I’m a fan of George Orwell. I think one of the most important pieces of writing in the English language, for example, is his set of rules for how to make the perfect cup of tea. In fact, I sometimes wonder whether people can really make a cup of tea, and therefore participate in civilised society, without following those rules; I often ungraciously request that my friends read Orwell’s piece before I permit them to hand me a brew.

Because of this general affinity for Orwell’s work, it’s always with some sadness that I look over his prescriptions for what constitutes good writing. He distils these into six rules:

- Never use a metaphor, simile, or other figure of speech which you are used to seeing in print.

- Never use a long word where a short one will do.

- If it is possible to cut a word out, always cut it out.

- Never use the passive where you can use the active.

- Never use a foreign phrase, a scientific word, or a jargon word if you can think of an everyday English equivalent.

- Break any of these rules sooner than say anything outright barbarous.

They cause me sadness because I know full well that I violate rules one through five fairly regularly – a violation that I justify by appealing to rule six. I recognise that my own style of writing – my modus scribendi – is all-too-often characterised by florid and pleonastic writing. ↠There you have it: twenty-one words in a sentence that would make Orwell spill his impeccably brewed tea all over his morning copy of Pravda. Cliché? Check. Aureate prose? Unquestionably. Prolixity? Naturally. Passive voice? Colour me checked. Argot? Affirmative. And yet, aside from being inelegantly constructed, I don’t see much of a problem with it. It conveys the point clearly, albeit pretentiously.

Ed Smith’s last column from the New Statesman argued that Orwell’s rules have been co-opted and deployed for precisely the nefarious purposes Orwell had hoped to prevent:

Orwell argues that “the great enemy of clear language is insincerity. When there is a gap between one’s real and one’s declared aims, one turns as it were instinctively to long words.â€

I suspect the opposite is now true. When politicians or corporate front men have to bridge a gap between what they are saying and what they know to be true, their preferred technique is to convey authenticity by speaking with misleading simplicity. The ubiquitous injunction “Let’s be clearâ€, followed by a list of five bogus bullet-points, is a much more common refuge than the Latinate diction and Byzantine sentence structure that Orwell deplored.

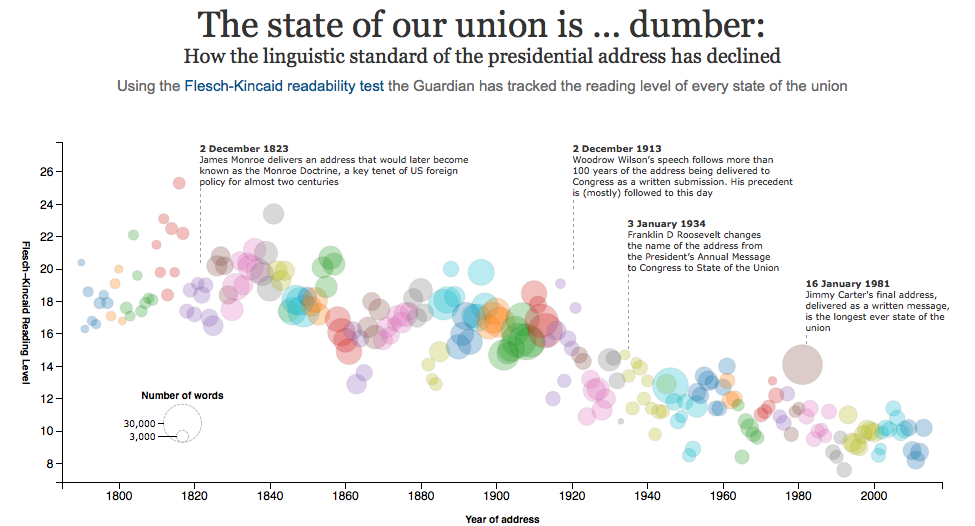

The argument seems plausible to me. Indeed, the Guardian has a lovely infographic that illustrates how SOTU speeches have adopted increasingly simpler vocabulary and syntax over time. You can decide for yourself whether this has accompanied more political duplicity, as Smith argues.

I enjoyed Smith’s post not just because I think the argument seems accurate. It’s because I’d like to think that in my own case, grandiloquent writing isn’t really the problem. Orwell’s concern was not with the choice of words (a stylistic concern); it was with the way words can be used to manipulate thoughts (a substantive concern). Hence, the dispositive sixth rule.

My take-away from Orwell’s writing rules, then, is that the sixth is the only true ‘rule,’ as it is the only one with substantive content – not to write anything barbarous. The preceding five ‘rules’ aren’t really rules at all. They’re more like suggestions, and Orwell didn’t have much of a bee in his bonnet for those.

Oops – a cliché. Damn that pesky first rule…

I used to use cliches like they were going out of style, but now I wouldn’t touch one with a ten foot pole.

Go thou and devour Language Log on Orwell (one sample here). Orwell’s distinctively persuasive style gives his prescriptions an aura they don’t deserve.

