With the exception of a few choice gems, it’s commonplace that sequels don’t ‘live up’ to the legacy they inherit from the earlier film. In this weekend’s movie recommendation, I’d like to submit that Scorsese’s sequel to Robert Rossen’s The Hustler (reviewed here), in which Paul Newman reprises the role of ‘Fast’ Eddie Felson to train up the young hotshot Vincent Lauria in The Color of Money, deserves to be placed among the great sequels.

It’s been twenty five years since Fast Eddie left behind his life as a hustler working his way up the ranks under the tutelage of the devilish Bert Gordon. He’s fashioned a life for himself that allows him never to stray too far from the seedy dive bars he left behind, but only in a capacity as a liquor salesman. Fast Eddie’s mouth remains just as quick as before, and Paul Newman always has that glint in his eye that betrays the self-assurance of a man who knows he’s the smartest guy in the room.

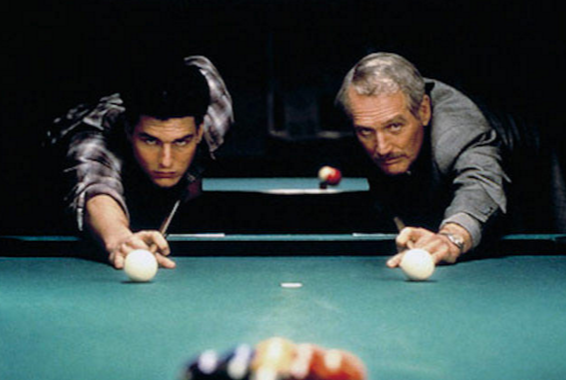

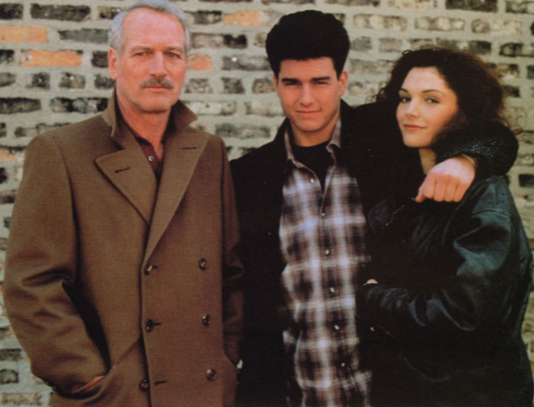

Eddie happens upon Vincent Lauria, played by Tom Cruise, who suffers from the same unrefined skill Felson brought to a pool table when we met him on screen two and a half decades earlier. Vince is cocksure, dashing, and in dire need of Felson’s guidance. Eddie zeroes in quickly to the fact that Vince is highly susceptible to the persuasions of Carmen, played by Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio, and he maneuvers himself into their collective good graces to hatch the plot of his career: Eddie, whether he knows it or not, wants back in the game, and Vince and Carmen are his ticket.

So, in an only loosely veiled form, Eddie re-creates the same power dynamic that destroyed his own life many years earlier. Replacing Bert as the villainous guide with plans of his own, Eddie has a fiery determination to get it right this time around. Vince, too, has a stylized symmetry to the Eddie of yesteryear: in both characters, the people around them see a ‘thoroughbred race-horse’ that has to be cared for and manipulated to do as told and make a buck. Yet that manipulation rarely translates into sympathy for the pool shark involved; instead, we just become infuriated when Vince, just as Eddie before him, allows his impetuous hubris to sabotage whatever intricately planned hustle they were on the cusp of completing.

Carmen appears to resemble her earlier version (Piper Laurie’s Sarah Packard) the least among the main trio in The Color of Money. Unlike the frail Packard, Carmen is empowered, independent, and intimidating. She is a frighteningly quick learner—Eddie, therefore, soon realizes he has to out-maneuver her lest Vince disappear out from under his own puppeteering.

The stylization in Color of Money is also quite a departure from The Hustler. Instead of Rossen’s lingering shots and close-ups, patient use of camera and sound, and extended dialogues, Scorsese harnesses the dynamism that had brought him critical acclaim in his recent films Taxi Driver and Raging Bull. It wasn’t until Color of Money, however, that Scorsese also managed to secure commercial success. Quite rightly, too: he was able to rein in the stars into a format that appealed to a wide audience, the eclectic soundtrack is engaging, and there’s a confidence in the movement between symbolically pregnant scenes—evocative of the same heavy allegory that permeated The Hustler—to downright frivolous and fun pool hall chicanery.

There are even some stellar cameos, from Forrest Whitaker and John Turturro, on the trio’s rise to the top. But what really makes The Color of Money so satisfying to me, and what earns it a place in my mind as one of the great sequels, is the payoff in the very final scene. I can’t suppress the massive ear-to-ear grin across my face just before the credits roll.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.