If you are looking for some airplane reading, please pick up the latest issue of the Brown Digest of World Affairs. It includes an article on the 24/7 Sobriety program for alcohol-involved offenders. Beau Kilmer and I co-authored it. The article reviews the work Beau and his colleagues have done evaluating the effects of the program and then discusses my work disseminating it to policymakers in the United Kingdom. We also discuss the ideological resistance the program encounters despite its strong evidence of reducing drink-driving fatalities and domestic violence.

The Diverse Rewards of Being an Oblivious Investor

Imagine you set up an automated Twitter account called something like “Inside Investment Advice” and made it alternate every 24 hours between two tweets:

Oh God! Sell! Sell! Sell! Sell!

AND

Oh God! Buy! Buy! Buy! Buy!

You would probably accrue far more followers than you deserve. There seems to be endless demand for panicky, hyped-up advice to TAKE ADVANTAGE OF THIS STOCK TIP NOW OR ELSE YOU WILL BE SORRY!

That’s a reason I love websites like The Oblivious Investor, which recently featured this exchange between a reader and the website creator, Mike Piper.

Q: How often do you calculate your portfolio’s rate of return?

A: Never.

It’s also why I am grateful to Mitch Tuchman (see his investment advice here) who convinced me in the course of one conversation that the people who benefit the most from fund managers who emit a steady stream of advice to sell and buy are fund managers who emit a steady stream of advice to sell and buy.

I am not a financial guru by any stretch, but I am someone whose profession has learned a good deal about how human beings make decisions in the face of complex information under conditions of high emotion. To summarize a complex scientific literature simply: We stink.

That’s a key reason why investment experts like Mike and Mitch preach that you will almost always lose money over time if you jostle your investment portfolio every 20 minutes based on the latest tip, trend or tweet. As a psychologist, I can also assure you that in addition to losing you money, it’s a surefire way to make yourself a lot less happy.

The Link Between Overcrowded Prisons and a Certain Drug

Over the past few months, I have given some talks about public policies that could reduce the extraordinary number of Americans who are in state or federal prison. The audiences in every case were blessedly bright and engaged. Yet they also had a broadly shared misunderstanding about how two drugs are related to the U.S. rate of imprisonment.

At each talk an audience member expressed the view that over-incarceration would drastically diminish soon because states were now legalizing marijuana. I responded by asking everyone present to shout out their estimate of what proportion of people currently in a state or federal prison were serving time for a marijuana-related offense. The modal answer across audiences was around one third, which explains the shocked looks that greeted my pointing out that even under the most liberal possible definition of a marijuana-linked incarceration (e.g., counting a marijuana trafficker with 10 other felony convictions as being in prison solely due to marijuana’s illegality), not even 1% of the U.S. prison population would be so classified.

Not wanting to discourage people, I said that there was a different drug that was responsible for many times as many imprisonments as marijuana and for which we could implement much better public policies. I then asked people to guess which drug it was. Give it a try yourself (answer after the jump). Continue Reading…

Promote Faculty Based on Where They Work, Not Where They Don’t

Like most professors, I often serve as an external referee when other universities are deciding whether to promote one of their faculty members. Although I’m glad to take on this important role, one line in the cover letters of some promotion review packets makes me highly uncomfortable: “as part of your review, please inform us whether this candidate would be promoted to the same rank if s/he were at your university”. I fear that this question is neither wise nor fair, for two reasons.

(1) Many Metrics of Professorial Success Vary with Institutional Mission

Diversity of structure and mission is one of the strengths of the ensemble of U.S. universities and matches the needs and aspirations of the diverse population they serve. One institution of higher learning may focus heavily on providing undergraduate education to young people who are the first in the family to go to college, while another focuses more on scholarship and still another on professional education to adults with established careers. What faculty are expected to do, quite appropriately, varies in response to such differences in institutional mission.

Stanford University — or indeed any one university – therefore shouldn’t be taken as the measure of all things in faculty promotion decisions. I was promoted at Stanford but there are other institutions where I would not deserve promotion because I am not very good at the core activities they ask their faculty to undertake. Likewise, someone who would probably not be promoted at Stanford could be the pluperfect professor at another institution with a different mission.

