. .. but not yet.

Declaration of the G7 on climate change, 8 June, my italics:

Mindful of this [2º C] goal and considering the latest IPCC results, we emphasize that deep cuts in global greenhouse gas emissions are required with a decarbonisation of the global economy over the course of this century.

The 85-year timeframe that was all they could agree to has attracted righteous scorn from climate scientists. Kevin Trenberth:

Decarbonization by the end of the century may well be too late because the magnitude of climate change long before then will exceed the bounds of many ecosystems and farms, and likely will be very disruptive.

Michael Mann:

In my view, the science makes clear that 2050 or 2100 is way too far down the road. We will need near-term limits if we are going to avoid dangerous warming of the planet.

Sure. It’s still a landmark, an Overton shift, that leaders at this level have spelled out that the goal isn’t a 40% or 50% or 80% reduction in human carbon emissions, it’s stopping them completely. Everybody can understand this. Bye bye coal, bye bye oil, bye bye gas. Like Augustine’s self-reported prayer “O Lord, make me chaste, but not yet”, the G7 have conceded the principle. The rest is just timing.

Activists should note that the declaration was drafted by professionals. Over the course of this century isn’t the same as by the end of this century, and carefully leaves the door open to an earlier target.

The beauty of the full decarbonisation goal is that it immediately generates the full list of problems to be solved and new technologies needed. It’s impossible not to use some oil for petrochemicals? The residual usage will have to be offset by sequestration. Once you have robust sequestration options, the door is open to going carbon negative, as James Hansen insists.

The top of the list is obvious, and under way, if not fast enough.

- Efficiency: check.

- Cutting out coal for power generation: check.

- Rolling out solar and wind generation: check.

- Electric vehicles: check.

The LLNL energy flowcharts show that electricity and transport between them use two-thirds of US primary energy, so these are the big ticket items.

I am getting a little bored with just cheering on solar, wind, electric cars and buses, and smart controls, and I expect that goes for my readers. Some of the smaller problems lower down the list are technically more difficult and interesting. They include deforestation, aviation, shipping, steel-making, and cement. So let’s get started.

In my next post, I have a suggestion on cement.

CharlesWT says

At the moment, nuclear is the only energy technology that has any chance at all of scaling to the point of making an significant replacement of fossil fuel use.

James Wimberley says

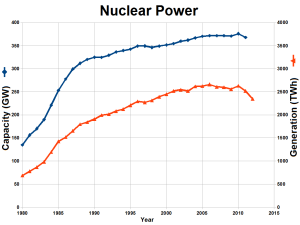

A chart from Wikipedia of global nuclear capacity and generation that speaks for itself:

There is absolutely no chance of nuclear power making a significant contribution to the energy transition. It was given a good shot, and has failed. Nuclear advocates may say that it’s all terribly unfair: voters have irrational attitudes to objectively very low risks, spooked by the few accidents, and in consequence regulators have gone paranoid. The scale-back has led to loss of human and institutional capital, so even the French are in a deep mess at Flamanville. But these are facts too.

Give up. Join the renewables party. Our stuff works, tomorrow. Even the EIA is coming round.

CharlesWT says

If renewables are the only alternative, then you're stucked. There's no way in the near to midterm future that they will scale to fill current energy demands. Never mind future energy demands as third and developing world countries strive for something approaching first world living standards.

JamesWimberley says

Global pv solar installations were at least 40 GW last year (estimates vary), wind 51GW. Using a 20% capacity factor for solar and 35% for wind, that makes 8 GW continuous equivalent and 18.9 GW. Together, they are equivalent to 30 hypothetical 1-GW reactors. Net nuclear capacity is not increasing at all - it may pick up a bit in the next few years as a very few of the 67 reactors under construction come on line, all in China, but there is no real growth overall. Solar companies plan capacity growth in half-gigawatt units. New wind turbines come in at 3 MW on land, 8 MW at sea, on 100m towers. What's your proposal for Mali: a string of reactors along the bend of the Niger?

joel hanes says

Today, Iowa gets one third of its electricity from wind power.

RhodesKen says

Iowa? Hmmm…54,000 square miles, with plenty of open areas where nobody objects strongly to wind farms, supporting 3 million people. How will that scale to New Jersey or Massachusetts?

Please note-I'm NOT saying we shouldn't be pushing strongly for wind and Sun energy. I'm just saying you can't cite one example and suppose you've made your case. It's complicated, and it's hard, and it takes a lot of communal commitment.

