I love museums. Science museums, history museums, art museums; there’s nothing like looking at real stuff in person. Whether it’s an antique automobile, a big old beetle in a case, or the Ardabil carpet in the V&A, being able to walk around it, get close, and engage on my own time is one of my top-level pleasures. I’m sure I learned as much natural science in the American Museum of Natural History as a child as I did in school; whenever I’m traveling, I make a beeline for local museums.

The affection is not entirely requited in art museums, mainly because so many of them transparently disrespect me (and all the other visitors) by pointless, insouciant, arrogant stinginess with the information that makes the art accessible. This weekend I was at the Huntington, the Getty Villa, and LACMA in LA. The Huntington and the Getty do a pretty good job with long, informative labels that provide context, history, and some guidance about what to attend to in the works on display, but LACMA left me really steamed.

A featured exhibition was several galleries full of contemporary political art by Iranians that reached back to the Shahnameh for analogies and references, a show with appropriate local interest (there are lots of Persians in LA, including refugees from before and after the shah’s overthrow) and in any case an interesting and fruitful concept. You should go and see it, but unfortunately you will miss a lot unless you’re already hip to recent (and ancient) Iranian history, and can read Farsi. The labels were tiny and short and one after another very political work full of incriptions, signs, and text in Farsi was untranslated. One faceplant in particular seemed to sum up art museums’ worst instincts to make not only the typical visitor, but almost any visitor, feel unqualified and inadequate.

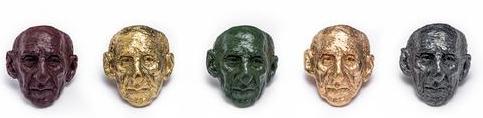

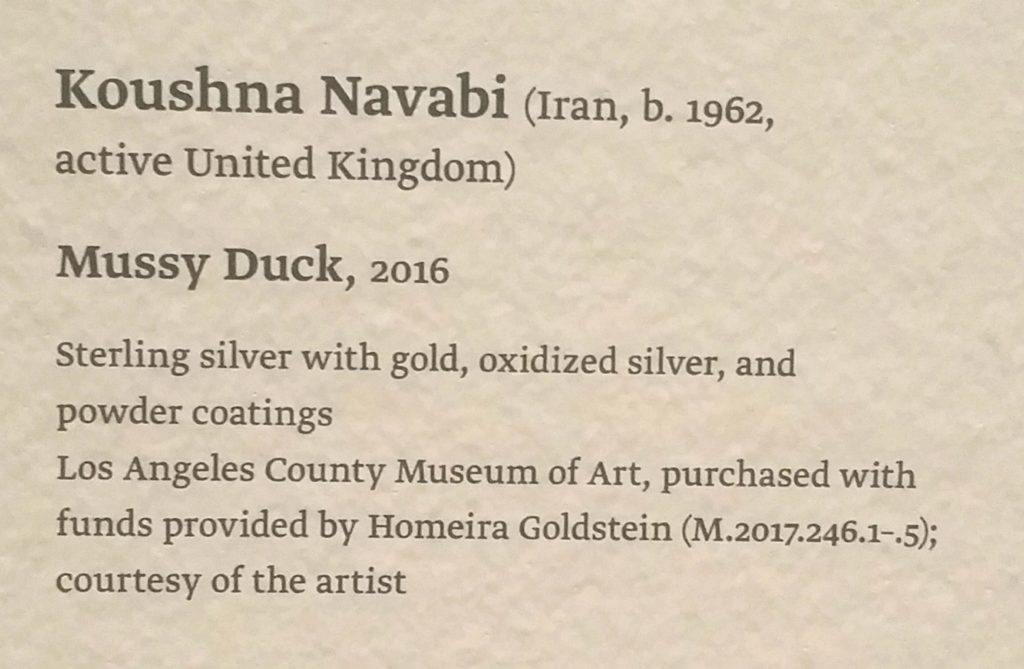

The work, by Koushna Navabi, is a couple of dozen rings in different metallic finishes with the same portrait, a little over an inch each way:

This is the entire label we were offered:

Know whose portrait this is? Only because I’m old enough to almost remember the period, and spent some time in Iran after the coup that overthrew him, I recognized Mohammed Mosaddegh, about whom Wikipedia says “Many Iranians regard Mosaddegh as the leading champion of secular democracy and resistance to foreign domination in Iran’s modern history. Mosaddegh was removed from power in a coup on 19 August 1953, organised and carried out by the CIA at the request of MI6.” In the oppressive regime of the shah and his SAVAK secret police that followed, Iran’s oil remained in the hands of western oil companies and their US and British protectors. Of course by 1979 this arrangement went off the rails because the Iranians had had enough of it.

Any of that useful in engaging with this work? Or is the (I presume) affectionate but rather obscure pun in the title all you needed? I hung around and asked at least a half-dozen visitors if they knew whose portrait was on the rings; none had any idea. Here’s what the curator thought she was doing with this show; I’m sure her middle-east specialist colleagues were impressed, but an exhibition like this is a lot of work: I guess she just didn’t have a minute to actually think about the visitors who would walk in the door.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.