Sorry, link is http://languagelog.ldc.upenn.edu/nll/?p=992.

Is the Fleisch-Kincaid Readability score really an appropriate metric for a speech?

I suppose that is arguable, but … the F-K index penalizes long (in terms of words) sentences and long (in terms of syllables) words. Long words are likely to be argot, which justifies a penalty in the spoken word. Long sentences are difficult to parse, and arguably more difficult in speech than in writing (because you can’t go back to figure what that subordinate clause is subordinate to, etc.)

As a crude measure, I don’t have too much of a problem with the idea. The F-K index itself is a fairly crude measure of readability.

I wasn’t surprised to see a downward kink in the early 1860’s. Abe Lincoln, for sure.

I pity those writers who engage in pretentious or unnecessarily and exaggeratedly elaborate formulations.

I’m torn on these. I love their emphasis on clear thought. But their fundamentalism worries me. There are many kinds of good writing, and sometimes - especially in the Internet age, where boundaries between informal and formal blur - clarity and economy can sacrifice naturalism and human flavor. Just like a cheeseburger hits the right spot, or a pop confection balms the ear, a written cliche or passive phrasing can be a form of intellectual diplomacy between the heart and mind. This doesn’t argue for bad writing, or bad burgers, but it does argue for a more expansive, maybe “tolerant” view of language.

Isn’t a “pop confection” some kind of dessert?

Forget about writing, what about the tea? Only two tea rules are ironclad — teapot to the kettle and loose tea only. The rest is just taste prejudice. If I can’t trust the man’s judgment about tea, how can I trust his equally arbitrary rules on writing?

Orwell used to be a hero, now he’s just another schlub. Damn.

(I always follow rules one, two, three, and five anyway. Always have.)

Here’s another: lemon or milk, but not both.

I go by Charles Laughton’s ad-libbed tea advice in Ruggles of Red Gap

https://thesamefacts.com/2012/07/popular-culture/film-popular-culture/weekend-film-recommendation-ruggles-of-red-gap/

The only relevant bits of Orwell’s tea advice are: brew it strong, brew it hot, and don’t add sugar. The rest reeks of colonialism and thin milk.

No! This reeks of taste prejudice. You brew it as strong as you want and add sugar if you prefer a little sweetener — don’t try to make people like what you like! We are not all the same, we do not all taste the same (you know what I mean). Chacun and all that.

Rachelrachel is right, though — lemon and milk cannot co-exist in the same space.

“The secret of success is sincerity. Once you can fake that, you’ve got it made.” (Variously phrased and variously attributed.)

Orwell was focused mostly on political speech in a time and place of high jargon and high-flying abstraction- just how readable *are* those 1930s polemics among Stalinists, Trotskyists, Fascists, and Nazis?

Today, though, we live in a time and place dominated by the speech of high consumerism. By its nature it can never be sincere, since its truly sincere (and nicest) form would be something like “we want to transfer to you the least we possibly can for the most money we can possibly get from you.” So its practitioners have turned to fake sincerity, or fantastic irony, or outright fantasy, or some other form of disguise. Political speech, like management speech, has inevitably followed, intended as both are to achieve transaction and exchange on similar terms.

Simplicity by itself doesn’t signify much in our conditions, so I’d have to agree with the snippet from Smith. Conveying thought in a way that readers connect with seems like an appropriate rule for our circumstances.

karl - Orwell’s preferred tea is the sort that you gulp down at an early breakfast before heading out to your day’s work: strong, hot, bitter, and highly caffeinated. That’s why he prefers India tea over China tea:

“Most black tea exported to the West is from India and the Camellia assamica plant from which Indian tea is made produces higher levels of caffeine than from the Camellia sinensis variety that is used for Chinese teas.” http://www.thechineseteashop.com/tea-health.html

And his rules are designed to produce as intense and hot a brew as possible. Because you’re in a hurry, you can cool it with a drop of thin milk in order not to burn your tongue, but even then only just a drop (tea first, so you can regulate the amount of milk).

All well and good, that. But this makes his tea-drinking seem strictly utilitarian even as his rules pull a straitjacket over differing tastes. It sounds so… Orwellian.

The biggest problem with this tempest in a teapot is that it takes one of Orwell’s essays so far out of context that it’s shrieking of loneliness. If one reads “Politics and the English Language” along with “Why I Write” and “Inside the Whale,” a rather different picture emerges; now throw in Orwell’s attack on oversimplification of speech (the Ingsoc of 1984) and see if reading “Politics and the English Language” as a screed to simplify at all costs makes sense.

Orwell’s disagreement was with (mis)use of language to deceive instead of to enlighten. That’s the whole point of Rule 6. But then, if we remember that the university-educated Pythons knew full well that there is no Rule 6…

Well said. The given six rules are very handy tips for writing. Orwell's rules of writing are appreciated. Writing skill is an art and each and every art is backed by an artiest like George Orwell. This rules will be effective in our writing.

To know more please visit how to format a paper