Defeat in Vietnam, the OPEC oil embargo, Watergate, rising crime rates, and the first signs of the collapsing blue-collar economy marked the mid-1970s as among the toughest periods in American history.

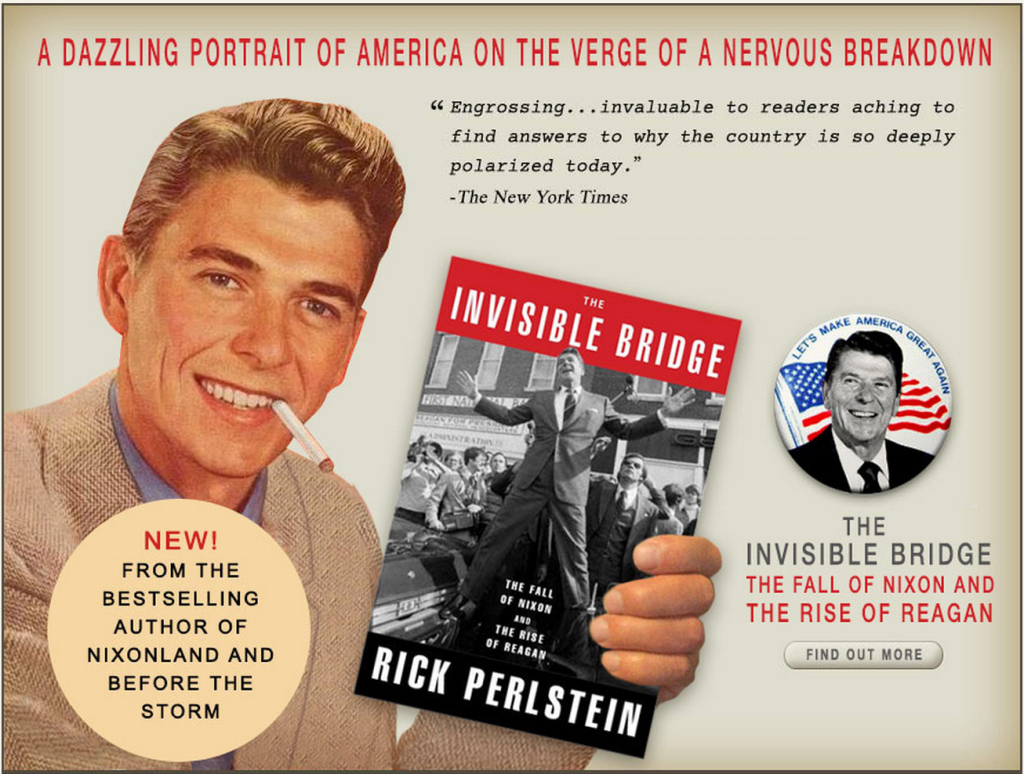

Rick Perlstein’s current best-seller, Invisible Bridge, chronicles that time. It portrays the rise of Ronald Reagan from the Nixon presidency’s Watergate demise to the bitterly-contested 1976 Republican nomination fight between Reagan and then-incumbent president Gerald Ford.

I interviewed Perlstein for the Washington Post’s Wonkblog section. For reasons of space, not all of our conversation was posted. Below is an edited transcript of what didn’t fit within the Post. I think it’s pretty interesting: The FBI, Ford vs. Reagan, the legacy of Martin Luther King, the Manson family.

The life of an independent historian

Harold Pollack:  You’re one of the few historians who’s doing this work in a free-standing way. You’re not a professor. You’re a writer. That’s a difficult path. I can’t say I know too many other folk who are able to do that.

Rick Perlstein: Â Yeah. There have been some challenges. Luckily, I’m now in a very stable place and have been able to put together a solid living doing this. I went to graduate school. I was in a Ph.D program in American Studies. It was much more oriented towards abstruse academic stuff. I really wanted to reach a wider audience. I moved to New York and got into journalism.

HP: The style and sweep of this book does reach a wide audience. Its infusion of popular culture within a broader narrative has reminded several people of William Manchester’s The glory and the dream. It’s a very long book, but it actually reads very quickly…..

RP: You’re not the first person to note the similarity, actually. But I’ve never read that Manchester book. Taylor Branch’s Parting the Water series on Martin Luther King was the real role model among serious books that made me think, “Oh, I want to do a big 3-book series.” It used the biography of a single figure to tell a story about the broader political culture.

HP: One criticism of your book, is that Ronald Reagan, as a person, is less interesting than Martin Luther King….

