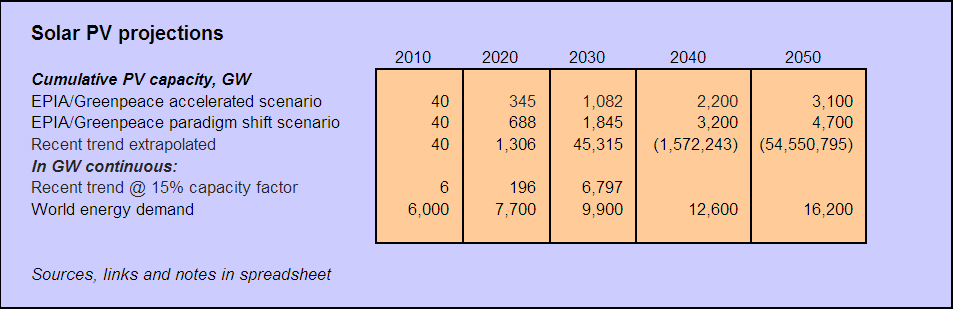

In January 2013 I published a long post on PV solar energy, under the grandiloquent title “Terawatt solar or bust”. For an inherently ephemeral blog post, it holds up pretty well. The heart of it was this table:

At the end of 2019, installed PV was 633 GW (Bloomberg NEF, via Wikipedia; may include a rough estimate of rooftop), with a central forecast of 770 GW for end 2020.

At the end of 2019, installed PV was 633 GW (Bloomberg NEF, via Wikipedia; may include a rough estimate of rooftop), with a central forecast of 770 GW for end 2020.

Half a terawatt is there already, and the second half can be expected for 2022. Yeah!

The EPIA/Greenpeace best scenario of 688 GW for 2020 was spot on. Remember that it was an outlier at the time, derided by the CW. The longhaired agitators at Greenpeace have turned out much better forecasters than the men in grey suits at the IEA.

My gloat is tempered by the fact that I tagged Greenpeace as too conservative, based on an extrapolation of past trends. I was wrong, and the growth rate did slow. I didn’t allow for the premature rush by many governments, from the UK to China, to phase out “unaffordable” solar subsidies too quickly. That exogenous shock has gone now, and there is little reason why solar should not get back on its previous fast track. Judging by their investment plans, Chinese PV manufacturers at least are betting on rapid growth.

What of the future? My dumb extrapolation had solar meeting the world’s entire energy demand of ca. 10 TW continuous soon after 2030. That implies 40 TW of solar at a 25% capacity factor. Say half would be wind instead, that’s still 20 TW of solar. A long way to go, but exponential growth is still the 500-lb gorilla that crushes everything in its path.

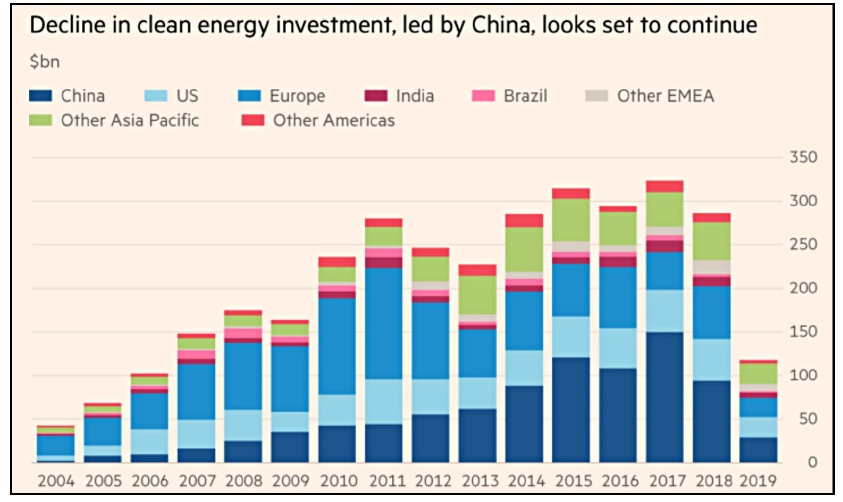

At current utility prices close to $1 per installed watt (*) (modules are at 20c per watt), the cost would be about $20 trn, or $1.3 trn a year for 15 years. Global investment in all forms of energy was $1.85 trn in 2018 (IEA), of which $726 bn was for oil and gas, so the order of magnitude is as doable as it is necessary. Note that the increase is only in the upfront investment. It is now a truism (pointed out here by me in 2015) that the energy transition at worst breaks even over time, because the running costs of renewables are so low. It’s a huge bargain if you add in health and climate benefits.

(*) The NREL gives the average US cost in 2018 as $1.60/watt, with $1 at the bottom of the range, which will soon become the norm. OK. Round up to $2trn a year at worst if you insist.

I did get a few things right seven years ago:

- There has been no dramatic change in solar technology, just steady incremental improvements.

- A lot more attention is being paid to the future problem of firming large volumes of intermittent solar and wind without carbon emissions. (The immediate problem is being successfully managed by grid operators everywhere using gas turbines.)

I’d just like to highlight a couple of recent developments before we go.

One is Andrew Blakers’ 100% renewables scenario for Australia using current technology and costs . He showed it can be done, at less than current wholesale prices, using just four technologies: wind, solar, HVDC transmission, and off-river pumped hydro storage. The beauty of this minimalist approach is that you can add in riskier technologies – V2G, P2G, large-scale demand response, grid batteries - if they (a) work (b) make things cheaper. But the feasibility problem has been solved. Blakers followed up by answering the “no sites” objection to PUHS by creating a world atlas of potential sites, identified from satellite data. There are 616,000 of them. Bad luck for Estonia and the Netherlands, but most countries have plenty of options.

I suppose the big technology news in renewables in the last few years has been the sudden arrival of floating wind. The Norwegian oil company Equinor went from one test turbine to an operational wind farm without a hitch, and now other players are piling in. This opens up large areas of ocean off coasts with no continental shelf, especially the US West Coast and the Japanese Pacific one.

For entertainment value though, it’s hard to beat the even more rapid arrival of agrivoltaics. This is a Sybil Fawlty invention (“special subject – the bleeding obvious”) but welcome for all that. It turns out you can actually improve yields of some crops by growing them in partial shade under solar panels. Here’s a nice shot of a project in a vineyard in the Languedoc.

The French get their priorities right. The AI management software that steers the panels gives priority to protecting the vines from extreme weather, such as hail – a serious risk to high-quality vineyards in Burgundy and the Médoc. The setup even improves the wine, perhaps by cutting heat stress:

The French get their priorities right. The AI management software that steers the panels gives priority to protecting the vines from extreme weather, such as hail – a serious risk to high-quality vineyards in Burgundy and the Médoc. The setup even improves the wine, perhaps by cutting heat stress:

It has also been claimed the aromatic profile of the grape was improved in the agrivoltaic set-up, with 13% more anthocyanins – red pigments – and 9-14% more acidity.

A toast to solar energy: take over the world as fast as you can.

One last post to come.

planted by Colbert to replace those he cut to build warships for Louis XIV – trees that have preservation orders on them. Even in a good cause, felling a thousand of them is not on.

planted by Colbert to replace those he cut to build warships for Louis XIV – trees that have preservation orders on them. Even in a good cause, felling a thousand of them is not on.