Millions of Americans, particularly those with modest incomes or those who are just starting out, struggle with credit card debt. Although we all know high-interest debt is financially dangerous, much of this market remains rather mysterious. How do most of us actually use credit cards? How much we pay for the privilege? How do these patterns vary among people with different credit scores.

Over at Vox today, I had an interview with my gifted cross-campus Neale Mahoney. He’s one of the authors of my favorite financial economics paper published in 2015. It explores many of these concerns. This is one of the articles I’ve written to expand on (or explain the foundations of) our Index Card book released last week.

The paper, “Regulating consumer financial products: evidence from credit cards,†was written by Sumit Agarwal, Souphala Chomisengphet, Neale Mahoney, and Johannes Stroebel.  The study examined 2008–2012 data from a mammoth database of 160 million credit card accounts at America’s eight largest banks. The paper used these data to analyze the practical impact of the 2009 Credit Card Accountability Responsibility and Disclosure (CARD) Act, which Congress passed in 2009.

The authors found that the CARD Act was a triumph of financial regulation. Consumers paid almost $12 billion less in fees every year, with little sign of offsetting unintended effects. My Vox article shows why. That piece left many things on the cutting room floor, for reasons of space. Here are some additional fun charts. I generated these with the authors’ data. The complete interview with Mahoney (edited for space and clarity) is shown at the very bottom.

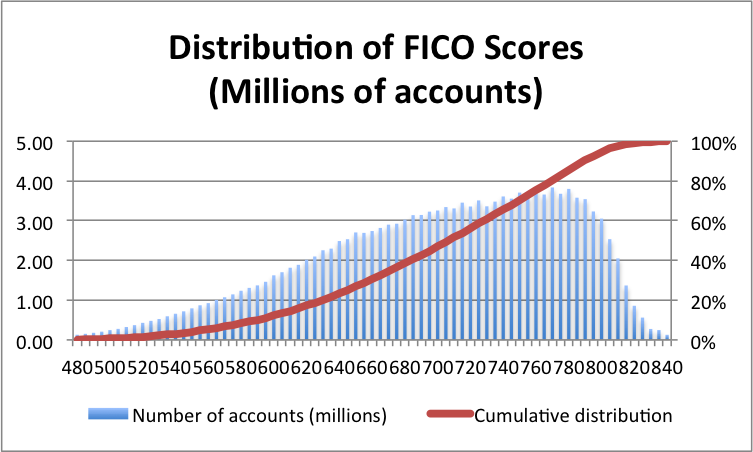

The first chart shows the distribution of FICO scores. The blue line is a histogram. The red is a cumulative distribution. For this period of the data, median scores are about 705, with a mean of about 700.

Now fasten your seatbelt for some more complicated stuff.

