The European Union is flaking on climate change, because doing anything about it will hurt GDP in the short run. This is particularly nuts for them, because Europe is a lot further north than most people realize: the latitude of New York is also the latitude of Madrid and Rome; London is up there with lower Hudson’s Bay. Of course, global warming might just put the Scots and Swedes in the wine or even banana business big time. But it also might mess up the Gulf Stream that gives Paris a milder climate than New York rather than the climate of Fargo.

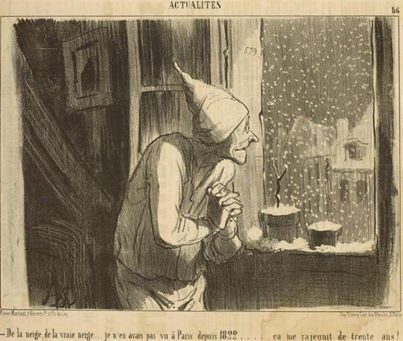

Snow,real snow…I hadn’t seen any in Paris since 1822…it makes me feel thirty years younger!

Snow,real snow…I hadn’t seen any in Paris since 1822…it makes me feel thirty years younger!

Not only will a lot of Europe around the edges be going under water, but a lot more will be Arctifying while the rest of the world broils. This pullback is not surprising, unfortunately. The hard truth about climate stabilization follows from the non-negotiable fact that the atmosphere is well-mixed, so a pound of CO2 released anywhere has about the same warming effect everywhere: the climate benefits of greenhouse gas (GHG) reduction are diluted all over the world. About a ninth of the people in the world live in Europe, so the European benefits of $1m worth of climate stabilization are only about $110,000: to be worth it for them, climate policy has to have a benefit/cost ratio of 9. That’s really hard to achieve, and the math is much more discouraging for any single country in the EU. Even worse, the payoff comes after pretty much everyone in office is retired or dead.

What we have here, friends, is the granddaddy of all prisoners’ dilemmas, implicit in Hedegaard’s remark “It will require a lot from Europe. If all other big economies followed our example, the world would be a better place.†Even for countries as big as China or maybe India, and even there for policies with a nice fat B/C ratio like, say, 6, the smart move if you think the rest of the world will step up and act is to do nothing and coast on it, and if you think the rest of the world won’t, to do nothing and at least not be a chump. The collapse of European will results from tacit understanding of this game structure.

Human institutions have never dealt with a situation like this at this scale. Little wonder that we are invoking magical thinking (“we’ll all get rich making windmills!”. Climate stabilization is really expensive now. It’s worth it, but not soon and not for any jurisdiction acting by itself. At times like this, only the bitterness of Ambrose Bierce suffices:

A BEAR, a Fox, and an Opossum were attacked by an inundation. “Death loves a coward,” said the Bear, and went forward to fight the flood. “What a fool!” said the Fox. “I know a trick worth two of that.” And he slipped into a hollow stump. “There are malevolent forces,” said the Opossum, “which the wise will neither confront nor avoid. The thing is to know the nature of your antagonist.” So saying the Opossum lay down and pretended to be dead.

[edited for clarity 24/I/14]

Can you say “carbon import tariff”? That’s how you solve the free rider problem for your own solutions, and become incentivized to come up with your own solutions lest someone impose a carbon import tariff on your exports.

That’s why the Obama Administration fight against airline carbon tariffs in the EU was stupid to the Xth power. The EU didn’t help though by bogarting the revenues instead of sharing them.

You had to get halfway down the story before reaching this gem:

“Germany’s plans to shift away from nuclear power by 2022 and to encourage the development of alternative sources are running into complications including higher energy costs for industry and consumers.”

IOW, the problem is not lowering CO2. The problem is lowering CO2 while abandoning the most reliable source of CO2 free baseline power.

IOW, the problem was not inevitable, but was a consequence of the global warming activists being nuts on the subject of nuclear energy, to the point where they won’t admit it’s a CO2 reduction if it involves splitting atoms.

Or maybe nuts, period, because they’d apparently rather Europe burn lignite than natural gas, despite the comparative CO2 profiles.