(2) Even for Common Metrics of Success, Opportunities to Achieve Differ Across Institutions

A promotion committee chair might respond to the worries I have just articulated by saying “Yes, institutional missions can vary, but our university values research, for which standardized metrics are available to help external reviewers judge fairly whether our faculty would be promoted at their equally research-oriented university”. Type and impact of peer-reviewed publications, grants garnered and scholarly awards received can indeed be compared from professor to professor and from university to university. But it doesn’t follow that faculty research success perfectly reflects whether promotion is warranted because of the varying opportunities universities offer their professors.

For example, a large, urban university affiliated with a public hospital presents faculty with scholarly challenges and opportunities distinct from those of a small, rural institution affiliated with a state agricultural extension service. More generally, wealthier universities like Stanford can facilitate professor’s research success more than can less fortunate institutions (e.g., by offering protected time for scholarship, high-tech research equipment and larger networks of accomplished colleagues in one’s area).

When I am asked to judge if a faculty member with X level of research success would be promoted at Stanford, the counterfactual hangs in my mind: If they were really at Stanford, might they have received more research opportunities and as a result succeeded at a 2X or 3X or more level? If so, isn’t it unfair to hold them to our standards when they didn’t get the resources my Stanford colleagues and I receive to support our scholarly work?

Institutional Worries About Promotion Standards Shouldn’t Be Tackled Within Individual Cases

Some people might argue that despite the fact that universities ask different things of their faculty and have differing levels of resources to help faculty achieve, it is still reasonable to ask external promotion referees whether a candidate would be promoted at the referee’s university as a check on community norms, i.e., “Tell us whether our university is holding candidates to widely-accepted promotion standards”.

I don’t buy it.

If a university’s leadership feels that its expectations of faculty are fundamentally wrong-headed or out of step with national trends, that’s certainly a problem worth engaging. But the appropriate place to engage it is absolutely not within the context of promotion decisions about individual faculty who were told when they were hired to meet their own university’s standards rather than someone else’s. If a university is articulating the wrong standards or not providing the resources required to meet them, that’s not the fault of any individual professor, it’s a systemic challenge the administration must take on.

In the meantime, I hope promotion committees will stop asking referees about whether their faculty deserve promotion somewhere else and just worry about whether they deserve promotion where they actually work.

Weekend Film Recommendation: Railroaded!

I have praised Anthony Mann’s many noir westerns with Jimmy Stewart here at RBC, but have never recommended any of his more traditional urban noirs. Let me rectify that by pointing you to his 1947 low-budget triumph, Railroaded!.

I have praised Anthony Mann’s many noir westerns with Jimmy Stewart here at RBC, but have never recommended any of his more traditional urban noirs. Let me rectify that by pointing you to his 1947 low-budget triumph, Railroaded!.

The film opens with a high-voltage portrayal of a blown stickup, as some luckless bad guys fail to get away clean while robbing a gambling joint, despite having inside help. But the heart of the story comes after the opening fireworks, as the lead gunsel (reliable bad guy John Ireland) and his boozy floozy (Jane Randolph, who excelled in these kinds of roles) frame an innocent man (a sympathetic Ed Kelly) for the crime. A police detective (a pre-Leave it to Beaver Hugh Beaumount) at first isn’t convinced that the guy in the frame is innocent, but he is persuaded to investigate by the attractive, goodly sister of the accused (Sheila Ryan). Action, suspense and romance ensue.

This film was made on Poverty Row, which churned out low-budget B-movies until its business underpinnings were destroyed by the Paramount Supreme Court Case, which I have written about before. The budgets of Poverty Row studios were too small and the films were shot too quickly to consistently achieve quality, but these studios were also a playground for talented people who went on to better opportunities later, including Anthony Mann. The Poverty Row studios were also more comfortable pushing the envelope with the censors, an example in Railroaded! is that when the slatternly Randolph and the saintly Ryan meet in this movie, they get into an extended brawl! (Nice touch by the way: They were dressed in inverted colors for the fight, Ryan all in sinful black, Randolph in angelic white).

