further measure would make Alito’s nightmare of thousands of feral offenders loose on the streets a reality. According to the L.A. Times, the CDCR has displaced inmates to county jails almost to the point of rupture, and it is considering relying on imperfect facilities such as low-security detention centres, fire-fighting camps, and facilities in other states. Nonetheless, last week the Supreme Court refused to acquiesce to Brown’s assurance that the CDCR had reduced overcrowding to levels sufficient to comply with Brown v. Plata.

An offender release thus seems inevitable given the political realities. However, the strategy underlying the implementation of Realignment attests to Brown’s reluctance to take politically bold steps – even if those steps require surprisingly little audacity when viewed against the scientific evidence. If a large-scale release happens, in all likelihood it will begin with the elderly and the infirm. This might bring the overcrowding problem in line with Brown v. Plata.

Or it might not. In drawing attention to how California is “stubbornly behind the curve†on criminal justice and incarceration, the New York Times ran an editorial yesterday advocating the establishment of a sentencing commission and a greater focus on connecting released inmates with extant re-entry and rehabilitation services. These are sensible measures irrespective of whether Brown succeeds in reducing overcrowding by the end of the year. But to get a sense of just how conservative Brown has been in trying to relieve overcrowding, it might be instructive to look abroad:

- Italy currently has one of the worst records of prison overcrowding in Europe (the occupancy rate there is well over 140%). The Italian Senate ruled on Thursday that they will be cutting pre-trial detentions and will use alternative punishments for minor offences.

- Venezuela will place 20,000 (40% of the total prison population) of its lowest risk, minor offending inmates on conditional release.

- South Africa intends to dismiss the probation or parole sentence of 20,000 offenders, and grant pardons to a further 14,600 prisoners.

Releasing huge swaths of California’s prison population, as has been done in Venezuela, would be imprudent. But Brown’s reluctance to entertain the idea of offender releases, except as an absolute last resort, shows his inability to recognise just how modest Realignment has been.