What is on display here, simply put, is the consequences of setting a goal, and then rejecting the most economical way to achieve it.

I’m afraid that the situation is not quite that simple, Brett (leaving aside the fact that there are plenty of European countries other than Germany).

But briefly put, Germany has a waste disposal problem. This includes not only conventional waste (and is a reason why Germany is so aggressive about recycling and wants to phase out landfills in the near future), but also extends to nuclear waste; in fact, it’s probably much worse for nuclear waste.

Germany is lacking in deep geological repositories suitable for holding nuclear waste permanently. Two repositories that were previously assumed to be safe turned out to be not so safe, but are now in danger of collapsing (Schacht Asse II and Morsleben). Not only does Germany have to figure out where to store new nuclear waste permanently, but also what to do with the existing waste from the parts of Morsleben that may be collapsing. Morsleben currently holds over 40k cubic meters of radioactive waste, and the cost for its closure is estimated at over 2 billion euros.

Needless to say, without having a plan for what to do with nuclear waste, further investment in nuclear energy may not be the smartest thing to do.

These concerns could at least be partially alleviated with a fuel cycle that recycles most nuclear waste, but that is currently either pie-in-the-sky technology, very expensive (and thus wouldn’t solve the economic issues), or both. Not to mention the nuclear proliferation concerns that would come with it.

On top of that, existing nuclear reactors in Germany have been plagued by repeated incidents, which have also driven up the actual cost of nuclear power in Germany.

Would it help Germany if they weren’t shutting down their nuclear plants? Not as much as you’d think (even assuming they could deal with the remaining problems). Electricity makes up a little over 20% of final energy consumption in Germany, a little over a 20% of which used to be produced by nuclear plants. This is not to say that working nuclear power wouldn’t help, but the far bigger problem is how to generate the remaining 80% of energy needed that isn’t electricity.

These comments, focusing on a real issue and not mentioning US electoral politics or such, illustrate (a) why I think this is the best blog I read, and (b) why I hate the idea of eliminating comments.

OTOH, I also understand Keith Humphreys’ point about having to waste time and energy being the baby sitter. I don’t think there’s any good reason for ad hominem attacks on other participants, nor for generally foul behavior.

I think a rational approach might be to institute a “three strikes” rule-violate the protocol of good manners three times and the umpire simply boots you out of the game. So the blogsters would not totally eliminate their baby sitter role, but they wouldn’t have to deal with the same misbehaving children over and over again. And my guess is that there aren’t terribly many of those miscreants; I think most of us are pretty well behaved.

There’s no other solution besides careful, consistent moderation. That’s the difference between comment rooms like this one, Making Light, and Crooked Timber on the one hand, and, say, Kevin Drum on the other.

Whatever rule you come up with, be it “three strikes” or something else, it still requires a thoughtful and engaged human to execute it. It takes time, and if you’ve got more important ways to spend your time than aggressively and consistently weeding your online garden, turning off comments is a sensible solution.

Concur. The landlord could shut off my comments without affecting much, but shutting off Katja’s would greatly diminish the RBC.

Nuclear waste has never been much of a problem except in people’s minds. You could take all the nuclear waste from all the nuclear power plants that have even been, stack them on a soccer field or a building, and put a barbed-wire fence around them with a sign - Danger! Radioactivity. The quantity is not large. Probably a little more precaution (against terrorists, say) wouldn’t be a bad thing, but the idea that this is a major show-stopper is silly. Note that several European countries are replacing their nuclear with coal power. Coal releases CO2, the waste tends to be more radioactive than most nuclear waste, and there’re millions of tons of it.

People get fixated on stuff and it leads to bad decisions.

I can simplify the nuclear issue:

Existing nuclear = good

Shutting down existing nuclear = bad

Expanding nuclear = bad

That’s the economics in a nutshell, just not that difficult.

Aside from the problem of where you put the waste, the main issue with nuclear is basically the same as it is with petroleum: externalities. It’s different in that the externalities from oil are incremental, constant, global, and hard to notice, while those from nuclear are spectacular, rare, and more (though not greatly) localized but that’s still what’s going on.

