You’ve watched the scene countless times before, so much so that it’s known by a common trope: The ‘One Last Job.’ The gangster protagonist, with his career of crime behind him, has retired to a more sedate life. This new life offers a different kind of satisfaction – the banality of providing for one’s family, perhaps, or the simpler pleasures of legitimately acquired leisure. And yet, a figure from the character’s criminal past re-appears and coaxes our protagonist back for that One Last Job.

You may have seen it performed by Andy Garcia in Things to Do in Denver When You’re Dead (1995), or Morgan Freeman in Unforgiven (1992), or Robert DeNiro in Heat (1995), or Daniel Craig in Layer Cake (2005). But in each of those films, the scene in which the protagonist is persuaded to return to his criminal life acts as a footnote in the larger trajectory of the film; it’s a happenstance that directors dispense with quickly to get on with the real business of the film’s plot. Not so in this week’s Movie Recommendation, Jonathan Glazer’s Sexy Beast (2000).

The film begins with an opening shot of Gal, played by Ray Winstone, enjoying indolent retirement in Spain with his wife and two close friends. Gal is the kind of character with which Winstone has become synonymous; he is foul-mouthed and gruff, yet still possesses that inimitable East London charm. He languishes at the poolside with his wife – herself a character with a rich backstory to tell – played by Amanda Redman.

The film begins with an opening shot of Gal, played by Ray Winstone, enjoying indolent retirement in Spain with his wife and two close friends. Gal is the kind of character with which Winstone has become synonymous; he is foul-mouthed and gruff, yet still possesses that inimitable East London charm. He languishes at the poolside with his wife – herself a character with a rich backstory to tell – played by Amanda Redman.

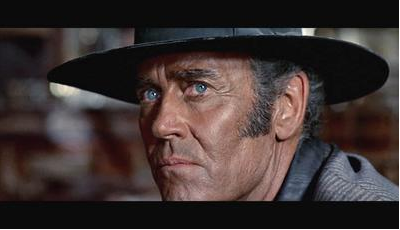

But news arrives that an old companion from Gal’s former days is flying in from England tomorrow. Don Logan, in what remains one of Ben Kingsley’s finest performances, is the equally foul-mouthed capo of the gang to which Gal belonged. Unlike Gal, however, who has been softened by the Spanish sun, Don is a callous and mean-spirited man who does not sympathise with Gal’s desire for a quiet life. More to the point, Don has One Last Job for which he needs Gal’s help.

The rest of the film deals with Gal’s efforts to dissuade Don from bringing him back to England to do The Job. Tensions mount, and tempers flare. The remainder of the film is a thorough treatment of the complex character development that other films relying on the One Last Job conceit overlook, and it is superb.  Don is vicious and unpredictable, Gal is pathetic and desperate, and the film provides a compelling portrait of a monumental battle of wills.

Don is vicious and unpredictable, Gal is pathetic and desperate, and the film provides a compelling portrait of a monumental battle of wills.

At various moments throughout the film the plot meanders a little. This is especially so towards the end, once it becomes clear that relatively little has actually happened. However, the ending is well worth the wait, if only to watch Ian McShane deliver his outstanding performance as the mob boss Teddy Bass.

The film is interspersed with metaphors that capture Gal’s anxieties and neuroses with varying levels of subtlety: the opening scene shows Gal’s tranquility disturbed by an unexpected boulder; the eponymous Sexy Beast plagues his dreams with nightmares relating his impending doom; and the brightly coloured Spanish scenes become gradually more etiolated as Gal begins to realise that his resolve is vastly outgunned by Don’s sheer obstinacy. Regardless, Glazer does a fine job in his first attempt at directing a feature-length film.

Trivia time, RBC. Name other films that feature the One Last Job trope. The rules: One Last Job is specifically about gangsters. Entries about heroes/law enforcement officials nearing retirement or revisiting a pre-retirement case are excluded from consideration. Therefore, films like Lethal Weapon, Blade Runner, The Incredibles, or High Noon (etc.) are out of the running.