RP: Less interesting than Richard Nixon!

The FBI’ depredations

HP: One of the weirder moments of the 1970s was when Bernadine Dohrn and some others on the violent left getting a certain vicarious thrill out of the Manson family’s crimes.

RP: That was part of it, too. You have this incredibly bizarre two-week period in September of 1975, in which, there’s one assassination attempt by a woman-which was something traumatic about that in itself-who was a Manson family follower. She wanted justice for Charles Manson, which meant freeing him, because he was seen as this noble guy. Two weeks later, another woman takes a shot at President Ford and wants Patty Hearst to be freed. It’s not only these crazy things are happening and these harbingers of madness, but these lunatics have constituencies….

Patty Hearst was able to stay on the lam for a year, because there was this underground support network of people who thought that she was doing something really cool, when she robbed a bank and said her parents were fascist insects that were preying on the heart of the people.

HP: An irony of this period is the way the FBI combined the sinister and the incompetent as it chased after the Weathermen and others. Some of those they chased after were people just exercising their normal rights. Others were actual criminals or terrorists. The FBI was not very good at the job of actually catching the people setting bombs, even though the FBI spent a lot of time worried about the political threats from less violent people.

RP: That’s another forgotten part of the 70’s: how the malignancy of the FBI, the CIA, and this thing no one had heard of, the NSA, were exposed in these series of House and Senate hearings. People remember the Church committee. There was also this poor prophet without honor, Otis Pike. He was a congressman from upstate New York who led extraordinary hearings in the House about the CIA. They proved not only that the CIA was running assassination squads against foreign leaders, but that the CIA was incompetent at gathering intelligence.

Otis Pike revealed that the week before the Yom Kippur War, the CIA had announced to the president that he could expect peace in the Middle East. It really speaks to what we’ve been going on with the intelligence agencies. The reason they go after these whistle blowers isn’t so much as they claim, that sources and methods must be protected, but that they’re hiding their own incompetence.

Martin Luther King

As far as the FBI goes, November 20, 1975, was an important day in the book for two reasons. That’s when Ronald Reagan announces officially that he’s running for president against Gerald Ford. It’s also the day that the Church committee uncovers that the FBI had sent a dossier to Martin Luther King of transcripts from their bugging of him. They sent a poison pen letter designed to try to get him to commit suicide after he’s named a Nobel Laureate.

How they come together in the book is this: Ronald Reagan gives a press conference at the National Press Club announcing his presidential campaign. One of the reporters asked him what he thought of the news that morning, that the FBI had done this. You remember Reagan’s answer?

HP: I do not, but it was not a positive one.

RP: He said that he hadn’t read the papers that morning. It was like: “no comment.†This blithe affect in the face of what others considered chaos was, to my mind, central to his appeal.

HP: Later as president, Reagan was once asked whether King was a Communist during the debate over the King holiday. Reagan said: “We will know in about 35 years.†(He later apologized for that comment.)

RP: This is a favorite subject of mine- conservative attempts to co-opt the memory of Martin Luther King. When Dr. King was assassinated in 1968, Ronald Reagan said, and I quote it in Nixonland, basically that King had it coming: “It’s the sort of great tragedy when we begin compromising with law and order, and people started choosing which laws they would break.” In other words, How can you say: “It’s okay to sit in the middle of the street, when that’s illegal and tell an assassin that he can’t follow his views?†That was Reagan’s interpretation of civil disobedience.

He signed the Martin Luther King holiday when there was no political alternative, but this idea of wishing away conflict and that he could do it with such confidence, when everyone else was so ambivalent, was pretty remarkable.

Of course, there were other appeals. Many people responded to Reagan’s small-government appeal. But I mean look: Gerald Ford issued dozens of vetoes and he was a real small government conservative. He was probably the most conservative president we had, certainly in generations. A scholar, a political scientist did a study at the 1976 Republican Convention that I cite over and over, in which he interviewed people and said, why do you support Reagan and why do you support Ford? No one said: “Reagan thinks we should have lower taxes,†because Ford thought we should have lower taxes. It was all: “Reagan radiates this confidence and Ford radiates this diffidence and nuance.â€

Reagan vs. Ford

HP: Some might regard Ford as a tragic figure in the book. He’s this plodding guy who ends up as president through this circuitous route…

RP: Because he’s mediocre. Because he could get confirmed because he hadn’t made any enemies. Because he took no risks.

