This post is mainly intended for my Brazilian family and friends, since it’s too long for a Facebook post. Others may find it a change from their local tragedies.

Imagine a big country with an unqualified populist elected as President who compares the Covid-19 virus to the flu, has accused the media of hyping the risk for underhand political motives, challenges death statistics, picks a fight with the governor of the most populous state including its largest city, talks frequently of an early return to work, and disregards social distancing rules himself? Not the USA but Brazil under Jair Bolsonaro. See also Wikipedia. Meanwhile the plague advances as desperate state governors declare uncoordinated lockdowns, and health care professionals complain of a shortage of masks and ventilators, well before any peak. Some drug kingpins are enforcing lockdown in their favela fiefdoms at gunpoint.

Imagine a big country with an unqualified populist elected as President who compares the Covid-19 virus to the flu, has accused the media of hyping the risk for underhand political motives, challenges death statistics, picks a fight with the governor of the most populous state including its largest city, talks frequently of an early return to work, and disregards social distancing rules himself? Not the USA but Brazil under Jair Bolsonaro. See also Wikipedia. Meanwhile the plague advances as desperate state governors declare uncoordinated lockdowns, and health care professionals complain of a shortage of masks and ventilators, well before any peak. Some drug kingpins are enforcing lockdown in their favela fiefdoms at gunpoint.

Remember that sickening moment on 9/11 when you realized that the collapsing skyscrapers were not from a disaster movie, but the horrifyingly real thing? That’s Brazil today.

Into this chaos step the high-minded foreign experts. On March 26, the industrious mathematical epidemiologists at Imperial College (Walker, Whittaker et multi) released their Report 12 (pdf) extending their scenarios from the UK and the USA, as in report 9, to 102 countries. The O Globo newspaper got hold of the data spreadsheet (xls here; extract for Brazil only by me here) and published what looks like an accurate summary. Judging by the Facebook posts of my Brazilian acquaintances, this was greeted with widespread incredulity. Let me try to persuade them to take it seriously.

To recap, the Imperial team modelled three main mitigation scenarios for this country of 212 million inhabitants. They put in various values of R from 2.4 to 3.3, and assumed social distancing would be about 40% effective . They define R thus: “R0 : Basic Reproduction number (average number of secondary infections by a typical infection in an unconstrained epidemic and wholly susceptible population).”

A – no mitigation at all:

- total ultimate infections 183m – 188m

- total deaths 908,000 – 1,152,000,

- total critical hospitalizations 1,466,000

- peak critical bed demand 470,000

B – social distancing (40%) only for the elderly:

- total ultimate infections 92m- 121m

- total deaths 271,000 – 530,000

- total critical hospitalizations 359,000 – 703,000

C - social distancing (40%) for the entire population:

- total ultimate infections 95m- 122m

- total deaths 452,000 - 627,000

- total critical hospitalizations 600,000 – 831,000

What to think of this?

1. It’s state-of-the-art professional modelling. The parameters are put in from the latest data, especially Chinese. Put in different parameters, and you get different results. But you can’t just make up your own parameters, you need a reason. A bigger number of asymptomatic carriers? Maybe; it lowers the total of infections in Scenario A, as you hit herd immunity sooner, but the higher pace of infection exacerbates the peak load on hospitals. Wishful thinking in the Trump/Bolsonaro style does not hack it.

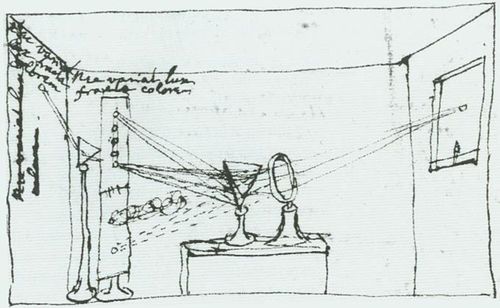

2. The least reliable scenario is A, the disaster one in which no action is taken. This won’t happen, anywhere, for two opposite reasons. One: even if central governments fail, as in the USA, Mexico and Brazil, lower levels of government step in – less effectively, but they will act. If the worst comes to the worst, people will just self-isolate, as Isaac Newton did in the London bubonic plague of 1665. (Incidentally, this is why the “economy vs. public health” opposition is a false one. The economy tanks sooner or later, whatever the government does.) Two: a reason, this time on the bad side, for distrusting scenario A is that it does not allow for hospital collapse, which would be inevitable. Death rates would rocket, unpredictably. The model is benchmarked on the Chinese health care system which never faced such extreme loads.

