An exploited girl and a goddess-queen.

My reaction to Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring in the Mauritshuis museum in The Hague surprised me. I was expecting to admire this famous work by a great master, the favourite painting of the Dutch. It is indeed technically marvellous. Vermeer was one of the greatest technicians of oil painting ever. My problem with the picture is as a portrait. It’s formally a tronje, a painting of an unidentified and representative human figure. But it’s plainly not a stylised ideal but a portrait of a real girl. She has no name, perhaps (as in the film) a servant paid a few ducats to sit. I find it unflattering, and not by any lack of skill. Newspapers rightly get criticised for printing photos of politicians with their mouths open: everybody looks stupid when caught like this. Vermeer went to enormous trouble, over multiple sittings, to make his subject look dimwitted. She was exophthalmic anyway, and he faithfully reproduced or exaggerated this. The combined effect is disrespectful and exploitative. And to what purpose? Possibly to make a trite contrast with the perfection of the enormous pearl earring lent her for the occasion. Pshaw.

My reaction to Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring in the Mauritshuis museum in The Hague surprised me. I was expecting to admire this famous work by a great master, the favourite painting of the Dutch. It is indeed technically marvellous. Vermeer was one of the greatest technicians of oil painting ever. My problem with the picture is as a portrait. It’s formally a tronje, a painting of an unidentified and representative human figure. But it’s plainly not a stylised ideal but a portrait of a real girl. She has no name, perhaps (as in the film) a servant paid a few ducats to sit. I find it unflattering, and not by any lack of skill. Newspapers rightly get criticised for printing photos of politicians with their mouths open: everybody looks stupid when caught like this. Vermeer went to enormous trouble, over multiple sittings, to make his subject look dimwitted. She was exophthalmic anyway, and he faithfully reproduced or exaggerated this. The combined effect is disrespectful and exploitative. And to what purpose? Possibly to make a trite contrast with the perfection of the enormous pearl earring lent her for the occasion. Pshaw.

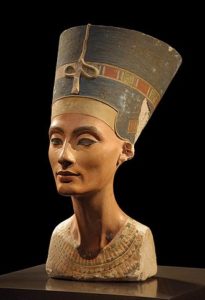

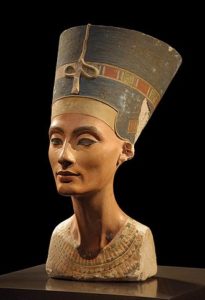

My second portrait is an extreme contrast: Nefertiti, Queen of Egypt for almost 20 years, in Berlin. Again, the extraordinary technical skill of the bust (about two-thirds life size) is indisputable. The effect is remarkable. She is not just beautiful but glamorous: beauty weaponized. (The origins of the word lie in Scottish witchcraft.) For what purpose? The classic glamour photos of Hollywood studio stars were designed to transform their exploited and vulnerable subjects into unattainable objects of sexual desire, in order to sell film tickets. Nefertiti didn’t need that; she was a Pharaoh’s queen already.

My second portrait is an extreme contrast: Nefertiti, Queen of Egypt for almost 20 years, in Berlin. Again, the extraordinary technical skill of the bust (about two-thirds life size) is indisputable. The effect is remarkable. She is not just beautiful but glamorous: beauty weaponized. (The origins of the word lie in Scottish witchcraft.) For what purpose? The classic glamour photos of Hollywood studio stars were designed to transform their exploited and vulnerable subjects into unattainable objects of sexual desire, in order to sell film tickets. Nefertiti didn’t need that; she was a Pharaoh’s queen already.

The Hollywood stars were metaphorical sex goddesses. Nefertiti was the real thing.

First, the sex part. There is no reason to doubt her depicted beauty. Her husband Amenhotep was portrayed as ugly, with distended belly and elongated limbs, possibly as a result of a congenital condition. So the burden of regal show, and quite likely of day-to-day rule, fell disproportionately on the queen. She rose to the challenge; she even had herself sculpted naked, a radical step in any culture that you can only get away with if you have a great body and total self-confidence.

Second, the goddess. Pharaohs and their consorts were semi-divine personages anyway, on speaking terms with the gods. But Amenhotep IV – Akhenaten – was determined on a religious revolution. He swept away the pantheon, and replaced it by a proto-monotheistic cult of Aten, represented only as the solar disc. The worship of Aten was carried out in courtyard temples open to the sky, not dark labyrinths. The Pharaoh and queen became the unique intermediaries between the people and Aten, and the priests were out of a job. They did not appreciate this, and after Akhenaten’s death staged a successful counter-revolution. His son Tutankhamun (by another wife) was buried surrounded by images of the old pantheon. The Aten cult was forgotten, the new capital at Amarna abandoned. While it lasted Queen Nefertiti was a sacred priest-empress, as near to a goddess as monotheism allows.