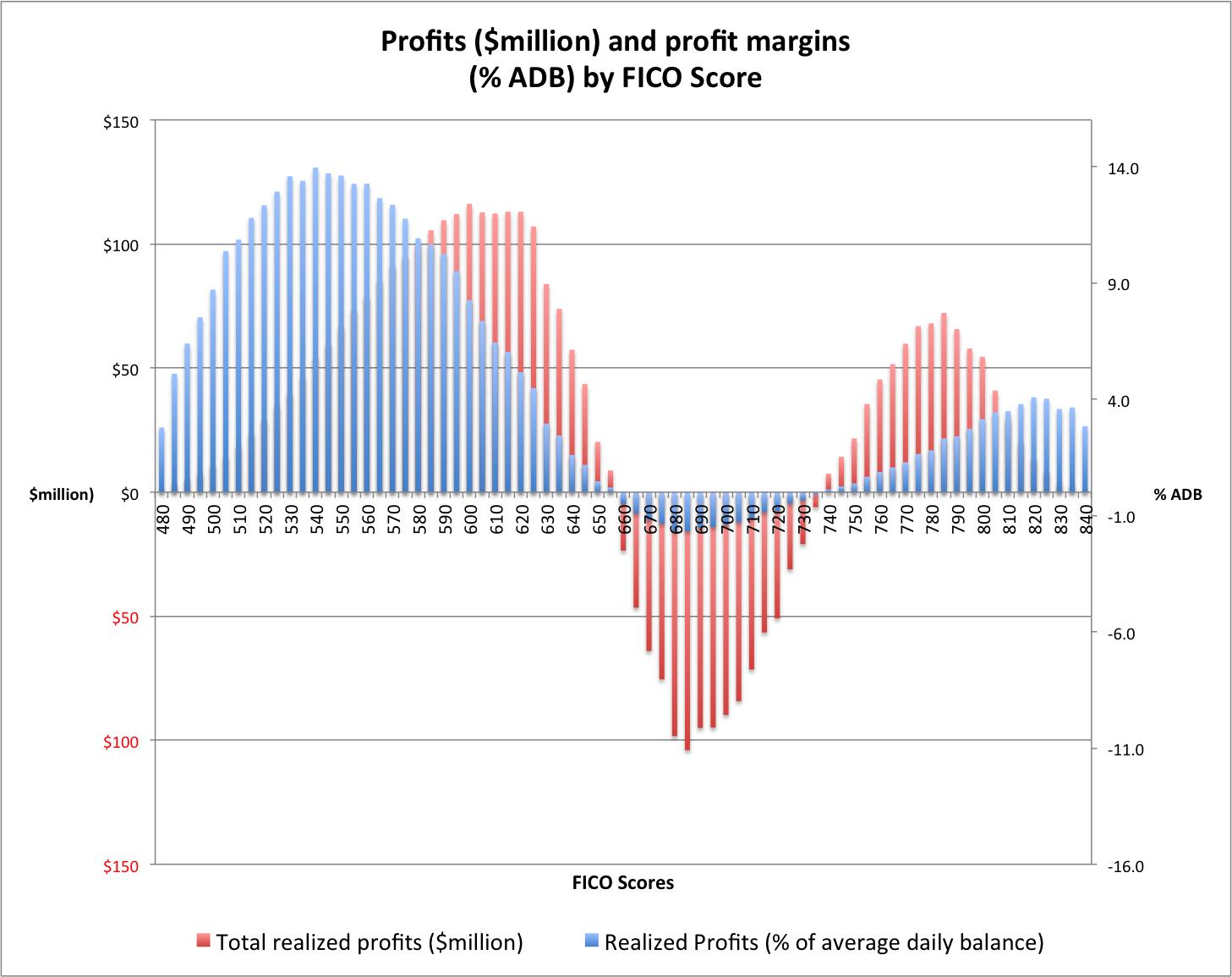

The next chart shows a histogram of credit card issuer profits at each point in the FICO distribution, shown in absolute dollars (the maroon bars) and as percentages of consumers’ average daily balances (the blue bars).

As you can see by the blue bars, profit margins are really high for the small group of borrowers with low FICO scores in the range of about 550. Amazingly, the industry made about $0 in cumulative profits on the top 80% of accounts that have FICO scores exceeding 630. The bottom 10% of accounts account for the majority of total industry profits. It’s also striking that the industry actually seems to lose money on consumers near the median of the distribution with FICO scores around 700, and then makes profit again on the best credit risks.