After Chernobyl the nuclear boosters assured everyone that it was a one off and that we wouldn’t see accidents like that again because other reactors used different technology that wouldn’t lead to catastrophe. Since Fukushima they’ve been saying the exact same things again. How many mulligans do they get?

Your analysis is even more compelling for California, a smaller economy than Europe and doing very expensive things. It’s hard for me to visualize India and China foregoing cheap energy if USA and Europe leave it on the table, so it has seemed to me that the only plausible path was for USA and Europe to do as much research as we can on cheapening renewable sources, getting their costs down, and making the results available free. All of the $3-per-barrel Saudi oil will get pumped and burned by somebody, as will the cheap-to-mine Australian coal, but if we can lower the cost of alternatives, maybe Brazilian and Mexican deep sea wells won’t be worth it, nor complicated Polish fracked gas.

So I’m with Brett here, and also eager to see work on biodiesel from cornstalks.

Repetition isn’t a bad thing, so I’ll try again:

Carbon tariff.

Carbon tariff does damn all on commerce between China and Philippines, nor on internal China commerce. Somewhat helpful in forcing emissions down on China factories which sell to us and to Europe, though it’s going to involve US Customs guys inspecting hundreds or thousands of China factories which have every incentive to appear less emissive than they are. I’m still going to bet that every barrel which costs $3 to lift will come out of the ground. You going to remit on stuff going out of the US? Or will all of our foreign markets get ceded to China? Just asking.

I could imagine a remit for exports to countries that don’t impose their own carbon tariff on third party non-compliant imports, but that’s unnecessarily complicated. A carbon tariff will make up for the majority of the economic problem and will incentivize noncompliant countries to clean up their act.

As for trade between China and Philippines, that doesn’t cause a trade imbalance for the EU.

I’m okay with the cheapest oil coming out of the ground. We need to get to zero net carbon pollution by 2050, that’s plenty of time to use up the cheapest stuff, and read Wimberly here at SF about how the cost of renewables are dropping dramatically in the meantime.

Maybe I am missing something, but I see no incentive here for China and India to lessen their emissions. It simply cedes the rest-of-world market for manufactured goods to BRIC and raises USA/EU energy costs in the short term.

We are all in this together, and BRIC incentives are, as Mike pointed out, to keep on keeping on. The results, for us, of emissions anywhere are roughly the same, long term. Wimberley’s reports on lowering costs are the most hopeful think out there; if these trends continue we and the rest of the world will benefit.

sorry, anonymous was me.

It’s too bad we don’t have any international forums where countries could negotiate with one another to address problems like this, or even mechanisms whereby one set of countries could offer incentives to another set of countries to do thing that helped the first set (and the rest of the world.)

Meanwhile, I am always pretty astounded at the blithe use of cost-benefit calculation in situations like this, where the potential avoided costs are pretty close to unbounded. If you’re going to argue that no, you shouldn’t spend the money because actions by other might negate your efforts, then you should really be investing in Plan B — which for Europe would be making plans to move most of the population and finding another continent to move them to.

I don’t see this in the same light at all. I think Brad Plumer’s article in Wonkblog or Rob Stavins blog piece are much more on the mark. its just not clear that a county specific renewables policy gets you much once you already have cap and trade. There are some real pieces of good news about the cap and trade system. The EU set a more aggressive 40% cut by 2030 and they have put in a reserve pool of allowances like California has to keep prices in a predictable range. In other words, they are slowly altering their cap n trade to make it more tax like.

I see more good than bad news. Making the EU ETS a better, more stringent program is goal number one.

