Codfish from the waters off New England was once the cheapest protein in the world; salted, it went everywhere in the Mediterranean and Caribbean, where poor people figured out how to make it palatable and invented all the bacalhau/bacalao/merluzzo dishes that now appear as gourmet specials on menus. Now, not so much.

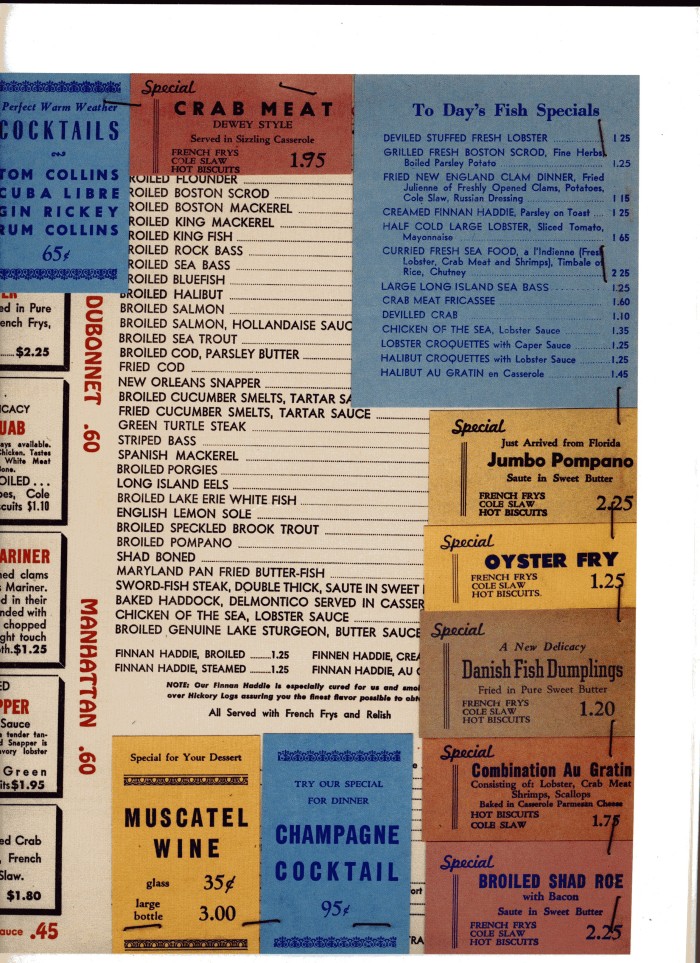

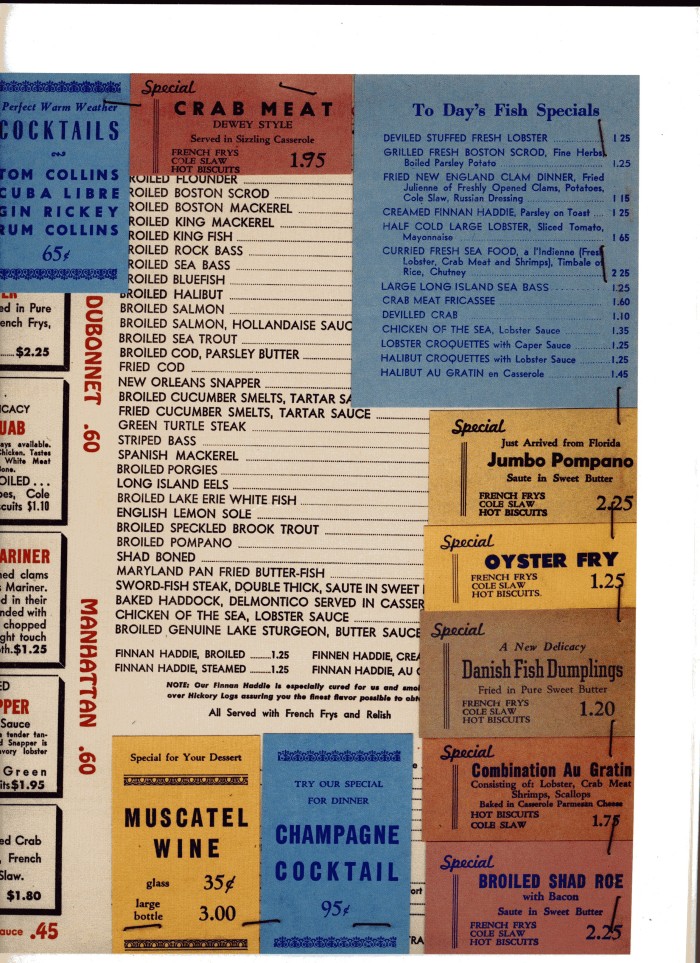

A 1951 seafood restaurant menu looked like this:

Seen finan haddie on any menus lately? Real Gulf red snapper? Any other good-tasting fish except salmon? There was no bluefish at Legal Seafoods this summer, but there’s always farmed tilapia; it tastes like sticking your tongue out the window, but you can pour all sorts of spicy sauces on it and it is technically fish. We’re pretty well down the yummy scale in the ocean, to orange roughy, for example, and “Chilean Seabass”, tasteless, coarse creatures you can try to save with seasoning. But we’ve cleaned even those out to the point that they’re both in trouble (this page just brings me to tears, as a planet resident and a diner both.