KatjaRBC says

In its current shape, I see nuclear energy only as a transitional technology. The once-through fuel cycle with the fairly minimal amount of nuclear reprocessing we have would run us out of nuclear fuel within decades.

What we need for sustainability is (1) better reprocessing technology and reactors that can utilize reprocessed nuclear fuel and (2) the ability to effectively harvest uranium from the oceans. But that's both more expensive and currently as much pie-in-the-sky technology as anything else.

On top of that, we need a solution for the entire world, not just rich countries. I'm not just talking about affordability (which economies of scale should be able deal with), but the gigantic proliferation problem this would create. A world that relies almost exclusively on nuclear energy almost by definition has to be a peaceful world with a good amount of shared prosperity.

But if we can get to such a world and assume a matching level of technological advancement, then renewable energies become even more of an option. For example, there's little doubt that an energy union that spans Europe and North Africa could easily live off renewable energies; it would also be great for Africa's economy. The reason why this is a problem is the lack of political stability in Africa.

In the short term, we are also dealing with non-trivial economic constraints. Germany isn't burning vast amounts of lignite because it is good for the environment, but because it is dirt cheap (no pun intended). Back in the day, France could built the amount of nuclear reactors they have only because they poured a ton of government subsidies into the effort, something that's no longer possible under the EU's state aid rules without getting an exemption (see what's going on at Hinkley Point for an example). And France did it because it is a country severely lacking in resources (much of the historical conflict between France and Germany was due to the coalfields in Lorraine and the Saar area, and the European Steel and Coal Community, a precursor to the EU, was created largely to put an end to this type of conflict). What's keeping the EU (somewhat) on track towards carbon reduction is their cap-and-trade scheme that specifically ignores the economic self-interest of the member states, not any national policies that may or may not be beneficial. This is also something where rich countries have to lead and stop whining about China, because we can afford to trade a bit of GDP for the future of our planet (fun fact: if I use my bike to get to work rather than our car, I'm technically hurting the economy).

Neither nuclear nor renewable energies will be able to solve all problems, though. We still need some sort of portable fuel for shipping and air travel. Railways can substitute for airfreight to an extent and short to medium personal travel, but I still don't see batteries working out for trucks or driving long distances; and there's the whole sector of maritime shipping, which has a huge carbon footprint. Biofuel or hydrogen may be able to substitute for some uses, but that's still a ways off.

Brett says

Hmm. With aviation I see two possibilities:

1. Offset: The percentage of CO2 being emitted into the atmosphere from air travel is comparatively small, so you might be able to offset it completely. Have planes run entirely on biofuels, then replace whatever is grown to produce those biofuels in order to draw out an equivalent amount of CO2 from the atmosphere. The airlines and plane manufacturers seem confident that they could drastically reduce air travel emissions with biofuels, if they're cheap enough.

2. Hydrogen: This is much more radical, but you probably could run a plane on hydrogen instead of more conventional fuels. Engines for it exist, and experimental planes using hydrogen fuel have been built. There's a trade-off, in that the cooling requirements of hydrogen make the plane bulkier, but the use of liquid hydrogen also makes it a lot lighter.

James Wimberley says

Why stop at the Sabatier process when you have Fischer-Tropf to get you all the way to the liquid fuels you know and love?

Brett says

It's definitely one of the routes, and the more likely one in my opinion since it means you wouldn't have to throw out tons of established infrastructure and jet engine design to replace your jet-fuel planes with hydrogen ones.

Keith_Humphreys says

Hmmm…I lack your expertise in treaty formulation, but I am afraid even your somewhat sceptical read may not be sceptical enough. You are imputing the world "total" before "decarbonisation", but they didn't put that word in (And I know the elves ponder and slave over every word of these declarations). Just as a depopulation can mean reduce rather than eliminate a population, the word here would seem to leave room for some reductions and not elimination of carbon, e.g., "We have decarbonised as we promised: we emit 25% less than we did a century ago".

James Wimberley says

Good point. I missed that. The natural reading of “decarbonisation” implies “full”, but you can certainly argue the other way. Canadian sherpa: “Leave out “full”. German sherpa: “In that case will you accept “in the course of?” “Deal”.

Such declarations are not treaties, but as you say they are carefully negotiated, and stake out positions and boundaries for treaties. Canada will be more isolated in Paris than at the G7, where it is ridiculously over-represented. A lot of delegations in Paris will be pressing for “full”.