The Hollywood staple in sports films is typically inextricable from some facile metaphor about the American Dream: pure determination predicts real success. Work hard, and you’ll make it on to the team. Believe in yourself, and you can overcome racism. Train hard enough, and you may even defeat communism. Yet for this week’s movie recommendation, in what is possibly the greatest sports film of the twentieth century, iron resolve and the American Way is nothing less than the source of the main character’s complete downfall. It’s Robert Rossen’s The Hustler (1961).

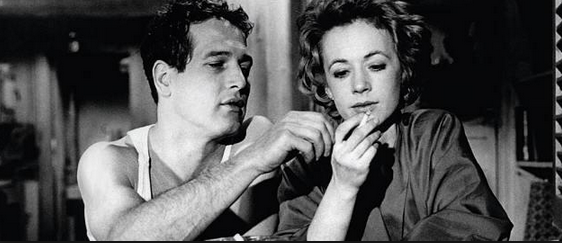

A young Paul Newman plays the dashing ‘Fast’ Eddie Felson, a pool player who fails to understand that his impressive knack with a cue isn’t the same as being able to win. Felson is a small-time hustler with an eye toward playing in the big leagues. His ticket to get there is a victory against the top pool shark in the land, Minnesota Fats (played by Jackie Gleason). After Felson calamitously loses to Fats, he learns that you need a lot more than just an ability to ‘play a good stick’ when you’re the other side of a 25-hour marathon; you need endurance, ‘character,’ and the knowledge that…

This game isn’t like football. Nobody pays you for yardage. When you hustle, you keep score real simple. At the end of the game, you count up your money. That’s how you find out who’s best. It’s the only way.

During Felson’s spiral into despondency, he betrays his close friend Charlie (played by Myron McCormick) and falls into both the loving arms of Sarah Packard (played by Piper Laurie) and the dastardly machinations of gambler Bert Gordon (played by George C. Scott). Although Bert at least has the decency to tell people that he’s making a buck at their expense, the hustles are in fact ubiquitous. Indeed, the deceptions have become such a way of life that the distrust infects even Sarah and Eddie’s relationship. If Eddie is going to beat Fats, it’s going to come at the expense of whatever innocence he has left – or that he might hope to recover through his connection to Sarah.

Sure enough, at one point Eddie has to scrounge a cash stake by sneaking money away from Sarah during her own period of acute vulnerability, as she is drunk and unconscious at a stranger’s home. The choice between either protecting his love or pursuing his game is made as easily as it was earlier, when he similarly betrayed Charlie.

Bert’s incomparable wickedness means that he is only too happy to facilitate Eddie’s demise. He sees Sarah as an inconvenient distraction from Eddie’s ability to earn money on his behalf, and he effortlessly dispenses with her with little more than a few well-placed barbs. The screenplay thankfully devotes ample attention to the important sub-plot between Bert and Sarah. The impressive power-play between these two characters forms of one of the most affecting scenes, when Bert returns to the hotel before Eddie, fresh from their most recent hustle, and seduces Sarah after Eddie’s recent betrayal. Between Bert’s connivances and Eddie’s negligence, Sarah doesn’t stand a chance.

During the final showdown with Fats at the film’s denouement, we see exactly where Eddie is headed. The chasm that separated the two characters at the beginning of the film has disappeared: in Fats’ perpetual expression of resignation (Gleason’s eyes betray palpable melancholy), we see that he, too, has been broken down by the years of hustle – he is as much a victim of Bert’s extortion as was Eddie. Fats doesn’t need to hide that he’s the best in the business; instead, the form that his indignity takes is that the hustle has reduced him to one of Bert’s props. Fats sits by and listens as Bert and Eddie exchange verbal blows, familiar as he is with the waltz the two are dancing – he’s done it himself. It’s the dance of people giving up their souls to the hustle.

Rossen’s adaptation of the Walter Tevis novel of the same name thankfully doesn’t suffer from Felson’ hubris: the direction is admirably restrained and deftly executed. However, at times the religious allegory is piled on pretty thick (for another instance of this, see Newman’s performance in Cool Hand Luke, reviewed here). Not only is Felson’s search for redemption a preoccupying theme but the reverence for the hustle and its participants is positively ecumenical (the hallowed billiard hall in which Eddie will battle with Fats is the “Church of the Good Hustler”). If the Manichaean characters aren’t yet abundantly apparent, Bert is compared to the devil during the scene immediately preceding his consignment of Sarah to oblivion, whereas Eddie’s thumbs are broken as crucifixion for the sin of having hustled inexpertly.

The Hustler garnered nominations – but no awards – from the Academy for all four of its main cast members. I’ll soon review the sequel from two and a half decades later, when Newman earned his only Oscar – reputedly in apology for having been passed over in The Hustler.