From time to time we hear about concierge medicine. It’s always interesting, if a little frustrating, because it either polarizes people—to some it’s a model of the future; to others, a scourge—or is met with a long yawn. Maybe it’s my enthusiasm for the larger topic of physician reimbursement, but I always find it’s a model that points to larger, more significant issues that do warrant attention. And this is particularly when someone actually has a number (rarely). It gets to the heart of markets in health care. Some argue they should have the freedom to select this model if they can afford it. And after all, the dirty secret of many more equitable health systems is a certain amount of ‘choice’ that quietly occurs for the affluent—it’s just on a different scale in those countries, and miraculously (mostly) kept in check. But is it the solution to our primary care crisis, really? The American Academy of Family Physicians is pretty cautious about this model and rightly points out the access issues that arise from charging large annual fees.

A key question is, what are the incentives for physicians to take this route? A recent survey suggests 6.8% of physicians would “embrace” direct pay or concierge medicine. The article paints a rosy financial future for physicians adopting this practice model. I’m not going to critique the survey methods— I’ll limit my comments to the substance of one article reporting the finding, but, I do question the significant gains in practice profitability. It is likely only a solution for a tiny group of physicians and patients.

The positive spin on concierge medicine of course, leaves aside the sick and complex patients who might want—and need—all the time in the world, and numerous visits. I suspect there is a ceiling on ‘unlimited visits’ —what would happen to the profitability of a practice when more than one patient makes their 90th appointment in six months?

The profitability of this model can’t only be administrative costs—even though everyone loves to slam insurers—it’s more likely explained by the fact that on average, the services are underutilized due to the average risk profile of the patients. The ‘frequent flyers’ need to be a tiny proportion of the roster for this to work.

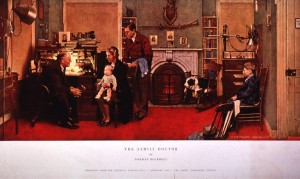

Second, a study Sherry Glied and I published last year in Health Affairs quantified the large gap between US primary care physician incomes relative to specialist incomes in other countries. But maybe the problem with making a living for primary care and specialty physicians alike is not just overhead, but partly efficiency and scale. Concierge medicine is a response, apparently to the fact that the “business model of the independent or small practice is likely not sustainable and they just having a harder time keep[ing[ the lights on.” We might like the idea of a lone Norman Rockwell physician (no one talks about the low overhead of a long-suffering wife doubling as receptionist and book-keeper), with his stethoscope in his leather bag, but integration into larger entities is necessary in many areas of the economy. Concierge medicine responds to the fact that we don’t always like the depersonalization and bureaucracy of large organizations; but large organizations are often required for efficiency reasons. Investments in information technology for one, create scale incentives. Therefore, it’s not really keeping the lights on, but the fact that a larger practice might better afford those lights.

Like many so-called innovations in health care, and policy more generally, it depends on the risk selection and the assumptions about where the efficiencies are. In K-12 education I think we’ve gotten beyond that; many parents will be skeptical of a new model only tested in high SES areas. But in health care policy, sometimes people extrapolate findings, based on a small healthy subset, to the health care system as a whole.

Er, I thought, what is concierge medicine?

Wikipedia has an explanation.

The term is singularly ill-chosen. Parisian flat owners don’t SFIK have a direct payment relationship with the concierge: they pay dues to the condo management, which hires the concierge. The concierge doesn’t look after their individual flats but after the common spaces and services. “Golf club medicine” would at least be clearer.

Is this the kind of thing you had in mind?

I’m 56 and have been seeing a concierge doctor for almost a year now. He charges me $49/month. I think we’ve done two visits, some lab work (really low cost, too) & twice we’ve done tele-medicine for chronic conditions. Granted I’m in good health but all in all this seems to be more cost-effective than traditional health insurance ($600 a month + co-pays) or non-insured office visits ($100+) & the low-cost labwork he negotiated with a local lab is a real bonus as well.

“Some argue they should have the freedom to select this model if they can afford it. ”

I’m really struggling to imagine what moral principle (That dared honestly reveal itself.) could actually argue against people having the freedom to buy better medical care if they can afford it.

