“They want to be miners, but their jobs have been taken away. And we’re going to bring them back, folks.” - candidate Donald Trump on August 10, 2016, with similar statements on many other occasions.

In contrast, the Trump Administration action on this promise has been negligible. One regulation on water pollution from mines was reversed (idem). A proposal to subsidise coal on grounds of “grid resilience” was shot down in flames by a unanimous FERC, the majority of whose members are Trump appointees.

There’s been talk of a new plan using emergency powers and an entirely different and equally specious claim of national security, but the Deep State (i.e. Trump officials who still have two working neurones) have sidelined it.

Trump has appointed a key author of Plan A, Bernard McNamee, to FERC – but there is already a serious legal challenge to force him to recuse himself from taking part in decisions on his own proposals.

Meanwhile, the industry has continued to operate under Obama’s rules. Production actually increased a little in 2017, but this was entirely due to a temporary spike in Chinese imports. It fell slightly in 2018, tracking the slow decline in domestic demand. Jobs are holding up pretty well. At first sight, Trump can plausibly claim at least to have stopped the rot.

He has not. The first bad sign is an acceleration in closures of coal generating plants, an equal record 15 GW in 2018. Chart from IEEFA:

It doesn’t look too bad for the years ahead, does it? But in fact the firmly announced closures are the tip of a Titanic iceberg. There is much, much worse to come.

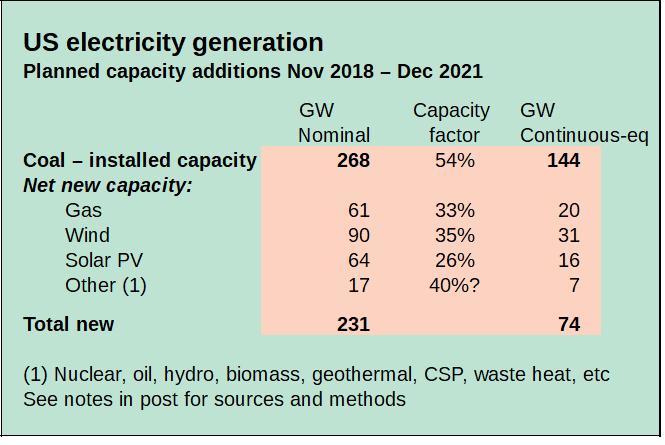

Christian Roselund at PV Magazine has a well-documented report on the excellent prospects for US utility solar. He includes a table from a FERC staff report in December 2018 (pdf, page 5) on planned additions to the US generating fleet by November 2021, and planned retirements. The full table is cluttered up by all the categories that don’t make much difference. Here’s my simplified version that focuses on the four main players: coal, gas, solar PV, and wind. Technical notes at the end.

Electricity demand in the USA is flat. The generating sources are fighting for shares of a static cake. With negligible marginal costs, the new wind and solar capacity will be higher up the merit order that determines despatch. That means their output will replace that from coal practically one-for-one. The same holds for the combined-cycle gas turbines, the Other grab-bag, and the invisible rooftop solar. The peaker gas turbines will complement wind and solar and their substitution effect will be less. The swings and roundabouts roughly cancel out, so the raw table is a pretty good basis for a forecast.

The overall picture is that the 251 GW of net new non-coal capacity will replace 51% of the existing coal fleet by 2021, or 138 GW nominal. Knock off 8 GW for the EIA’s optimistic 0.1% demand growth and we still have 130 GW surplus. That’s 43 GW 46 GW for each of the next three years. Utilities will have no reason to keep the capacity open, let alone buy coal they can’t burn. They will cancel their supply contracts and close the power stations. [Update: correction on electricity demand growth at end]

But wait. The same FERC table only gives planned coal retirements as 16.2 GW, a small fraction of my 130 GW. Both can’t be right. Which will give?

You would expect utilities to have consistent plans individually. The reason they collectively don’t is that the US electric system no longer runs on the old model of silo state monopolies, though it still holds sway in much of the South and Southwest. Most of the country has a muddled and partial version of the Thatcher three-tier model: a grid run by RTOs and ISOs, some regional (PJM, MISO), others in single big states (CAISO in California, NYISO in New York, ERCOT in Texas); a host of local distribution monopolies; and a different host of more or less competitive generators.

The last group now includes the developers or residual owners of wind and solar farms, who sell to distribution utilities through long-term PPAs or on the spot market, or direct to large corporate customers like Google through more PPAs (the last market has been booming). The surviving silo utilities combine the distribution and generation roles, and in particular own many of the coal plants. There is no longer any reason why the plans of all the generating companies taken together should be consistent, and in the coming years the new build and closure plans diverge wildly.