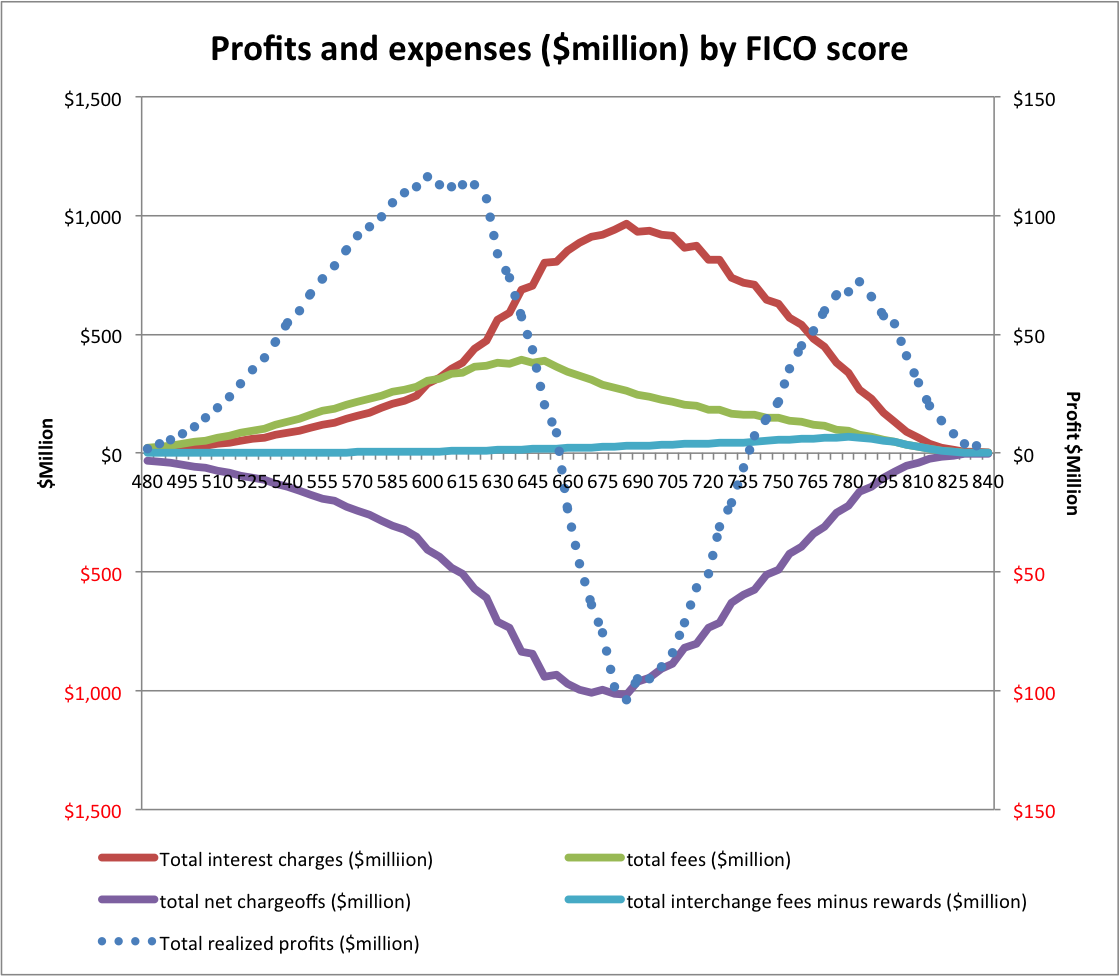

Below, profits and expenses are broken down in a different way. Net charge-offs are shown as negative, since this is bad debt.

What you can see in the (weird) graph is that consumers with FICO scores below 600 pay more in fees than in interest payments. Moreover bad debt for these consumers is surprisingly low in dollar terms—presumably because credit card issuers impose more stringent limitations. (Interchange fees from merchants are about 2% of purchases. They are pretty much offset by the costs incurred of credit card reward programs. Mahoney provided the net of these two in his spreadsheet to me.)