Railroaded!, in addition to being an exciting story on its own terms, shows how skilled filmmakers can overcome low budgets. The noir lighting and plenty of closeups keep the viewers from contemplating the cheap props and sets. And Mann’s brisk pace (the film is not much more than an hour long) stops anyone from thinking too hard about some of the less plausible aspects of a script, which would have benefited from one more rewrite to iron out some plot contrivances.

By the way, Hugh Beaumont isn’t the only person in this tough, dark crime movie who went on to inordinately wholesome TV stardom. Ellen Corby, who later became Grandma Walton, appears uncredited as Mrs. Wills.

In summary, this is a remarkably solid and entertaining movie given that its budget was probably around two bits. I believe the poverty row studio movies are in the public domain at this point, so I am posting Railroaded! right here for you to enjoy.

Never a Better Time in U.S. Mental Health Policy?

Did the period from early November through early January comprise the most remarkable advances in the history of federal mental health policy? It’s a defensible argument. To learn why, check out my latest post at Stanford School of Medicine’s SCOPE blog.

U.S. Marijuana Possession Enforcement Intensity is Down Over 40%

Future historians of drug policy will appropriately regard the recent legalization of recreational marijuana in Washington and Colorado as a significant reduction in U.S. law enforcement’s role in cannabis regulation. Yet that marijuana enforcement policy shift had been underway for a lot longer than many people realize.

The chart below presents 2007-2012 FBI Uniform Crime Reports data on marijuana possession arrests and National Survey on Drug Use and Health data on aggregate days of American marijuana use*. To put the two lines on the same scale, aggregate days of marijuana use are reported in 10,000s. The most striking feature of the data are that the two lines are going in opposite directions. The net result is a 42% decline in marijuana possession enforcement intensity (i.e., the number of arrests per day of marijuana use).

Americans’ marijuana use went up by almost 50% just from 2007-2012. This sharp increase in the population’s total days of use has been driven less by the increased number of users than by the big increase in the number of individuals using heavily (e.g., smoking every day or nearly every day). That growth in use meant there was a large increase in police opportunities to arrest people for marijuana possession. But marijuana possession arrests have instead been falling as numerous states have passed decriminalization laws (with for the first time in U.S. history, no White House opposition) and/or created loosely-regulated medical marijuana systems.

The data in the chart support at the least three conclusions about marijuana policy:

(1) U.S. Marijuana possession enforcement intensity had become light even prior to the passage of legalization in two states. As of 2012, the average American once-a-week pot smoker would expect to be arrested for possession about once every century. This reality isn’t evident when one focuses just on the number of arrests, or on how arrests compare to some irrelevant standard (e.g., number of arrests per minute or the percentage of all drug arrests that are for marijuana).

Conclusions about how intensely a crime is being policed can only be drawn in the context of information on how often that crime is committed. Six hundred fifty thousand arrests is a big number in the abstract, but relative to over 3 billion days of marijuana use, it’s small. That why the U.S. can have a large absolute number of marijuana possession arrests yet at the same time be policing marijuana at a less vigorous rate than do most developed nations.

(2) There is no evidence of “net-widening” in U.S. marijuana enforcement policy. In some regions, such as New South Wales, Australia, reduction in criminal penalties for marijuana use led to an increase in arrests. Apparently, Australian police officers who previously felt penalties were too tough began feeling comfortable widening their enforcement net to intervene in more cases of marijuana use. This phenomenon has not been replicated in the U.S., where severity of penalties and number of arrests have been falling in tandem.

(3) Changes in official marijuana policy are often a formalization of what has already been evolving on the ground. The creation of recreational marijuana markets in Washington and Colorado (with some other states likely to follow) is in one sense qualitatively new. Yet it is also the culmination of an established trend of rapidly declining law enforcement involvement in the regulation of marijuana. That’s one reason why it’s often hard for observers to determine whether new drug laws have a unique causal effect or are more a ratification of informal policies that were already in place.

*My thanks to Dr. Beau Kilmer and his team at RAND for providing me with days of use data.