One of two things must give. Either developers will be forced to scale back their planned new capacity or the coal closure rate will shoot up.

I can’t see the former happening. It’s possible on paper that the Trump Administration may finally get its act together, formulate a very big and workable coal rescue plan, and get it adopted by FERC and state utility regulators. The plan must involve a very large subsidy to coal, paid for by a rise in rates paid by utility customers, both businesses and voters. It makes no difference how this is achieved, whether by cash payments, direct orders to utilities to break their contracts, or taking an axe to the merit order system that controls despatch priority. The subsidy and its costs cannot be concealed.

So far corporate Republicans, other than a handful of coal company executives, have shown no stomach for this very unpopular fight. The utility, gas, and renewable lobbies hugely outgun the coalmen. Some utilities, like Xcel in Colorado, have started waving the green flag. This won’t change. My prediction is that FERC will dither and come up with cosmetic coal-friendly reforms at most.

It is also conceivable that utilities may change their minds without coercion. On the upside, wind and solar farms can be put up in 18 months, so an acceleration in 2021 is technically possible. Earlier looks unlikely. The downside risk is that the boom will run into supply chain bottlenecks; this may already be happening with wind. The holdups could cut the actual installation rates quite significantly – but not enough to change the overall pattern.

Short take: it is highly probable that demand for coal will fall by the order of magnitude implied by the FERC data. My prediction is that the pace of closures, and the loss of mining jobs, will roughly triple. The rate of decline will rise to about 15% a year. Roselund and FERC do not provide any data on the timing of the changes, but it’s a reasonable supposition that the pace will rise over time. Still, the collapse must be very evident by the November 2020 elections.

The difference between Barack Obama’s “war on coal” and Donald Trump’s is that Trump’s war by inaction is three times as destructive.

PS. There is one simple policy change that would slowdown the coal collapse, and could secure bipartisan support in Congress. It’s to extend the sunsetting ITC and PTC tax credits for wind and solar for another decade or indefinitely. Developers of farms of both types would heave a sigh of relief at the end of artificial deadlines, and stretch out their plans over a more manageable period. The job losses in coal would be reduced in parallel. Of course, all this does is to buy time: but the election horizon is 2020, and mining job losses in Appalachia could be electorally important.

Trump should go for this but won’t. It would give an ideological win to Ms Ocasio-Cortez and other enemies; it would be anathema to the Kochs and other supporters in the gas industry, as it tilts the coming battle between gas and renewables in the latter’s favour; it requires negotiating with Democrats in Congress, which Trump seems incapable of doing; and it concedes the value of wind turbines, which he hates.

[Update 13 January: Correction on electricity demand growth. The EIA’s forecast was 0.9% a year, almost 1%, not my typo of 0.1%. This would translate to 4.5 GW continuous-eq a year or 22.5 GW nominal of coal after three years. But the EIA forecast was dated 2013 and it’s pretty clearly wrong. Actual production and therefore consumption has been completely flat from 2013 to 2017, and down 3% from the peak pre-crisis year of 2007, a ten-year run. Best just to note the truism that if electricity demand picks up - and there are no Trump policies to achieve this unlikely goal - it will slow the fall in production from coal plants, which are now the swing supplier. /update]

****************************

Notes to the table

The capacity plans and current coal installation are from a FERC staff paper, in turn citing Velocity Suite, ABB Inc. and The C Three Group LLC. The 2017 capacity factors are taken from the EIA table for 2017 (here, table 6.7A). For gas, I took an average of the different types weighted by total installed capacity (idem, table 6.1); big combined-cycle gas turbines have high ones, simple straight-through turbines installed as cheap peakers very low ones. For all the others, I frankly took a guess at the average, as it doesn’t make much difference. The outlier here is nuclear, which has a very high CF, but its net capacity is not expected to change significantly.

From the capacity factors I calculated the equivalent continuous capacity, as for an imaginary plant running 100% of the time. This is logically equivalent to comparing the expected annual energy production in Gwh. I just find the capacity metric easier to visualize.

FERC only sees utility-scale generating plants, so it leaves out entirely residential solar installed behind the meter, and much commercial solar. These together are currently running at about 5 GW a year, on a rising trend (in spite of a bad 2018). Say 1 GW continuous equivalent.

Well, in addition to saving our lovely little planet, I hope this may be the one time we actually do something about structural shifts in employment. Well since the Depression anyhow. I’m not thinking the odds of us getting our act together are that high, but, I could be wrong.

If, as most people expect, there’s a recession between now and 2020, electricity demand might even fall.