When I worked in the Massachusetts Environmental Affairs Office, the state and the feds were trying to get the Gloucester fishermen to understand what was happening to them. It was tough, and quite heartbreaking: “There will always be fish in the sea, what we need is low-interest loans to buy bigger boats with better electronics, and to stop making rules about how many days we can fish, and stop sending these pointy-head professors who don’t know a purse seine from a sow’s ear to lecture us. Look, my grandfather was a fisherman, and my father and all three uncles, and my two brothers and I: all fishermen, it’s what we do, it’s who we are.” The devastation of the sea floor occasioned by dragging a bottom trawl across it is invisible, while a culture and tradition of generations commits unintentional suicide, and on the high seas in factory ships, it’s just business.

You don’t expect Exxon to leave oil in the ground, do you?

Author: Michael O'Hare

Professor of Public Policy at the Goldman School of Public Policy, University of California, Berkeley, Michael O'Hare was raised in New York City and trained at Harvard as an architect and structural engineer. Diverted from an honest career designing buildings by the offer of a job in which he could think about anything he wanted to and spend his time with very smart and curious young people, he fell among economists and such like, and continues to benefit from their generosity with on-the-job social science training.

He has followed the process and principles of design into "nonphysical environments" such as production processes in organizations, regulation, and information management and published a variety of research in environmental policy, government policy towards the arts, and management, with special interests in energy, facility siting, information and perceptions in public choice and work environments, and policy design. His current research is focused on transportation biofuels and their effects on global land use, food security, and international trade; regulatory policy in the face of scientific uncertainty; and, after a three-decade hiatus, on NIMBY conflicts afflicting high speed rail right-of-way and nuclear waste disposal sites. He is also a regular writer on pedagogy, especially teaching in professional education, and co-edited the "Curriculum and Case Notes" section of the Journal of Policy Analysis and Management.

Between faculty appointments at the MIT Department of Urban Studies and Planning and the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard, he was director of policy analysis at the Massachusetts Executive Office of Environmental Affairs. He has had visiting appointments at Università Bocconi in Milan and the National University of Singapore and teaches regularly in the Goldman School's executive (mid-career) programs.

At GSPP, O'Hare has taught a studio course in Program and Policy Design, Arts and Cultural Policy, Public Management, the pedagogy course for graduate student instructors, Quantitative Methods, Environmental Policy, and the introduction to public policy for its undergraduate minor, which he supervises. Generally, he considers himself the school's resident expert in any subject in which there is no such thing as real expertise (a recent project concerned the governance and design of California county fairs), but is secure in the distinction of being the only faculty member with a metal lathe in his basement and a 4×5 Ebony view camera. At the moment, he would rather be making something with his hands than writing this blurb.

View all posts by Michael O'Hare

I've read that they have gotten a lot better at preserving fisheries within US EEZ waters. It came too late to save the fisheries off New England, but we might be able to save many others.

That said, it doesn't do the fish who lived outside of the EEZ's of nations willing to protect them much good, and especially not the fish who get hit by those horrific trawling nets.

It's even worse in Europe. The fisheries ministers go to Brussels every year, hear the expert advice that quotas must be cut hard, and ignore it. They go home proudly saying they have "defended our fishermen". You have seen the fishing port here in Caleta de Vélez, built with European money, full of large boats, which replaced the dories that used to be pulled up on the beach. The continental shelf is about 2 km wide here and the sustainable catch small. Almost all the full-sized fish on menus is farmed.

One ray of hope is provided by the massive offshore wind farms in the North Sea. These are incompatible with industrial fishing, especially trawling, so the farms become de facto marine conservation areas.

Your depiction of fishermen attitudes in New England is historically accurate and contributed greatly to the decline of major fish stocks like cod. However, the picture has changed dramatically in recent years in the US. New England now has a complex and adaptive system of closed areas and much tighter restrictions on catch effort and levels. In Alaska, a real model of effective fisheries management, major fisheries have never fought against scientific recommendations on catch limits. Around the country, fishermen are actively engaged with both academic and government scientists on new gear designs and fishing methods to reduce destructive bycatch and habitat impacts. All is certainly not sweetness and light, and many problems certainly remain, but attitudes in US fisheries are not quite as blind as the ones depicted in your post. It's been a long time since ads in fishing magazines for sonar systems said, "Catch the last sardine!"

Love the graphic!

It's not just overfishing. In Baltimore, there's an area called "Herring Run." At one time, the actual stream was stocked with shad which is actually a type of herring. No more due to pollution.

In the case of cod, it's not just the overfishing of cod, but also the overfishing of smaller fish (cod being a top of the food chain predator) and the change in the chemistry of the oceans due to CO2 buildup which reduces activity throughout the food chain.

I agree like crazy with your overall point, but there is wild haddock now rated as sustainable by the entities that rate such things. I think you don’t find finnan haddie more because it fell out of fashion than that the haddock it’s made from aren’t available. Here in the northeast U.S., Spence & Co. produce what they call “findon haddock”, supposedly from sustainable fisheries, which shows up in some markets in Washington, where I live. It’s very good, but you won’t find it on restaurant menus.

I query the timetable about cooking with salt cod. It was the mainstay of the Viking economy, and they still salt cod in the Lofoten Islands. The Breton and Cornish fishermen who sailed to the Grand Banks after the Cabots were supplying a large existing market.

Well at least in the Pacific Northwest we got a good sockeye salmon run every four years.