The principle, which I would consider moral (in a social or political sense, but even on an individual level), is that one should try to make available equally the best health care one can. If some people can buy more, that takes the providers of the ‘more’ out of the general system, leaving less for those who can’t afford it. Also, and possibly worse, the people who can buy more are often the most articulate and the best at getting what they want from society, so if they are compelled to remain in the general system, they will advocate to keep it at a high standard. If they can opt out, then the general system is likely to deteriorate and no one who ‘counts’ is affected by the deterioration, so it continues.

I think that’s honest and respectable. I know that not everyone agrees with it, and some respectable health care systems (like France’s) allows some opting out.

How does “one”, or even several, “try(ing) to make available equally the best health care one can.”, involve preventing others from doing something else? Do you really suppose health care is a zero sum product, where if I buy better, somebody somewhere ends up with worse than they’d otherwise have?

Yes. Look at the public school system, for example. I’m not saying we should do this, but I think it goes without saying that if every kid went to a local public school, there would be more pressure to improve the product. I don’t think this is either wise nor desirable to implement, but I don’t think it’s arguable.

For health care, where there is, as a matter of fact, a limit (zero sum), taking out any Family Practitioners has a direct effect on the care available to other local people.

Goes without saying that if we shot everybody of above average height, untold billions would pour into solving the problem of hereditary dwarfism. Shall we?

This is just the ancient evil of ‘leveling down’, spite equipped with a new excuse. An evil liberals seem particularly prone to imagining is a virtue.

And, no, healthcare is not remotely a zero sum game, save in the trivial sense that essentially EVERYTHING is a zero sum game when looked at short enough term. As demonstrated by the fact that life expectancies have risen over time.

BRett, “Zero Sum” doesn’t mean that the field will not expand. It is shorthand for limits.

Nor only France, but Britain does. If you have the money to pay for a private Harley Street physician and the London Clinic, you are completely free to do so. There’s no subsidy, or refund if you choose not to use the NHS. I find it hard to imagine a system that denied the right to opt out and pay full whack.

Full whack in the UK is shockingly cheap though. The private walk-in clinic in Victoria Station was 25 pounds. The cost controls within the NHS create an expectation about what care costs, which anchors what private providers can charge.

Full whack in the USA means a bedpan is gold-plated and costs more than the Pentagon pays for it…

This article, on US medical costs, is one of Ezra Klein’s best over the last year:

Why an MRI costs $1,080 in America and $280 in France - The Washington Post

http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/ezra-klein/post/why-an-mri-costs-1080-in-america-and-280-in-france/2011/08/25/gIQAVHztoR_blog.html?tid=pm_pop

And if you really want to talk costs you can’t forget the stinking waste. This editorial in the AARP was probably their best in the last year:

http://pubs.aarp.org/aarpbulletin/201211?pg=4#article_id=220048

The whole damn American Health Care system needs to drowned in a dumpster and recast, reborn, reincarnated…

It’s an embarrassment. It stinks on ice.

Check this out:

According to that AARP editorial, half of American health care professionals don’t even wash their hands when they should.

If that’s not a five star WTF…

What is?

The principle, which I would consider moral (in a social or political sense, but even on an individual level), is that one should try to make available equally the best health care one can. If some people can buy more, that takes the providers of the ‘more’ out of the general system, leaving less for those who can’t afford it. Also, and possibly worse, the people who can buy more are often the most articulate and the best at getting what they want from society, so if they are compelled to remain in the general system, they will advocate to keep it at a high standard. If they can opt out, then the general system is likely to deteriorate and no one who ‘counts’ is affected by the deterioration, so it continues.

I think that’s honest and respectable. I know that not everyone agrees with it, and some respectable health care systems (like France’s) allows some opting out.

Brett, is there anything that you don’t think should be rationed on the basis of wealth? Is that always the the determining factor in how much of anything anyone should have?

I believe you’re misusing the word “rationing”, to the end of defending actual rationing. Which is what telling somebody they weren’t permitted to buy healthcare they could afford would be a genuine example of.

So substitute “allocated” for “rationed” if that makes you feel better.

But answer JMN’s question. Let me try to restate it: Given that there is (in the short run at least) a fixed supply of X, under what circumstances, if any, should X be allocated on any basis other than willingness to pay?

Given a false premise you can prove anything. Not going to play that game.

Or in other word, forced to apply theory to reality. Nope, Brett no playee.

False premise? I don’t think so.