3. The key conclusion of the Imperial reports is that mitigation isn’t enough, you have to go for energetic suppression to keep the health system from collapsing. Even the lowest Imperial mitigation scenario has over 2m hospitalisations in Brazil, 360,000 of them critical ones. Brazil has 415,000 hospital beds, just adequate for normal times. Any mitigation scenario leads to hospital collapse. Unfortunately they do not offer suppression scenarios, impossible for so many countries at once. So the Brazilian government has to put some work into this to avoid the catastrophe.

Stepping outside the report, there are now plenty of examples of successful suppression strategies.

Gold medal: Taiwan, silver medal: South Korea. These have not SFIK relied on fancy models at all but on the trusty Epidemics 101 playbook: test, track, isolate. The playbook was it seems first worked out for animal diseases before WWI. The part about “slaughter all the infected animals, dump the carcasses in a big pit, and burn the animal sheds” has been toned down for humans, but the take-no-prisoners attitude survives. One quarantine violator in Taiwan was fined $33,000. The Vice-President is an epidemiologist. I doubt if Brazil has the administrative capacity or social cohesion for this, and anyway it’s too late.

Second best is Europe. After a late start, most countries adopted strict lockdowns to drive R below 1 quickly. They are working. In Spain where I live, a state of emergency and national lockdown was declared on March 15. New deaths peaked on April 1. Cumulative deaths on that date stood at 10,003. Assume the curve is symmetrical, and total deaths will end up around 20,000. Scale that to Brazil, and you would get 99,000.

That would be a decent second-best outcome starting from now (cases 20,247, deaths 1,090). I’m afraid I don’t believe it. Spain has a competent and rational government and civil service, a first-world healthcare system, and a surprisingly deep reserve of social solidarity in spite of political divisions. Brazil has much lower levels of trust in government, very high inequality, and a healthcare system overstretched in normal times. In addition to these structural handicaps, it has, like the USA, unwisely elected an erratic and irrational President incapable of offering the example of steadiness and discipline required by the situation*, The country will IMHO be lucky to escape with under 200,000 deaths. It could easily be worse.

* Epidemic management is a Roman dictatorship of public health experts. What political leaders have to do is hand over the keys and make frequent sober and statesmanlike statements. A good number of quite ordinary politicians have shown themselves up to this: Xi Jinping, Moon Jae-in, Merkel, Conte, Sanchez, Cuomo, Newsom, even Matt Hancock, the previously unimpressive British Health Secretary. The failures are striking: Trump, Obrador, Bolsonaro, Abe.

Imagine a big country with an unqualified populist elected as President who compares the Covid-19 virus to the flu, has accused the media of hyping the risk for underhand political motives, challenges death statistics, picks a fight with the governor of the most populous state including its largest city, talks frequently of an early return to work, and disregards social distancing rules himself? Not the USA but Brazil under

Imagine a big country with an unqualified populist elected as President who compares the Covid-19 virus to the flu, has accused the media of hyping the risk for underhand political motives, challenges death statistics, picks a fight with the governor of the most populous state including its largest city, talks frequently of an early return to work, and disregards social distancing rules himself? Not the USA but Brazil under

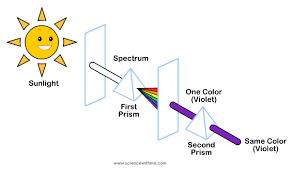

You all know the story in outline. In 1665 the bubonic plague that devastated London reached Cambridge, where Newton was a freshly minted B.A. (Cantab.) He fled to his uncle’s farm in Lincolnshire. This is now called

You all know the story in outline. In 1665 the bubonic plague that devastated London reached Cambridge, where Newton was a freshly minted B.A. (Cantab.) He fled to his uncle’s farm in Lincolnshire. This is now called