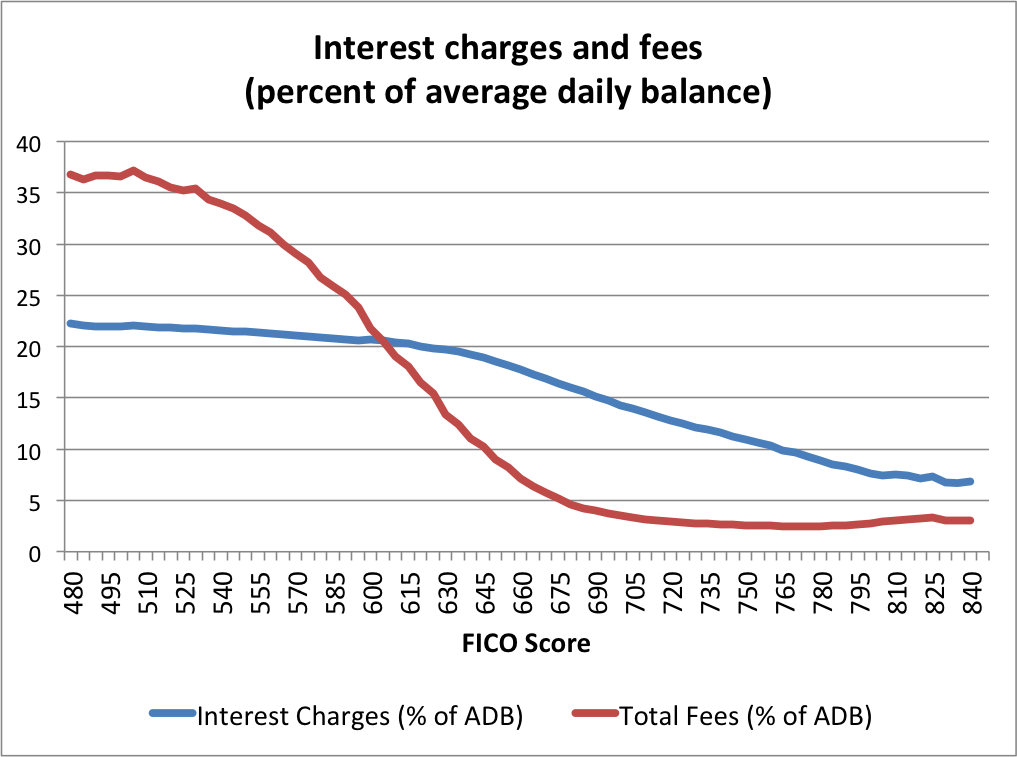

It’s striking that the burden of various fees falls so heavily on people with poor credit, and are a pretty minor nuisance for everyone else. Perhaps this disparate impact explains why this problem went unaddressed for so long. Fees exceed 30% of ADB for every FICO category below 560, compared to about 3% for accounts with FICO scores above 700—roughly the top half of the distribution.

Note added 1/10. Many readers asked how it could be that credit card companies could lose money on so many people near the meat of the distribution. I had all sorts of theories-all of which involved overthinking. Mahoney writes via email:Â

The explanation for the negative profits is very simple. The data are from 2008-2010, which was, of course, during the heart of the Great Recession. What we’d expect in a perfectly competitive market is for banks to make money during good times and lose money during bad times but to earn zero profits on average. What was striking to us is that even during a time when lenders “should” have been losing money, they were making positive profits throughout most of the FICO distribution, and earning particularly large amounts from borrowers with the lowest FICO scores.Â

The complete interview (edited for clarity and brevity) is shown below.

Pollack: Let’s start with the basics. Most of us have credit cards. What is the single piece of advice you would give to consumers trying to manage their credit cards properly?

Mahoney: Pay off all your credit cards in full every month. If you can’t pay off all your cards, pay as much as you can on the card with the highest interest rate, and make the minimum payments on the others.

Pollack:Â What percentage of consumers pay their entire bill every month? What percentage of consumers just make the minimum payment?

Mahoney: In our data, 30.1% of account holders pay off their bill in full. At the other extreme, 13.0% of borrowers only make the minimum payment, and 14.7% make payments of less than the minimum amount.

Pollack: Which customers are the most profitable for credit card companies? Which are the least profitable?

Mahoney: Credit card companies make the most money from consumers with the worse credit scores, mainly because these consumers pay a large amount in fees. Credit card companies also make sizable profits from consumers with the best credit scores, who generate a lot of “swipe fee†revenue. Consumers with average credit scores – who are better at avoiding fees, but don’t spend a large amount – are still profitable, but less so than high and low credit score consumers.

Pollack: The CARD Act forced credit card issuers to change some of their practices. Can you tell me some of the key consequences of that law?

Mahoney: The CARD Act did two main things. First, it restricted a number of credit card fees. Second, it required credit card issuers to provide information on annual statements that was designed to “nudge” consumers into making larger monthly payments on their cards. In our research, we estimate these laws saved consumers approximately  $12 billion per year, with the fee regulations accounting for nearly all of this effect. Just as important, we do find any evidence that card issuers offset the reduced fee revenue by increasing interest rates (or other fees not targeted by the law) or by reducing access to credit.

Pollack: Which of the CARD Act provisions seem most successful, and why? Why was this law more successful than (say) many regulations on payday loans?