A weakening of the Gulf Stream would indeed cool down the continent of Europe, but it won’t give Paris the climate of Fargo. The Dakotas are way inland, while France is near or on the coast. If you want some sense of what no-Gulf-Stream could do to the climate of Europe, don’t look at the middle of continents. Don’t look at the northeast of continents either, because the North American northeast is cooler than it might be because it’s exporting heat to Europe. Look instead at the northwest of the North American continent, which doesn’t benefit from a gulf stream but isn’t handicapped by one either. There you’ll see that agriculture is possible half way up Alberta (it is really cold there but the province actually has two million-plus metro areas). On the coast, people live in numbers all the way up to Anchorage, Alaska, which is mellower than you might think. If British Columbia weren’t a solid mass of mountains, it would be more densely settled than Alberta. Looking back to Europe, you’ll see that while Scandinavia might be in some difficulty, the real losers would be the Russians. They already live places that are obnoxiously cold, and no-gulf-stream would be a real killer for them. You could see recent Russian population losses returning with a vengance.

Some green activists are characterising the EU Commission’s proposals as a punt, but I don’t see it. The centrepiece is a firm target of 40% emissions reductions from the 1990 baseline by 2030 (page 5, first paragraph, and page 18). It fudges the secondary renewables target of 27% a bit by making it an an EU average (same paragraph), giving member states like Britain the option to waste money on the nuclear sideshow if they want. The flexibility is not a cop-out, rather a licence for the Commission to interfere continuously in national energy policies, as it likes. Page 12, my italics:

The Commission makes proposals to revive and tighten the ETS cap-and-trade system, including an increase in the annual rate of reduction in the cap to 2.2% after 2020 (page 5). I’m not competent to assess whether they will be enough. If there is a risk of real backsliding, this is where it will happen. But the European Parliament reversed its vote against tightening the allocations.

The 40% target is not conditional on action by the US, China and India (page 6), but an attempt to lead by example. If they did follow, the world would just about be on track for climate stabilisation. Mike is therefore wrong in my view to see the issue as a worldwide political logjam. It’s down to these three countries.

Interestingly, the Commission thinks (page 5) that current policies would lead to a 32% reduction, so the additional effort is only 8%. Surely doable.

A legislature cannot bind itself, so I’m not sure what “firm” means; the technical term for software to be delivered a year from now is “vaporware”. Moving a target down while the date moves out is not the same as doing something now that hurts. Also, because the new rules don’t say they are conditional on the actions of others doesn’t mean they aren’t, especially as the costs of compliance start to bite.

The target decline has increased. The first iterations were like a 35% cut and they have gone to 40% with the cap declining yearly at a faster rate. That is firm legislation. Of course anything can be repealed, but they are going forward on this not back. And as far as I know there wasn’t an earlier target date, its was always 20% by 2020, which they will hit, and then more targets in 2030 and 2040, which were not firm, but now are.

I hope you’re right and I’m wrong (about how things will unfold in the future).

So, does anyone know who has a good website with information about comparative costs in the US for renewable power and solar panels and what-not? I’m looking for something that is not too advanced for people who aren’t total quants, but is also objective and trustworthy. As in for example, what is the math on buying a Prius these days?

Off the charts. A Prius is just as luxurious as any other $25,000 car and is one of the most reliable vehicles ever made. Mega resale value and top marks in Consumer Reports scores of owner satisfaction. Add on top gas mileage and it’s a complete winner.

Ah, well yes. I can only dream. It would be just lovely even to have something that didn’t emit bad things. Not to mention those dandy little rearview cameras.

Anyhoo, I was asking for a friend, who said that she had read that solar panels — if you added up all the emissions to make them, etc etc — weren’t really green yet. I have a feeling that’s not necessarily true, esp once you start adding in the different values of energy according to time of day, blah blah blah — but, you know, I haven’t done that math myself and I have other stuff to do. So I was hoping someone else already did it. With maybe less granular detail than, say, one of James’ posts, which usually lose me a little. (Of course, a lot of times, it matters how much value you assign to, say, clean air in the first place. I think though she just meant the economics didn’t work. She wasn’t saying it wasn’t worthwhile for other reasons. I can snoop myself, but lots of smart people hang out here so I was being lazy. Or, conserving energy? ; >)

I wish there were some reasonably simple, solid truths about this stuff. One is that conservation is always green. You can’t go wrong if you use less stuff, burn less fuel (Prius, but a plug-in hybrid is even better even if your electricity comes from coal), turn the heat down and wear a sweater, and eat less meat.

