Takeaway message from the People’s Climate March: negative externalities should be taxed (or, if that’s impossible, regulated).

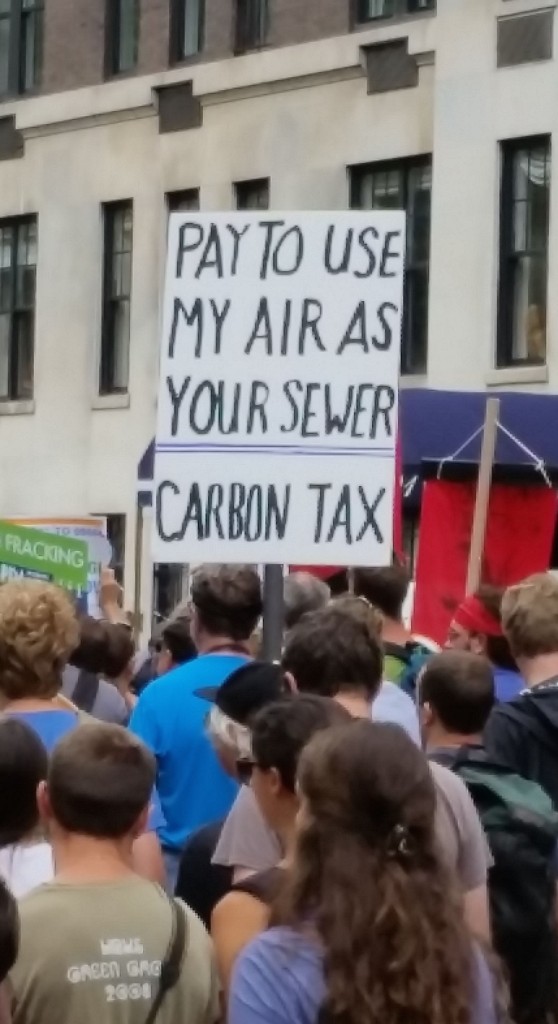

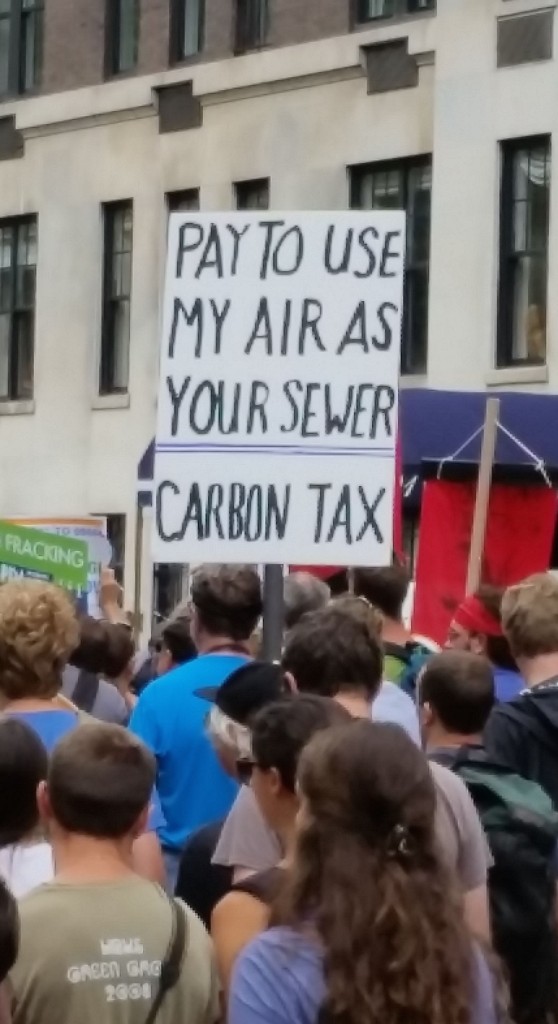

There were lots of great signs at the People’s Climate March yesterday. But for RBC readers, I’ll showcase this one:

I don’t know who’s responsible for popularizing the term “carbon pollution.” But it’s the rare political catchphrase that’s both tremendously effective and perfectly accurate. There was plenty of idealism (and of course a bit of wackiness) at the march. But at root, the core message is Micro 101:

I don’t know who’s responsible for popularizing the term “carbon pollution.” But it’s the rare political catchphrase that’s both tremendously effective and perfectly accurate. There was plenty of idealism (and of course a bit of wackiness) at the march. But at root, the core message is Micro 101:

Negative externalities should be taxed. And as a—poor, but politically necessary—second choice, they should be regulated.

