If you have to wait for further instructions, you might as well wait somewhere enjoyable. Bruges will do.

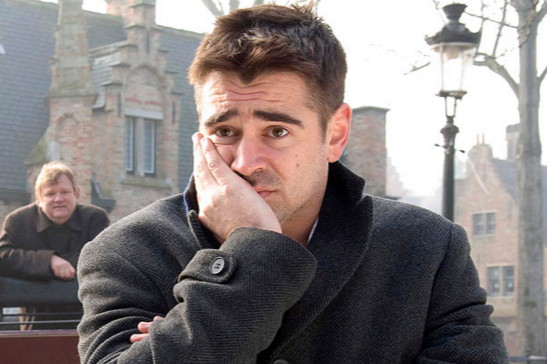

Hitmen Ken and Ray just finished a job in London, and their boss Harry has told them to hide out in Belgium until he sends further word. The snag, however, is that although Ken (played by Brendan Gleeson) is perfectly happy to soak up the sights in this beautifully preserved medieval town, Ray (played by Colin Farrell) can’t stand it. At all. This week’s movie recommendation is about their troubled stay In Bruges.

Ken and Ray don’t really look much like hitmen. At least they don’t look like the kind of hitmen we’ve come to expect. Neither do they stand out in slick suits (e.g., Michael Mann’s Collateral) nor are they identifiable by a meticulously-crafted Gaultier not-quite-everyman aesthetic (e.g., Luc Besson’s Léon). No, these two really are quite inconspicuous—banal, even. Yet they both have their own kind of affable charm to them: Ken is the avuncular senior partner among the duo, and Ray is the oafish malcontent battling inner demons that are revealed as the story proceeds.

It turns out that Ken and Ray are under a mistaken impression. They have not been consigned to pass their time in Bruges indefinitely as they wait for Godot Harry to provide them with some glimmer of purpose. Rather, Harry has sent them to Bruges so that Ray may enjoy his final days before he assigns Ken to tie up loose ends from the last job by killing Ray.

In a nod to writer-director Martin McDonagh’s theatricality, In Bruges contains an abundance of Easter eggs that weave together tight plot points in a manner uncommon to most films. It’s not common you’ll find the macabre—yet exquisitely funny—image of a man assigned to kill his partner, yet so racked with guilt that he’ll interrupt the target’s efforts to kill himself upon discovering that suicidal ideations are soon to take care of the assignment. It’s also not common to find the play-within-a-play conceit used to provide not only commentary on the main plot, but also as a necessary feature of the film’s denouement. There’s even a Chekhov’s gun moment, as Harry (played by Ralph Fiennes) hesitatingly purchases dum-dum bullets only to resolve all the film’s loose ends in the most unexpected manner.

For all of the clichés, McDonagh does a fine job handling the audience’s expectations in such a way that the plot is a surprise from start to finish. Followers of the weekend movie recommendations will have noticed that this is neither McDonagh’s first film reviewed here (see my favorable review of Seven Psychopaths, which sees Colin Farrell well cast in a similarly troubled role), nor is it the first film to which his name is attached (see his hand in The Guard, which was directed by his brother and which also starred Brendan Gleeson). But although In Bruges is McDonagh’s debut feature film, it sets up all the same themes that unite his later works, too: redemption, fantasy, and shame, all of which are embedded within a neat send-up of tired film tropes.

McDonagh’s principal talent is in exploiting audience misdirection, and this is apparent both in his storytelling as in his humor. The comedy frequently veers toward—without transgressing—the macabre and uncomfortable. Nothing’s off the table: the jokes always set aim (although rarely clearly so at the outset of the joke) at racism, xenophobia, ableism, alcoholism, mental illness, and, and, and. But there’s a quality to the humor in In Bruges that echoes what made The Guard so successful. McDonagh enjoys playing with the audience’s misapprehension that what appears as one thing is in fact another altogether. It’s the audience’s discomfort while we’re figuring out where on Earth is this headed? that makes In Bruges so compelling to watch from start to finish. As far as debut feature films go, it just doesn’t get better than this.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.