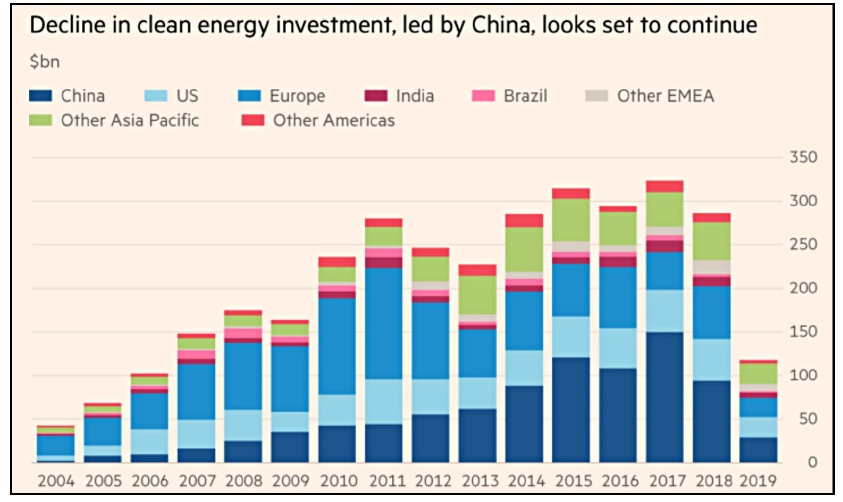

Bad in two senses. From a recent post by Kevin Drum with the scare headline “The World Is Giving Up On Climate Change”, a chart from the reliable FT:

Looks terrible! But Kevin truncated the FT chart – the 2019 bar label has the important subscript “H1”. (FT article, paywalled – trust me, I got a sneak view somehow, and it’s definitely there.) The all-year total won’t be great, but it will be fairly close to last year’s ca. $290 bn.

Why would Drum, normally a thoughtful and careful blogger and a chart maestro, make a silly mistake like this? I suggest it’s motivated reasoning. Drum has locked himself into the untenable positions that the energy transition requires large and very unlikely changes in lifestyles, that existing technologies are too expensive, and that the only hope is massive R&D to find something much cheaper. These three positions are nonsense (see for example Jacobson, Blakers, Breyer (pdf), or for the tl:dr capsule, me). To defend an untenable position, you grasp at straws. Look, the FT says renewable investment is collapsing! Only it isn’t.

The chart does tell us a less dramatic, but still real, bad news story. Renewable investment was growing fast until 2011, then the boom stopped and spending has been stuck on a plateau. The effect has been mitigated by the continuing falls in the prices of wind, solar and storage. Lazards give a 10 year decline to 2019 in the costs of wind in the USA as 70%, of utility solar 89% (13th survey of generation costs, pdf, page 8); they don’t supply a trend for storage, as the use cases are so varied, but do note a fall in costs. Price trends are global. So annual renewable installations have been growing in GW terms, only not as fast as they should.

This is not what Econ 101 would lead us to expect. When a technology steadily gets cheaper than its rivals, the rate of adoption should speed up, as investment shifts from higher-cost incumbents to cheaper newcomers enjoying economies of scale and learning. Following the classic logistic curve, the rate of substitution eventually slows as you near saturation, but renewables are only near that today in a few small countries (Norway, Denmark, Costa Rica).

We have to ask: what happened around 2011 that flipped renewable investment from growth to stagnation?

It certainly wasn’t a halt in technical progress or a global recession

– the GFC was essentially over by then. I can see only one

candidate: the victory of austerity policies over Keynesian ones.

This was driven by ideology over good economics, and supported by some very sloppy analysis (as with Rogoff’s debt limit argument). The austeriacs won because their message was congenial to financial elites, and required cuts in public spending and transfers to the working classes. As in the 1930s, the victory was temporary, and a new wave of populist right-wingers (Trump, Johnson, Abbott) rose to power who don’t care at all about financial orthodoxy. But it was for a while complete enough to secure a rollback in the incentives that had enable the rapid growth in renewables of the 2000s. Germany led the way with the EEG “reform” of 2012, and was followed by Spain and the UK. Renewable investment only restarted in Spain last year, with a socialist minority government and a determined environment minister.

This is not a complete explanation, and does not account for the Chinese cutbacks, which came as late as 2018. Xi is probably not a fan of Alesina and Rogoff, and Chinese policy firmly supports growth and full employment. However, fears of the unsustainability of renewable subsidies can also arise in a controlled economy. In the USA, the self-blocking design of the Constitution and the spectacular incompetence of the Trump Administration have limited the rollback to largely symbolic changes like the waters regulation.

There is another suspicion, which fully applies to China. The fossil fuel industries are large and effective lobbyists for their businesses, to which the renewable transition is an existential threat. It would be astonishing if their minions did not use the austeriac arguments to hand, with superficial academic credibility, and playing to the prejudices of the policymakers they are dining with. Some fossil fuel tycoons – notably the Kochs – reinforced political lobbying by shoring up congenial academic research, notably the Kochs’ support of the Mercatus Center at George Mason University in, importantly, Washington. And is Harvard squeaky clean here, with its massive investments in fossil fuels and a lax policy on donations?

Don’t forget that the fossil people had and have a large direct interest: the subsidy rollback was specific to renewables, and the old subsidies to fossil fuels, buried deeper in the tax code, escaped unscathed. The change was a reverse Pigovian tax, a public policy in favour of pollution.

Someone joked that there are two theories of history – cockup and conspiracy. Cockup is the default, and works for some major events like the French and American Revolutions and the start of the First World War. But conspiracies are sometimes real and effective, as the careers of such luminaries as Lenin, Hitler, the Kochs, and bin Laden attest: all the way back to John of Procida, the likely mastermind of the Sicilian Vespers in 1282. I have a pet theory that the seizure of Brill by the Dutch Protestant Sea Beggars in 1572, nominally following the closure of Dover to them by the English to placate Spain, was in reality a deniable black op of Francis Walsingham’s.

I can’t prove the hypothesis that the energy transition was kneecapped by a conspiracy of fossil fuel lobbyists using bogus austerity arguments. But it’s worth investigating.

If that’s so, a suitable sanction for the perps could IMHO be life in a gulag, somewhere like here.

Disproportionate you say? What’s proportionate for the crime of procuring genocide for hire?