HP: All of a sudden Ford’s challenged by Ronald Reagan, in a way that no incumbent President expects to be.

RP: Reagan is so good at pinning Ford into a corner rhetorically because of Ford’s responsibility for governing a country and having to make compromises. I always say, being a president in the 70’s, you’re damned if you do, damned if you don’t.

That’s one of my refrains. When it comes to the Panama Canal—which was really the issue that Reagan almost rode to the Republican nomination-All these people were saying: “You lost a bunch of primaries. You had your fun, now get out of the sand box.â€

Anyone who studied the issue from this empirical establishment perspective saw that the Panama Canal Treaty had never even been looked at by a Panamanian before it was signed. It was a true artifact of high imperialism. Panamanians were rioting regularly, because they had this imperial force right in the middle of their country—which had been invented in order to break it off of Columbia. Ronald Reagan comes up with this refrain, “We built it. We paid for it. It’s ours.”

He promoted this idea that somehow the establishment, Harry Kissinger in this case (whom, by the way Reagan had supported down the line when the Nixon administration was in office) was somehow selling off America, piece by piece. That they’d be giving up Omaha next. Reagan really struck this post-Vietnam mood. People really wanted to believe that nothing could keep America down, even reality and facts and geo-strategic calculation.

HP: It’s striking how Nixon quieted the extreme right while he was in office.

RP: He did. The conservative movement doesn’t even show up in Nixonland. That’s because he did such a good job in making them a non-factor in American politics.

Past and current conservative populism

HP: It’s natural to compare the Tea Party with the earlier followers of Ronald Reagan. How does the current Tea Party movement compare o the earlier rise of the new right that you chronicled?

RP: As you know, I am very big on the continuities within American right-wing populism, at least since The New Deal. I think the biggest difference is the sociological infrastructure, based in Washington and northern Virginia, that’s so good at identifying and leveraging grass roots complaints. It’s so good, and so sophisticated. That was completely different. Although one of the stories I tell concerns its emergence.

Another difference is the ability of business interests to leverage the conservative movement to anti-Keynesian politics, when big business had been the spine of the Keynesian approach and the post-war social contract.

Another difference is that the mainstream media has become professionalized in a way that legitimizes any planting of a flag by a right-wing politician as a poll in the debate. As they plant their flag further and further to the right, not only the media, but also Barack Obama, legitimate it as a responsible negotiating position. Which means that the center goes further and further to the right, as ratified by the forces of the establishment. That’s a big difference.

The John Birch Society was coming out in 1961 and saying pretty much the same things the National Review saying now, even though the John Birch Society was kicked out of the pages of the National Review. Â In the early 60’s, the John Birch Society was considered this quasi-fascist formation that was a danger to the continued civic health of the country.

There was a cover story on the John Birch Society in Time magazine, which basically treated its positions as illegitimate. I compared them in one of my essays to Time magazine’s cover profile of Glenn Beck, which followed one a couple years earlier about Ann Coulter. It wasn’t: “These people are tearing apart the fabric of America,” it was, “Wow. Look at these interesting people. Aren’t they interesting?”

HP: I agree with you that there is no gatekeeper function in the same way today… There’s no way to marginalize the extreme right in quite the same way it was in 1960.

It’s also true that the not-so-extreme right was saying some pretty shocking things. If Americans today went to the library and start reading back issues of the National Review from the late 1950’s or early 1960’s, most people under the age of 50 would be rather shocked. Maybe the John Birch Society was marginalized. What was not marginalized was straightforward support for segregation and other policies that are not permitted in respectable conversation today. Glenn Beck is not standing up and saying what William Buckley was saying: explicitly defending the disenfranchisement of African-American voters.

RP: No, Beck’s talking about the disenfranchisement of Arab-Americans instead. The frontier of which groups are included in the national conversation, and which are excluded, keeps on changing. There’ll always be an other to hate. Some talk about the idea that the Muslim brotherhood is literally infiltrating the White House and taking over the decision-making process apparatus in the state department. That’s very much parallel to what we heard about African-Americans and Communists in the 1950’s.

HP: I think that we are a more liberal society in 2014. You have to go out to people like Ann Coulter to find things like that today.

RP: Consider: We have a Supreme Court justice who’s most reactionary. He’s a black man married to a blonde woman, which was a lynching offense in our lifetimes. I can imagine a Supreme Court justice married to someone of the same sex, voting twenty years from now to outlaw the minimum wage. I’m not sure that’s progress….