Of course my brilliant old friend and longtime UCLA colleague Eugene Volokh is right (and Jeb Bush was also right, though tin-eared and hard-hearted).  The impulse do “do something” in the face of a bad situation, and especially after a disaster, can lead to policies that make things worse instead of better (for example, invading Iraq), and it is wiser to resist that impulse than to do something foolish. The “Yes, Minister” syllogism - “We must do something; this is something; therefore we must do this” - is not a form of reasoning that leads to good results.

That’s especially true for gun policy, because the debate heats up after a mass shooting, and mass shootings are completely atypical of gun deaths overall. The question “What would have prevented this particular disaster?” is inevitably the wrong question.

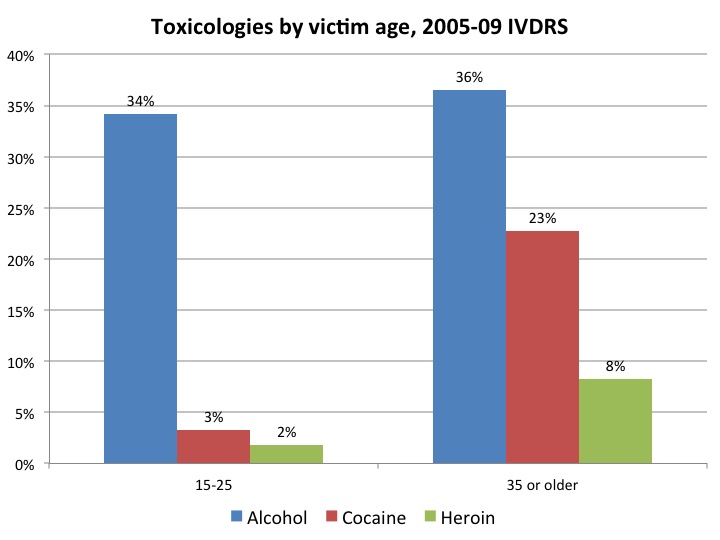

And Eugene is also right - being right in the service of really bad policy choices is one of his annoying habits - to compare guns to alcohol as two commodities whose consumption in the United States leads to the deaths of tens of thousands of people other than consumers, in addition to deaths among the consumers themselves.

But that’s where Eugene stops being right and becomes ridiculously and disastrously wrong. He assumes, falsely, that just because we’re not currently doing much to stop the violence involving guns and alcohol it must be the case that nothing useful can be done. Â In the case of guns, the cross-national statistics offer a strong hint that there’s something very wrong with policy in the United States, since no other developed country has anything like our rate of gun deaths. Our rate is three times that of Finland or Switzerland - our closest competitors among developed nations - four times that of Canada, and ten times that of Australia. That suggests we might have something to learn from their policies.

John Donohue’s recent work showing that adopting a “shall-issue” concealed-carry law correlates with future increases in homicide rates  suggests that state-level gun policies matter, though it’s hard to tell whether the results are due specifically “shall-issue” as opposed to “stand-your-ground” and other elements of the NRA policy agenda; states that loosen their gun laws are likely to do so along more than one dimension.  But even if there’s nothing positive to do, reining in the desire of Eugene’s gun-crazed allies to increase the prevalence of gun ownership and gun-carrying would be a good place to start.

One obvious positive thing to do about guns would be to tighten the rules about background checks. Right now, registered gun dealers (Federal Firearms Licensees, or FFLs) must verify that gun buyers are eligible to purchase; that’s the Brady Law background check. But about a third of all gun transfers don’t involve an FFL: they’re private sales, including sales at gun shows, or they’re gifts.

There’s no good reason not to require a check for every transfer; no doubt the gun stores would be happy to provide the service at a competitive price. Â That simple change, supported by the vast majority of voters and proposed by the Obama Administration, fits perfectly the NRA slogan that what we need is better enforcement of the laws already on the books. But in fact the NRA opposes it, and if Eugene supports it he’s keeping that support a secret. Â No one can estimate how many lives it would save, but surely that number isn’t zero.

If Eugene wants to say - as apparently Jeb wants to say - that protecting the convenience of gun owners and gun merchants is more important than saving lives, that’s his right. But to say that there are no lives to be saved, Â at reasonable cost to other goals, is simply false.

That’s even more obviously true with respect to Eugene’s comparison case, alcohol. He writes as if the only alternative to our current insanely loose alcohol policies would be a return to Prohibition, and that what we can do  about controlling alcohol-related deaths is “not much, other than trying to catch and punish alcohol abuse.â€

Nonsense. There are at least two options out there that would substantially reduce the number of people who die as a result of other people’s drinking (while also reducing the number who die, suddenly or slowly, as a result of their own drinking).

The first and most obvious (except to a libertarian) is raising alcohol taxes. When something costs more, people use less of it, especially people who use enough of it so its price matters in their personal budgets. Most of the damage from alcohol-related violence comes from heavy drinkers, not casual ones. Â So higher alcohol prices will lead to less drinking by heavy drinkers and therefore fewer drunk-driving deaths and fewer drunken homicides.

Philip J. Cook’s Paying the Tab estimates that a 10% increase in the price of drink (which could be achieved by doubling the current federal alcohol tax) would reduce all violent crime - not just alcohol-related crime, but of course including a lot of gun crime - by about 3%.  The effects on traffic fatalities are of about the same magnitude. The effects seem to be roughly linear.

So tripling the alcohol tax - which would cost the median drinker less than 20 cents a day, and which wouldn’t be nearly high enough to create a black market - would eliminate about 6% of the 13,000 murders we suffer each year, saving about 800 lives. It would also eliminate about the same proportion of 32,000 traffic fatalities, saving something more than 2000 additional lives. Â In other words, a simple change in the tax code could eliminate about one 9/11’s worth of sudden death per year.

The other straightforward approach to shrinking alcohol-related damage, including homicide, is to deter drinking by people who commit crimes under the influence. That’s the approach of South Dakota’s Sobriety 24/7, which requires people with prior DUI convictions arrested for a fresh DUI to come in twice a day for an alcohol-breath test, under the threat of a night in jail if the result isn’t 0.0.

The results are spectacular: being on the program (for an average of 90 days) reduces DUI recidivism by 50% over the next two years. Applying the program at a county level reduces auto fatalities by 12% and domestic-violence complaints by 9%. (Beau Kilmer and his colleagues at RAND are about to publish an estimate of the effect on all-cause mortality that will blow the top off everybody’s head, but that work is still under review so I can’t more than hint at the results.)

Here’s a more speculative idea, but one I’d like to see tried. A third activity that leads to lots of sudden deaths on the part of bystanders is driving. One thing we do to reduce the carnage is to forbid people to drive if they’re under the influence. Alcohol effects coordination, but it also influences anger management, impulse control, and judgment. So why do we let someome walk around armed when he’s drunk out of his gourd? The old-fashioned Western saloon had a “hang ’em here” policy; customers were expected to disarm before getting loaded. Why not enact that as law, requiring that anyone possessing a gun in public either (1) remain sober or (2) lock it and unload it? You could think of that as either a modification of gun policy or a modification of alcohol policy.

So Eugene’s comparison case is almost uniquely poorly chosen. There are some things we could do today to reduce gun violence by changing gun policy, but those effects would mostly happen slowly and can’t be estimated with much confidence. Â But there are things we could do about alcohol policy today that would reduce violent death, including violent death by firearm, predictably and measurably six months from now.

Yes, the activist impulse to “do something” can and does lead us astray. But so does the libertarian impulse to just sit there and watch people die, all in the name of limited government.