Keith has turned off comments so I’ll reply to his thoughts on recent UK vs US economic performance by return of post.

If you want to compare the policies since 2008, the relevant data cover the whole period since 2008, not the last quarter of 2013 and an estimate for 2014.

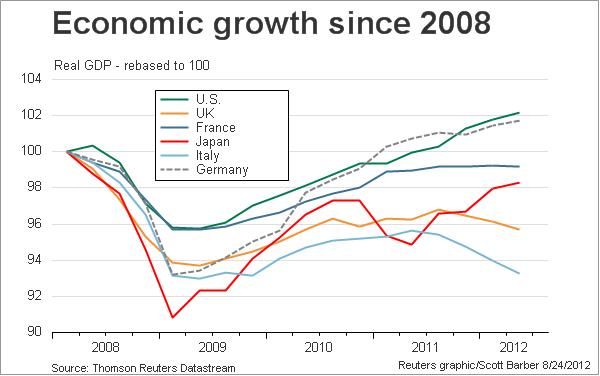

Here’s the key chart, courtesy of Thomson Reuters:

It’s not a matter of debate but of fact that the British economy has underperformed the US one over the period by a substantial margin. The relative loss came to 6% of annual GDP by 2012, cumulatively around 15% of a year’s GDP. This contrasts with a slight British overperfomance previously (see the chart since 1999 on the same page), so the gap is very unlikely to have a structural explanation.

The Keynesian argument was and is that this shortfall represents a simple throwing away of at least $300 billion of potential work and output. That’s a rock-bottom minimum, as the benchmark US policy has hardly been aggressively Keynesian; for that you have to go to Australia or recent Japan. What has Britain gained from this? The bond vigilantes have been kept at bay; but then they have not appeared in either the USA or Japan, so the policy looks like elephant powder. The welfare state and local government have been trimmed, which the cynical suspect to have been the main point all along.

The austerian argument (made in good faith or not) has been that austerity forces neoliberal structural reforms that raise the long-term growth rate. So far, it’s a claim with singularly little evidence for it, far short of what would be needed to justify the widespread suffering the policy has directly caused. Germany has done better than the other eurozone countries, and had mild structural reforms in 2010. But Italy and France have suffered, and the Nordics prospered, without reforms; Spain, Greece, Ireland and Portugal have been forced to put on the hair-shirt, and Britain’s Coalition government freely chose one, in both cases to little benefit. The hair-shirt was made more bearable to élites by the fact that it was always to be worn conveniently by the poor, never by the financiers who triggered the crisis or the policymakers and pundits who enabled it.

You can trust The Economist on facts. Interpretation, not so much.

You cannot hope to bribe or twist,

Thank God, the British journalist.

But seeing what the man will do

Unbribed, there’s no occasion to.

Update: I see Kevin Drum beat me to it. But only my post has Humbert Wolfe.

James

Thanks for this post. It irked me that such an incomplete and misleading post by Keith was posted without the possibility for comment. I understand that he opted for his own comment policy, but it might frustrate those looking for just the facts, that they not be able to rebut those given out of context.

Thanks for this post James. My post was alas, badly written to make the unsustainable claim that one can only evaluate economic policy years down the road. I started with something that surprised me (similar growth projections in 2014 and 2015) and I thought would interest people. I should have couched it in terms of asking how many people involved in economic debates in 2009-2011 would have guessed that rates would converge despite such different policies (I wouldn't have). Instead, I framed the post as if the 2014/2015 data were the final word, which they are clearly not. Kevin Drum, ever the gentleman, did though at least thank me by email for giving him something to write about this morning, which may have been the only social good I achieved with my not ready for prime time post.

Was it really a surprise to anybody that at some point the two growth rates would converge? The British economy suffered a steeper drop from trend, so it's natural that in any sort of recovery the bounce-back growth rate would be higher. You can also compare the two economies around 1935, where the situations were reversed.