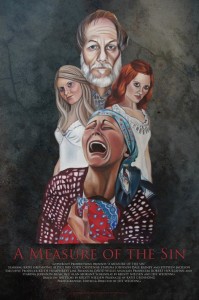

A Measure of the Sin is Coming to Austin and Atlanta

Fresh off of being named one of the best independent movies of 2013 by FilmBizarro, A Measure of the Sin has been made an official selection at two more upcoming film festivals:

Fresh off of being named one of the best independent movies of 2013 by FilmBizarro, A Measure of the Sin has been made an official selection at two more upcoming film festivals:

The Days of the Dead Festival in Atlanta, February 7-9.

AND

The RxSM film festival in Austin, Texas on March 6.

Reviews, list of awards and trailer are all on line here.

Here’s a recent review by Mark Krawczyk which I found very perceptive

On Shutting Off Blog Comment Sections

A few months ago, the editors of Popular Science’s blog announced the following change in policy:

Comments can be bad for science. That’s why, here at PopularScience.com, we’re shutting them off.

It wasn’t a decision we made lightly…we are as committed to fostering lively, intellectual debate as we are to spreading the word of science far and wide. The problem is when trolls and spambots overwhelm the former, diminishing our ability to do the latter.

More recently, the bloggers at The Incidental Economist (TIE) largely followed suit:

All TIE admins are in agreement that we need a break from comment moderation. It’s a lot of work and the benefits relative to costs have dwindled. We’d rather use our time in other ways.

Andrew Sullivan makes his own case against comment sections here. Although I failed to find it when I googled just now, I am pretty sure that some of the bloggers at Outside The Beltway have publicly questioned the value of comment sections, though their site still has one.

I have been ambivalent about this issue for some time. At RBC, we have some absolutely terrific commenters (I saluted some of them here) who add tremendous value to the site for commenters and bloggers alike. At the same time, we also have accrued, it pains me to say, a bad reputation for our comments section being vitriolic and fact-challenged on some topics, most particularly drug policy but also some others (anything about guns usually gets ugly fast).

Can’t bloggers just closely monitor comment sections and separate wheat from chaff? Given unlimited time, yes. But even for the few people who make their living by blogging, time to do this is not unlimited. And for those of us who have demanding day jobs, it’s an awful lot to ask.

Last week, I had a twitter exchange with Austin Frakt about what TIE had done, in which he defined destructive comments as a collective action problem that he was tired of trying to solve. This resonated with me. I was also struck that when I emailed a group of our very best commenters and asked whether we should close off comments on drug policy posts, the modal response was that they didn’t care because they had been driven away from reading those comment sections.

I was sad to hear that and recognized that a negative feedback loop had developed: As a few commenters were abusive or intellectually dishonest or both, those initially more numerous commenters who were civil and substantive began dropping out of the conversation. These two trends reinforced each other until being abusive and non-substantive became more the norm (though some heroes and heroines soldier on, God bless you all).

I do not speak for RBC as a whole on this, but I have come to the conclusion personally that the TIE approach of making a lack of comment sections my default on future posts is the best one for me. There are significant costs to this decision because some excellent comments that would have been made will no longer grace our site. I hope those of you who have for so long contributed reasoned, respectful and data-based reactions, critiques and counter-arguments to my posts will continue to do so on those that remain open for comment.

Weekend Film Recommendation: The Spy Who Came in From the Cold

What the hell do you think spies are? Moral philosophers measuring everything they do against the word of God or Karl Marx? They’re not! They’re just a bunch of seedy, squalid bastards like me: little men, drunkards, queers, hen-pecked husbands, civil servants playing cowboys and Indians to brighten their rotten little lives.

What the hell do you think spies are? Moral philosophers measuring everything they do against the word of God or Karl Marx? They’re not! They’re just a bunch of seedy, squalid bastards like me: little men, drunkards, queers, hen-pecked husbands, civil servants playing cowboys and Indians to brighten their rotten little lives.

So says disillusioned British secret agent Alec Leamas (Richard Burton) in perhaps the best effort to adapt a John le Carré novel to the big screen: 1965′s The Spy Who Came in From the Cold. The serpentine plot concerns a burnt-out espionage agent who enters a downward spiral of booze, self-hatred and lost faith after a disastrous mission in Berlin. But then it turns out that Leamas’ decline and despair is a ruse (?) play-acted at the behest of his superiors. As planned, he is recruited by the other side and ends up trying to discredit East German intelligence head Hans-Dieter Mundt (A cold, effective Peter van Eyck). Leamas undermines the ex-Nazi by feeding false (??) information to Mundt’s ambitious, Jewish deputy (Oskar Werner, very strong here). It’s a difficult, high-risk mission, but Leamas knows that his boss back home is 100% behind him (???).