The capital required to make non-fossil energy (steel and concrete for nuclear and wind, other stuff for solar collectors), is not trivial, and analyzing carbon footprints requires making assumptions about, for example, how long a windmill will keep operating. There’s no substitute for getting the data, doing the analysis carefully, and being prepared to count stuff we didn’t think about on the first pass. We have been unpleasantly surprised more than once, for example by the carbon intensity of crop-based biofuels when we recognized their effect on forests far from their production and the demand they induce for additional fertilizer to increase yields of everything.

A carbon charge is good, but not a magic bullet. First, the same careful science is required to figure out what it should be for this and that; second, it leaks even with a tariff, and third, lots of important ways to conserve, like bike paths, are public goods an individual cannot buy no matter how strongly motivated by more expensive gas.

Yes, I remember that whole cloth v disposable diaper thing, which for all I know is still going on somewhere. These questions are not easy.

It seems to me, we need a cap and trade and maybe a tax too. It occurs to me that there ought to be some magical way to convert, say, student loan debt into some kind of way to leverage people into these new technologies earlier than they would otherwise be able to afford, but I realize that that’s probably some magical thinking on my part. (But my guess is there’ll need to be something done about that anyhow.) We need to get some muscle behind all this, I don’t know how. Rebates only work on people who have the cash to buy the thing in the first place.

And while I’m talking out of my hat here, my other enviro daydream is that we figure out a way to send solar energy from SoCal up north, so that they will forgive us for taking “their” water. And maybe this could even happen without covering up the desert. Meanwhile, in LA, they don’t do those energy agreements for MFH yet. But at least there is a program.

This credible-looking trade site provides a lifecycle carbon footprint of 30g CO2 per kwh for solar, against a UK average for electricity of 451g: one-ninth. UK insolation is less than anywhere in the US south of Alaska, and the share or renewables in electricity generation higher, so the US ratio will be even better. Solar in particular is still a young industry, and is getting more efficient all the time. For instance, the very energy-intensive silicon refining process is likely to shift from vapour deposition - invented to meet the much higher purity needed for semiconductors - to more economical good-enough metallurgical refining methods under active development.

It’s worth remembering that in terms of carbon inputs, the solar and wind fabricators are merely fairly typical subsets of the general manufacturing economy. As that gets more efficient and lightens its carbon footprint, using more renewable electricity and substituting electricity for oil and gas, so will they.

If you want to make a green lifestyle statement rather than doing the boring sums, you really have to go for a pure EV, a Leaf or Tesla. Hybrids, even plug-in, are so oughtsy.

Mind you, there are good practical reasons why pure evs will displace hybrids sooner rather than later. Increased power density in batteries and a richer network of fast recharging stations will eliminate range anxiety for all but a handful of rural Westerners. Getting rid of the ICE and associated gear (gas tank, fuel pump, exhaust, cat converter) saves a lot of weight, space, material and complexity, and therefore cost. Designers work better with a clean slate.

The NREL website is the place to go for general US trends on renewable energies - not the hidebound EIA. For the consumer, the US isn’t a single market except for cars, so I doubt you can find a national consumer-oriented site that covers all relevant comparisons. The NREL online solar calculator PVwatts covers the globe, at lower resolution than the US of course.

Official publications and indices are very slow outside Germany. For instance, Japan just released solar installation data to October 2013 - for a country where all systems have to be uniformly registered to benefit from the FIT. Bloomberg estimates China installed 12 GW of solar PV last year, several GW more than any forecast, but that’s not official. If you want up-to-date information on prices and installations, you have to trawl around in the competing reports of private consulting firms and trade bodies.

Thank you so much!!! I am going to have to post about this on FB, which I normally try not to do (yes, I’m paranoid, and no, I don’t think anyone’s actually after me…)

The UK info is nice because my friend visits there a lot.

I am still a rube, but I did hear recently that people are even thinking of ev/hybrids as a way to store solar energy to help the grid, etc etc. Lots of creativity happening, which is good.