My friend Jesse Singal has a nice piece over at the Science of Us about Michael Javen Fortner’s new book, Black Silent Majority: The Rockefeller Drug Laws and the Politics of Punishment. “Key to this story,” Jesse notes, “is the role of Harlem’s residents in forcefully advocating for a tougher, more punitive approach to the neighborhood’s ‘pushers’ and addicts.”

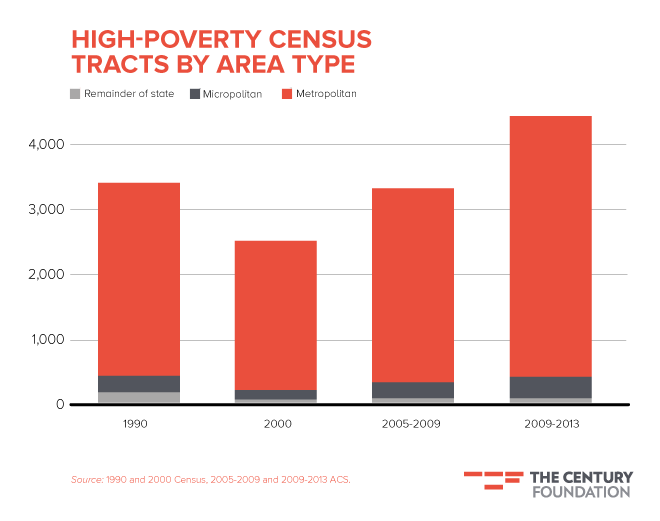

You should read Jesse’s piece, which includes some striking graphics.

There is a sad parallel to be drawn between criminal justice policy of the late 1960s and early 1970s and the respectability politics that blossomed fifteen years later around HIV and AIDS. David Dinkins, Benjamin Ward, Charles Rangel, and much of New York’s African-American political establishment opposed syringe exchange and other harm reduction policies ironically promoted by that noted liberal Ed Koch. That’s the world I entered early in my career when I researched these same public health issues.

This 1988 New York Times story, “Needle exchange angers many minorities,”captures one strain of the dispute:

More specifically, the needle exchange has been vehemently denounced by black and Hispanic city officials.

They, joined by many drug treatment specialists, contend that because the majority of the city’s addicts are black or Hispanic people, the needle program is misguided and insensitive. What is needed, many of them say, is more drug-prevention education and treatment centers in minority neighborhoods. So intense are the sentiments that City Councilman Hilton B. Clark of Harlem recently accused the New York City Health Commissioner, Dr. Stephen C. Joseph, of using the free needle program to conduct a genocidal campaign against black and Hispanic people.

Mr. Clark said that the needles, even if distributed for a limited period of six to nine months, will encourage drug use rather than contain AIDS.

Even the city’s Police Commissioner, Benjamin Ward, last week joined the debate. Some drug treatment experts suggest that debate illustrates more about the failure of the city’s black and Hispanic leadership to effectively combat AIDS in their communities than about the alleged insensitivity of City Hall to minorities.[…]

On a television call-in program Mr. Ward, who is black, called the exchange a ”bad idea” and said he opposed it as a law-enforcement official and as a black man.

”As a black person we have a particular sensitivity to doctors conducting experiments, and they too frequently seem to be conducted against blacks,” he said.

In a letter to Mayor Koch dated Oct. 27, the City Council’s Black and Hispanic Caucus said, ”It is beyond all human reason and common sense for the city to hand out needles to drug addicts at a time when our police officers and citizens have become casualties in the drug war.”

The current generation of African-American elected politicians is at the forefront of HIV prevention and treatment advocacy. In retrospect, Ward his allies were disastrously wrong. I wish we could go back and replay the initial poisonous reaction to essential public health interventions. But before we harshly condemn Ward and his colleagues ,we might consider the human consequences of the heroin epidemic in Harlem and similar communities, and consider our broader societal failure to address the widespread joblessness, addiction, and crime that beset minority communities long before AIDS came along.

Jesse concludes his piece with a simple point:

Lurking underneath Fortner’s intricate, careful parsing of the historical record, then, is a simple claim about human beings: If you live in a neighborhood where you feel like you, your family, and your possessions are perpetually at risk, it will harden your politics and your view of your neighbors. Fortner’s main goal is to remind readers that this isn’t just true of white people.

Indeed.