Author: Andrew Sabl

Andrew Sabl, a political theorist, is Associate Professor of Political Science at the University of Toronto. He is the author of Ruling Passions: Political Offices and Democratic Ethics and Hume’s Politics: Coordination and Crisis in the History of England, both from Princeton University Press. His research interests include political ethics, liberal and democratic theory, toleration, the work of David Hume, and the realist school of contemporary political thought. He is currently finishing a book for Harvard University Press titled The Uses of Hypocrisy: An Essay on Toleration. He divides his time between Toronto and Brooklyn.

View all posts by Andrew Sabl

I don’t know who’s responsible for popularizing the term “carbon pollution.” But it’s the rare political catchphrase that’s both tremendously effective and perfectly accurate. There was plenty of idealism (and of course a bit of wackiness) at the march. But at root, the core message is Micro 101:

I don’t know who’s responsible for popularizing the term “carbon pollution.” But it’s the rare political catchphrase that’s both tremendously effective and perfectly accurate. There was plenty of idealism (and of course a bit of wackiness) at the march. But at root, the core message is Micro 101:

"Pay to use our air as your sewer" would have been better.

Not really. As written, it is more personal, and conveys outrage. The sign-holder isn't trying to speak for anyone else. When someone sits down next to me and starts smoking, I don't complain that it might bother other people.

It was probably "my" to appeal to libertarians (who don't acknowledge the existence of the first-person plural, but do get embarrassed if one compares a negative externality to a tort for which someone ought to be able to sue for damages).

I think you have it backwards. We should primarily regulate to prohibit socially undesirable or destructive activities regardless of whether there is a profit remaining after pricing in the involuntary costs that have been inflicted on other people. Not everything important to a society can be reduced to its economic value.

You have it backwards. If you define the price that must be paid as the social cost, the social and economic costs become the same. In the case of carbon, you figure out how much carbon the atmosphere can absorb and then set the tax at a level that ensures that it's inefficient to emit any more than that. That amount won't be known precisely so it's best to err on charging too much rather than too little but as time passes you can get more precision.

My point is that the needs and interests of society as a whole should be paramount. Obviously, I agree that the kinds of external costs you are discussing should generally be priced into products and activities, rather than be foisted off upon the public. Sometimes this can be done by a tax but sometimes an activity should be regulated or proscribed regardless of its profitability.

What I objected to was the idea that people would have a license to engaged in harmful activity, so long as they were prepared to bear the external costs. An example would be Ford deciding to sell Pintos even after learning that the fuel tanks were defective. Ford's bean counters correctly calculated that it would be more profitable to allow people to be killed or horribly maimed and then deal with the external costs, than to recall the defective cars. My calculus of values says that knowingly selling defective products is unacceptable even if doing so would be profitable even after paying the external costs.

It's a minor quibble but one that needs to be addressed.

I think this depends on how you define the external costs. Ford's calculations, for example, were based on the notion that not enough people would sue to make a serious dent, and that not enough of those would win large damage awards. It was only because of the imposition of a huge punitive-damage award (of a size that would be unlawful today, thanks to a business-friendly supreme court) that their calculation turned out wrong. But even that enormous cost didn't get anywhere near the total externalities in the case.

If the polluter or other tortfeasor can make the injured parties completely whole for their injuries and still produce a profit, that's OK with me. As long as they actually do so, and the decision about what constitutes making someone completely whole is in the hands of the injured parties. (And in a sense that's what we do with things like recycling fees)

If the polluter or other tortfeasor can make the injured parties completely whole for their injuries and still produce a profit, that's OK with me.

Well, sort of. The trouble is we have only some not-very-good ways to compensate people for injury, disease, or death caused by the tortfeasor. In addition we have the problem of bankruptcy.

Isn't the poster Coase as much as Pigou? A Coasian right to clean air would, as the man said ,generate the same result as the tax, assuming can-openers all the way down. Mind you, we have the reverse situation, with the emitters conceded a property right to pollute. With a different set of assumed can-openers, the victims can band together to bribe the polluters to stop. But it's much, much cheaper for the peasants to buy some pitchforks.

One thing I've always found interesting about the Coase formulation is that "realists" will almost always complain about the possibility that if you assign ownership to the folk who want to keep their air clean, some crazy holdout will set a price that's way too high for a would-be polluter to pay and still make a healthy profit. No one generally seems to worry about the problem that some crazy holdout polluter will set a price too high for the obligate oxygen-breathers to pay.

And what, no torches to go along with the pitchforks? They could be made from renewable fuel.

Organic rope is sustainable and does the job. Sadly, modern lamp-posts are no good. Mobs need the old cast-iron variety as put up for gas, or the modern retro versions you find in yuppie pedestrian precincts.

The KrugMan has pointed out that coal regulation isn't hard to do as a regulatory policy (concentrated industry, not many players to watch, cheating very difficult), so to that extent regulation is a close second as opposed to a distant second choice.