In this week’s movie recommendation, Tom Tykwer’s independent German film Lola Rennt [Run Lola Run], you’re corralled through one of the most frenetic and high-octane interpretations of the butterfly effect conceit ever put to the screen.

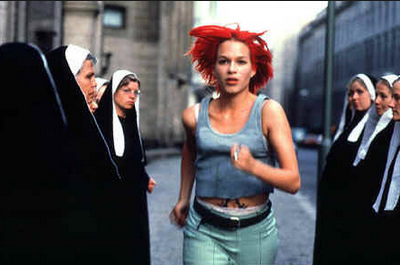

The story begins with Lola, a fiery red-headed woman played by Franka Potente, receiving a phone call from her distraught lover Manni (played by Moritz Bleibtreu). Manni has botched an assignment that he hoped would initiate him into Berlin’s organized crime gang headed by Ronnie (played by Heino Ferch). In particular, Manni has misplaced a bag that was filled with 100,000 of Ronnie’s Deutsch Marks, and he has to produce the delivery in twenty minutes else he’s a dead man. Can Lola save the day?

Everything in Tykwer’s representation of Berlin is heavily stylized. The film’s main premise has barely been set up before we’re assaulted with techno-music, split-screens, color-switches, and cartoon sequences. It’s an intentional sensory overload, and it’s relentless until the film’s 81st and final minute. This fanciful stylization fits neatly with the general improbability of the film’s premise. Tykwer adds yet another layer of stylization, however, by introducing the most video-game conceit available: Lola has three lives to make this work. Each twenty minute attempt is replayed from the same starting point when Lola picks up Manni’s phone call, and on each occasion we notice minute differences that play out with momentously different outcomes.

At times, it’s unclear how much of a commitment Tykwer really makes to this video-game conceit. It’s not as though Lola keeps learning from the mistakes of previous attempts as we might otherwise expect, although there are nonetheless some perceptible continuities between episodes (the highly astute viewer will pick up little Easter eggs left in each re-telling that weave together their own little sub-plots). It’s also not clear how much of the departure in outcomes from one episode to the next is attributable to differences in Lola’s actions alone (for example, whether Lola trips over a dog is hardly related to an old lady’s victory on the lottery).

All the same, the video-game-slash-butterfly-effect conceit enables Tykwer to do something that would otherwise be a real challenge with what is essentially a storyline constrained to twenty minute bursts: he constructs characters in whom we become unmistakably and sympathetically invested. This is quite the accomplishment, and it’s achieved in a variety of ways. One is by transitioning to an altogether different medium when representing Lola and Manni’s intimate moments, which are captured in sequences of still photographs rather than video to charge these otherwise ephemeral moments with emphasis and sentimentality. Another is by providing indulgently unnecessary glimpses that project forward into the lives of people who are only tangentially affected by Lola’s actions. In both of these, viewers aren’t just invited to watch the story; they’re gleefully being forced by Tykwer to consume it exactly how he wants you to, which is to say with disoriented intrigue.

That’s why watching each of the three episodes is equivalent to taking a triple shot of espresso, washed down with a can of Red Bull, and rounded out with an open-handed slap to the face. The film’s 81 minutes go by quickly enough, but you’re left without an opportunity to process what’s just happened in front of – or, more accurately, to – your senses. The mere fact that each episode begins by rehearsing an almost identical opening does little to center you as a viewer, and denies you the moments that would be necessary to re-calibrate yourself to new surroundings.

However, while Lola Rennt is disorienting, the pace is thoughtfully conceived; the experience isn’t discombobulating in the way a badly-executed action film sequence, which flits between shots twenty times in fifteen seconds, might be. On the contrary, Lola Rennt is exquisitely composed so that the disorientation is tightly managed and draws your attention through to the next frame, so that we hope for reprieve in the story rather than full resolution. It’s remarkable.

Lola Rennt treads over similar philosophical ground as other films of this ilk: fate, time, chaos, and agency are all joyfully thrown around as though there’s meaning in the questions… but Tykwer knowingly dismisses any invitation to grapple with them in any serious way beyond the existential resignation to ‘let things stand as they must.’ The result is a film that some will find frustratingly shallow, and others will find enjoyably provocative.

schmidtb98 says

Definitely a good flick. A fairly early gender-reversal film too, with the man playing the part of the fair maiden that needs rescuing.