In the short run the supply of doctors is very inelastic, close to fixed.

I’m with Brett on this one. Byomtov: in the short run, the supply of everything is fixed: heart surgeons, iPads, tickets to the Cup Final. Should everything be rationed? In the long run only the supply of the tickets is inelastic. Medical plenty is conceivable, and France, Germany, Japan and Sweden come pretty close. The immediate problem of US health costs is inefficiency, not scarcity.

Interestingly, Brits - even lefty ones - are much more relaxed about private medicine than about private schools, which are seen as giving the children of rich parents an unfair relative advantage, and weakening élite support for public education. In contrast, if the Duke of Westminster wants the gold bedpan, he’s welcome to it. This would change if it were widely thought that the Duke is getting significantly better medical treatment - better drugs, or access to organ transplants - as opposed to comfort and convenience.

I disagree, James.

Yes, the short run supply of iPads is fixed, but it doesn’t take years to expand production. And even if it did no one would suffer unduly while waiting. Neither will the inability to buy a SuperBowl ticket affect anyone’s physical wellbeing. So there is no argument against charging what the traffic will bear in those cases.

I’m not trying to say the whole concierge business should be illegal. Indeed, if my doctor, whom I’ve been seeing for fifteen years or so, went to that sort of practice I’d probably pay up. Still, I do find it a little distasteful, and I dislike the glibness that shrugs off negative consequences and equates medical care with say, getting a haircut. You mention that Brits are calm about private medicine. Fine. But that is in the context of the NHS being in place. We don’t have such a system. If everyone were assured of getting some decent minimum quality of care I also would have no problem with concierge practices or the like.

Medical plenty is indeed conceivable, but until we get it we don’t have it and have to deal with what we have. You say the problem is inefficiency, not scarcity. I take this to mean we have the same number of practitoners per capita, more or less, as other countries, but that somehow their services are delivered less efficiently than elsewhere. Why isn’t the practical effect the same as if there were scarcity?

Markets are terrific for lots of things, but I think the question JMN poses is important - is there anything that shouldn’t just be allocated by willingness to pay?

If it’s a method of determining who gets something and who does not, it’s a form of rationing. In a world of scarce resources, some form of rationing is inevitable. I think that you’re rationalizing in an attempt to avoid dealing with the consequences of your beliefs by pretending that an indirect form of rationing isn’t what it is.

Nope, though that’s a definition of “rationing” that’s very popular among people who want to impose rationing; Just pretend that rationing is unavoidable, and most of the stigma of your plan for imposing it is supposed to go away.

Rationing:

Verb

1 Allow each person to have only a fixed amount of (a particular commodity): “shoes were rationed from 1943″.

2 Allow someone to have only (a fixed amount of a certain commodity): “they rationed themselves to one glass of wine each”.

No, letting people buy all they can afford is not “rationing”. The central concept of rationing is that people aren’t permitted to obtain more of the good. It represents a denial of a good to people who could otherwise get more, in order to enforce equality on people who could do better.

Hiding behind a dictionary definition in order to avoid a discussion is a sorry enough spectacle, but ignoring those definitions that are unhelpful reduces it to pathetic.

From http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/ration: a share especially as determined by supply

Now, would you be happier if I used the word “allocate”? My purpose here is not to get tied up in semantics, though I’m starting to suspect that yours is.

Brett, is there anything that you don’t think should be allocated on the basis of wealth? Is that always the the determining factor in how much of anything anyone should have?

My MD doesn’t take Medicare, so for his older patients the choice is pay on a per-visit basis (the labs would take Medicare, just not the MD) or find another. Out of pocket would work if you stay healthy; if not, the sky is the limit. Can’t see doing this after paying insurance premiums for a lifetime (and not using the services very much).

Darms,

If all you have is your deal with the Doc, I have to wonder what’s going to happen if, God forbid, you or a family member comes down with something that needs operations and hospitalization. After the first half million dollar bill that $49 a month won’t look to have been such a bargain. I found going without insurance very cost effective until I actually needed it.

As to the soi disant concierge model, where’s the need? Although I often hear claims that it is hard to get in to see the Doc, primary or specialist, this has not been my experience. I don’t have a problem getting an appointment, usually within a day or so of calling.

Perhaps this has to do with my heavily doctored Southern Cal location. Or, maybe, it just isn’t that tough in reality (unless you live in a poor, rural area).

