Part of the fallout from the Elizabeth Warren-Donald Trump tweet feud is the reintroduction of Warren’s contested claims of Native American ancestry. Without getting into the details of Warren’s claim, with which I am unfamiliar, this provides an opportunity to discuss how such claims are established (at least with respect to five tribes).

The National Archives maintains a website for researching Native American heritage with various historical documents. In this post, I’ll focus on the “Five Civilized Tribes in Indian Territory” (Cherokee, Creek, Choctaw, Chickasaw and Seminole) listed on the Indian census known as the Dawes Rolls (1898-1914). The “Five Civilized Tribes” are the tribes that were forcibly resettled into Oklahoma (many on the Trail of Tears); being listed on the Dawes Rolls was proof of tribal membership and entitled one to an allotment of land. Of course, even these historic rolls depended on accurate recordkeeping and accurate initial assessment, which was difficult given the circumstances. Careful recordkeeping was but one casualty of the genocide of Native American people.

The Dawes Rolls (and similar materials) now matter for those seeking to establish a claim of tribal membership. The Archives has a helpful tutorial that shows users how to track their ancestors using the example of a man named Napoleon Ainsworth, a member of the Choctaw tribe.

As it happens, Napoleon Ainsworth was my grandmother’s grandfather.

I grew up hearing about my native ancestry and about Napoleon Ainsworth in particular: how he served on the Tribal Council, how he studied law at UVA. I had no doubts about this ancestry: I knew I was related to my grandmother and knew that she was a descendant of her grandfather. This was, of course, just a part of my ancestry, but I know more about this great-great grandfather than any of my other great-great grandparents. I’d also like to carve out some space in the discussion between all or nothing—for “some” identity. It might be a small part of who I am, but it’s a part of me nevertheless.

Even as I knew this, I didn’t have any official relationship with the Choctaws. It didn’t seem to matter: my mom and my aunt were both official members, which is appropriate given the Choctaws’ matrilineal tradition. Eventually, though, I wanted my own membership, but given the potent cocktail of both familial and governmental bureaucracy, it took time to send in the paperwork necessary to become a member of the Choctaw nation—until 2014, actually. (Good things come to those who wait and ask repeatedly for several years.) And this is what I want to talk about: what proof looks like, and how strange it feels.

A new form of identity?

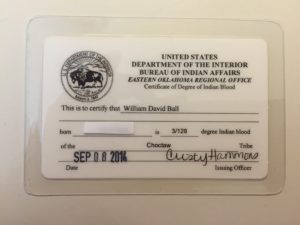

This is a photo of my Certificate of Degree of Indian Blood (CDIB) from the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Once my paperwork was processed, I received it along with some other materials, including my membership card in the Choctaw nation and an official CDIB number that is now part of a federal database of those with documentation of native ancestry. When I got these materials, I was pushed and pulled. It was bizarre to receive notification of native ancestry from a federal bureaucracy, a notice that I was officially a “blood Indian.” It seemed the antithesis of sovereignty, the big brother government telling me about an antecedent culture. Or maybe the CDIB number makes me more like a specimen in a collection, subject to population management. In any event, I now had the official paperwork that allows me to participate in tribal governance.

So this is what proof looks like, and I am at least part of the picture of what a contemporary member of the Choctaw nation looks like. The point of this is not for me to claim to speak for anyone or to claim a cultural and racial authenticity. I don’t and wouldn’t. I am overwhelmingly something else besides Choctaw (having less than 3 percent “Indian blood”, though this is enough for Choctaw membership). In some ways, the diluted nature of this ancestry is part of the legacy of the U.S. treatment of native people: their cultural, geographic, and racial dislocation and destruction. I am part of the Choctaw smithereens scattered throughout the country by governmental policy. I’m just an echo of what was. (Or, if you want to be optimistic, I’m a living legacy of the melting pot.)

But the notion that native identity—like any other kind of racial or ethnic identity (or, frankly, many other kinds of identity)—is somehow fixed or simple or resolvable in a series of tweets and countertweets is absurd. After hundreds of years of contact, removal, intermarriage, smallpox blankets, cooperation, and betrayal, there are no easy answers, just difficult questions. I’m not a pure anything. Lots of people with “Indian blood” have other kinds of blood—so did my ancestor on the Dawes Roll, Napoleon Ainsworth. It’s not absurd to think that Elizabeth Warren has some Native American blood—and again, I’m not saying she does, nor am I denying that native cultures and claims of authenticity have been appropriated well before this (it’s why I will never go to a Flaming Lips concert again). But, in some ways, the way in which she has been attacked, being called Pocahontas (or Fauxcahontas) implies that there is some native identity trapped in amber, that authenticity is necessarily premodern (even though I get my Choctaw news via Facebook), that “real” Indians look like the Indian who cried during those 1970’s litter commercials (even though he was entirely of Italian descent).

This would be a great opportunity to interrogate what Elizabeth Warren meant by her claims to native ancestry—what currency that had, what proof would look like, or what it would mean in terms of how we do or should see her. What is our concept of Native Americans now? What is the self-concept of various first nations? It would also be useful to interrogate what Trump is objecting to (behind the insults) when he asserts that she isn’t “really” Native American. What does that mean to him? (And is he really that concerned with authenticity?)

What I’d like to suggest is that concrete answers are hard to come by, given the intentional campaign to destroy Native American identity and culture. You can’t burn the house down and then complain about how fragmentary the evidence of the original structure is-or denigrate the inauthenticity of what gets rebuilt. And even if we did have concrete answers, they wouldn’t necessarily be satisfying. The concept of “real” race and its relationship to blood is a recurring obsession in American political culture (think of the “one drop” rule destroying whiteness). In the case of native ancestry, what’s different is that blood is what’s measured, and the federal government issues you a racial identity card that tells you how much blood you have (perhaps pushing the question to how much is enough, or whether identity might have at least as much to do with community and culture as blood). For me, my own CDIB card was just part of my ongoing process of identity. It didn’t give me information I didn’t already have—it simply gave the BIA information it didn’t have about me. I already knew Napoleon Ainsworth was a Choctaw, and that he was my great-great grandfather.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.