Mahoney: Most of savings came from the elimination of over limit fees, which were a major source of revenue before the CARD Act. The regulation was successful because it targeted a hidden fee, which was not already disciplined by competitive pressures, and because credit card issuers could not easily offset the reduced fee revenue with, for example, higher interest rates or annual fees. Of course, even if the fee reductions were offset, making pricing more transparent would have been a desirable outcome.

Pollack:Â What policy issues concern you right now in regulating credit cards? Would you make any changes to law or regulations to improve the operation of the credit card sector?

Mahoney: I think there’s a real question as to whether teaser rate — or zero introductory APR — credit cards are good for consumers in general. Obviously some people manage to transfer their balances when the introductory rate period expires, and these cards are a good deal for these consumers. But the reason credit card issuers promote these products is that some people (either because of bad luck or bad planning) don’t transfer their balances and end up paying large amounts in interest, that they probably didn’t expect to pay. I’m not sure if we want a product that is based taking advantage of bad luck or bad planning to play such an important role in the market.

The most significant insight from this erudite analysis is actually in the background: credit scores (and reports and records) are all about credit industry profits. They are derived from limited types of information available to the score-setters, and ignore many other important factors. They are not, and were never designed to be, good faith metrics of consumer financial well-being. To the contrary, they are widely used by the credit industry as a crude bludgeon to push consumers into acting in the industry's interests rather than their own. "Don't even think about standing up for your rights or giving us any grief, or we will do bad credit rating at you." It works. My advice to any consumer making a financial decision is first to decide what you would do if there was no such thing as a credit rating, record or score. Then consider modifying a decision for credit record reasons only if there is a truly compelling reason. Whenever you think about your credit score, be aware that you are being manipulated. My views here are informed by a career as a lawyer specializing in consumer debt reorganization, bankruptcy and related matters.

Is the swipe fee the same thing as the interchange fee?

Yes. And I have a hard time understanding how it can be offset by credit card rewards when so many cards have no rewards at all, and few have rewards even approaching 2%.

Excellent charts. They exhibit perfectly one of Edward Tufte's principles: charts are best for visualising large volumes of data. Those pie charts giving three percentages are a waste of ink and don't add anything to a three-line table. Harold's second chart extracts a simple and convincing story from 74 data points, in a way impossible in a table.

Question: do Americans use debit cards at all? I don't have a credit card now, and have not done so for most of my adult life. An instant debit card is like a checkbook, it forces you to have at least a general awareness of your bank balance at all times. Borrowing money has to be an explicit decision, with quite high transaction costs. The disadvantage is that I probably don't have a credit rating at all.

Debit card usage is growing in the US with Visa and MasterCard alone having about 655 million cards in circulation.

A card in circulation is not the same thing as a card in use. Most banks issue debit cards in lieu of ATM cards unless you specifically ask for an ATM card. I carry a debit card at all times but use it in only three circumstances: (1) the gas station nearest my home gives 10 cents per gallon for using it (or cash) instead of credit, (2) the Costco gas station on the way to work accepts only debit cards, not credit cards, and (3) I am at the supermarket and would like some cash but don't feel like visiting the ATM (unlikely, as the ATM is just a few hundred yards from the supermarket), and I'm willing to give up my 2% credit card rewards and use my debit card in order to get cash back.

Ah. Recent EU legislation capped the swipe fees paid by merchants at 0.2% for debit and 0.3% for credit cards, leading card issuers to drop their (measly by American standards) perks.

The complaining banks have not quit offering cards, so the EU percentages must roughly cover the real costs of processing. American consumers are being ripped off on a colossal scale, at least 1% on every card purchase.

Debit Card Statistics

Debit cards are not uncommon in America, and as cartman mentions, most banks offer them as the default for ATM cards.

They were worse than credit cards at the low end of credit scores, since most bank's overdraft fees were as high as or higher than the overlimit fees on credit cards, and if your balance was low, holds could get you hit with an overdraft fee even if you always had money in the account. Also, bounced check fees are extremely high and mismanaging a debit card could result in a bounced check.

Is that profit line correct? Just eyeballing the values at 700, interest plus fees exceeds 1 billion and writeoffs are just under 1 billion. That should be a profit.

The two different scales are very confusing. I have to assume that the right scale applies only to the dotted blue line.

Or maybe not. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/volokh-conspi…