This may be the most magnificent performance in Richard Burton’s career, and will definitely please all fans of rotting charm. Drinking heavily in real life at the time, he was willing to expose his own capacity for ugliness and decay in a way that many glamorous stars of his era would not have dared to do. He exudes bone crunching hopelessness and isolation in shot after shot: Leamas alone on a park bench, alone in a bar, alone in his bed, alone chained in a cell. He’s devastated and devastating.

A 15 minute sequence of scenes in Britain is a masterclass in cinematic storytelling. It’s unsettling yet fascinating as Leamas repeatedly gets pissed and wanders through empty streets. Ultimately, he savagely beats an innocent man (Did the filmmakers cast for this part Bernard Lee — M from the flashy, unrealistic James Bond series — to make a point?). His copy book blotted, Leamas is judged “turnable” by the other side. After being released from jail, he is recruited by the Soviets in a sleazy men’s club by an unctuous businessman and a pathetic, gay procurer (Robert Hardy and Michael Hordern, respectively, terrific actors who clearly understood that there are no small roles).

A 15 minute sequence of scenes in Britain is a masterclass in cinematic storytelling. It’s unsettling yet fascinating as Leamas repeatedly gets pissed and wanders through empty streets. Ultimately, he savagely beats an innocent man (Did the filmmakers cast for this part Bernard Lee — M from the flashy, unrealistic James Bond series — to make a point?). His copy book blotted, Leamas is judged “turnable” by the other side. After being released from jail, he is recruited by the Soviets in a sleazy men’s club by an unctuous businessman and a pathetic, gay procurer (Robert Hardy and Michael Hordern, respectively, terrific actors who clearly understood that there are no small roles).

The romantic aspects of the story also work well and become more important as le Carré’s ingenious plot unfolds. Claire Bloom is credible and sympathetic as the British would-be communist “who believes in free love, the only kind Leamas could afford at the time”. Leamas’ lacerating disdain for her naiveté reveals the depths of his own self-contempt: She may be immature in her politics but who after all is the one risking his life and doing horrible things in a struggle over the very same politics?

Rarely has the look of a movie more perfectly captured its mood, and that’s a credit to Oswald Morris. Without any conscious intention, I have recommended here at RBC more films shot by Morris than any other cinematographer. He is a remarkably unpretentious professional who maintained an astonishingly consistent quality in his work for 6 decades (and he is still with us at age 98). It was a bold and brilliant choice to make this movie in black and white, which let Oswald create a washed out look that matches the bleak tone of the story. As much as the excellent acting, what stays with the viewer are Oswald’s shots of complete desolation both during Leamas’ alcoholic, putatively free, British wanderings and his time in East German captivity.

The other delight of this film is that it never condescends to the audience by over-explaining. With each double and triple cross, rather than clumsy exposition director Martin Ritt simply gives us Burton’s face, as the mind behind it struggles frantically to make sense of the latest shift in the icy wind. A small example of the film’s understated, even at times cryptic, storytelling style is the scene where Werner asks for some paperwork from his underling Peters (Sam Wanamaker, memorably creepy). The seated, lame, Wanamaker extends his hand but not far enough. Rather than step forward, Werner waits until Wanamaker struggles to his feet and hands it to him. Burton starts to laugh derisively. The subtext which the film expects you to understand: Werner is the boss but as a Jew, he will never be fully respected by his German underlings. A small moment, a sly moment, a powerful moment, brought across with no comment other than Burton’s mad laughs at Wanamaker’s expense.

Touches like that are a key reason why The Spy who Came in from the Cold is completely engrossing. Fans of spy films simply cannot miss this landmark movie.

p.s. If you like this movie, you might enjoy prior RBC posts on the best effort to adapt le Carré to television (Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy) and on the battered, shattered Richard Burton and his iconic dingy overcoat