Second, the goddess. Pharaohs and their consorts were semi-divine personages anyway, on speaking terms with the gods. But Amenhotep IV – Akhenaten – was determined on a religious revolution. He swept away the pantheon, and replaced it by a proto-monotheistic cult of Aten, represented only as the solar disc. The worship of Aten was carried out in courtyard temples open to the sky, not dark labyrinths. The Pharaoh and queen became the unique intermediaries between the people and Aten, and the priests were out of a job. They did not appreciate this, and after Akhenaten’s death staged a successful counter-revolution. His son Tutankhamun (by another wife) was buried surrounded by images of the old pantheon. The Aten cult was forgotten, the new capital at Amarna abandoned. While it lasted Queen Nefertiti was a sacred priest-empress, as near to a goddess as monotheism allows.

Did the cult die? Sigmund Freud for one thought not. He suggested that the Aten religion influenced Jewish monotheism. Archaeologists pooh-pooh this. The Egyptian captivity is generally considered unhistorical; all the evidence points to a Canaanite origin for Judaism. But in that case, where did the story of the Exodus come from? Canaan was often a frontier province of the Egyptian empire. Metropolitan political and cultural upheavals would have filtered there during Akhenaten’s quite long reign (ca. 1350 BCE) . A contribution to early Jewish developments is certainly possible – it’s more believable than the bloodthirsty fantasies of the unread Book of Joshua. Once you ask “Why not one?” the question is hard to put away.

Maybe Nefertiti is still our Queen.

* * * * *

PS: If you enjoyed my offbeat art history, you might take a look at some older posts on women subjects and great artists: Bernini, Botticelli, Ghirlandaio, Michelangelo.

My reaction to Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring in the Mauritshuis museum in The Hague surprised me. I was expecting to admire this famous work by a great master, the favourite painting of the Dutch. It is indeed technically marvellous. Vermeer was one of the greatest technicians of oil painting ever. My problem with the picture is as a portrait. It’s formally a tronje, a painting of an unidentified and representative human figure. But it’s plainly not a stylised ideal but a portrait of a real girl. She has no name, perhaps (as in the film) a servant paid a few ducats to sit. I find it unflattering, and not by any lack of skill. Newspapers rightly get criticised for printing photos of politicians with their mouths open: everybody looks stupid when caught like this. Vermeer went to enormous trouble, over multiple sittings, to make his subject look dimwitted. She was exophthalmic anyway, and he faithfully reproduced or exaggerated this. The combined effect is disrespectful and exploitative. And to what purpose? Possibly to make a trite contrast with the perfection of the enormous pearl earring lent her for the occasion. Pshaw.

My reaction to Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring in the Mauritshuis museum in The Hague surprised me. I was expecting to admire this famous work by a great master, the favourite painting of the Dutch. It is indeed technically marvellous. Vermeer was one of the greatest technicians of oil painting ever. My problem with the picture is as a portrait. It’s formally a tronje, a painting of an unidentified and representative human figure. But it’s plainly not a stylised ideal but a portrait of a real girl. She has no name, perhaps (as in the film) a servant paid a few ducats to sit. I find it unflattering, and not by any lack of skill. Newspapers rightly get criticised for printing photos of politicians with their mouths open: everybody looks stupid when caught like this. Vermeer went to enormous trouble, over multiple sittings, to make his subject look dimwitted. She was exophthalmic anyway, and he faithfully reproduced or exaggerated this. The combined effect is disrespectful and exploitative. And to what purpose? Possibly to make a trite contrast with the perfection of the enormous pearl earring lent her for the occasion. Pshaw. My second portrait is an extreme contrast: Nefertiti, Queen of Egypt for almost 20 years, in Berlin. Again, the extraordinary technical skill of the bust (about two-thirds life size) is indisputable. The effect is remarkable. She is not just beautiful but glamorous: beauty weaponized. (The origins of the word lie in Scottish

My second portrait is an extreme contrast: Nefertiti, Queen of Egypt for almost 20 years, in Berlin. Again, the extraordinary technical skill of the bust (about two-thirds life size) is indisputable. The effect is remarkable. She is not just beautiful but glamorous: beauty weaponized. (The origins of the word lie in Scottish  Second, the goddess. Pharaohs and their consorts were semi-divine personages anyway, on speaking terms with the gods. But Amenhotep IV –

Second, the goddess. Pharaohs and their consorts were semi-divine personages anyway, on speaking terms with the gods. But Amenhotep IV –