I have run into several Docs who wanted me to sign up for the concierge service her in S Cal. But, couldn’t see any advantage to me to paying more to get what I am already getting-good, speedy medical care. Thank you LBJ for Medicare.

One issue that I wonder about is how the idea of paying extra for “better” service interacts with the requirement that Docs take insurance as payment in full for services to the insured.

You need to become more familiar with the concept and the models within it. Read my comment below. The insurance situation, at least in our case, doesn’t change. The fee we pay is to offset the Doctor going from over 2000 patients to 600. But what changes is the access. Many minor questions are taken care of with emails/pictures etc. We can call 24/7. Appointments are same day if needed. We have access to doctors, in the same group, all over the Country if needed when traveling (which has come in handy more than once) There’s no hurry in the office and the longer conversations lead to a better understanding overall.

No one is making anyone do this. So what’s the problem? Well…that’s rhetorical, we know what it is.

1-no kids

2-my wife has decent insurance through her job

3-I have a catastrophic-care insurance policy ~$150/month, only pays for hospitalization but again, I’m in good health.

4-Had a cellulitis flareup, emailed my doctor last night, I’ll see him at 1PM today. Last time I relied on conventional doctors at a local clinic, the wait could be a week or more…

The piece basically ‘beats around the bush’ and only brushes the main reason this model is held in such contempt by some.

“The ‘frequent flyers’ need to be a tiny proportion of the roster for this to work.”

The issue for these folks is that, in these practices, the Physician will only have about 600 patients instead of a more average 2200. It doesn’t take a math whiz to conclude that the more doctors that enter this model the more doctors will be needed overall.

Enter the fear that is associated with the ‘light bulb coming on’ for these folks with the new so called health care law…the dearth of Doctors. You see, once the field of medicine becomes the purview of the government, the sense of ‘calling’ that Doctors historically felt will be gone. In this configuration, Doctors are no longer free individuals but considered “community property” to be distributed ‘as needed’. Being assigned a discipline and location where you’ll live and work was not what they signed up for.

And so, with the proliferation of Concierge Medicine, because of the diminished numbers of people becoming Doctors, it’s necessary to immediately brand the practice ‘exclusionary’, ’boutique’ or some other derogatory term in order to assign to it a stigma that those upon hearing it hate it without having to know what it is.

It will be interesting to see what happens. My wife and I have been in this relationship with our Doctor for about three years. We are both on Medicare and Social Security so we get a chuckle out of those that try to say it’s for “the rich”. The cost is not insignificant but it’s a choice we’ve made…what a word…choice.

Enter the fear that is associated with the ‘light bulb coming on’ for these folks with the new so called health care law…the dearth of Doctors. You see, once the field of medicine becomes the purview of the government, the sense of ‘calling’ that Doctors historically felt will be gone. In this configuration, Doctors are no longer free individuals but considered “community property” to be distributed ‘as needed’. Being assigned a discipline and location where you’ll live and work was not what they signed up for.

Do you have any idea what’s actually in the health care law? This paragraph strongly suggests that you don’t.

Plus the premise of the paragraph is laughable, that serving produces disdain for service.

I’ll see your bet and raise you the house limit: My grandfather got his start in life as a government-hired doctor in a pure socialist program, the CCC. He was sent to the sticks to treat workers in turpentining camps. This meant that he and my grandmother lived in a log cabin with no plumbing in the piney woods, where there were chiggers and she had to draw all the household water from a pump in the yard.

Far from diminishing their sense of public service, the experience honed it. For the rest of his life my grandfather, a university of Chicago educated son of gentility, ministered to poor whites and blacks in a town of fewer than 2000 people. And my grandmother was precisely one of those “long-suffering wives” mentioned above that filled the unpaid role of receptionist and record keeper. Not to mention making sandwiches for patients when the day’s appointments ran late.

Thank god for social security or she would have starved in her last years. Thank god for Medicare which aid for the last fifteen years my grandfather spent in a nursing home.

If someone came out of that early experience without a sense of civic service and obligation, they never had one in the first place. (Anyway, I thought Ayn contemned public service. Why would you propose that any doctor have a sense of calling if civic service is so awful? … And is there some sense of calling I haven’t noticed among modern doctors? Frankly, most recent med school grads, at least the specialists, are primarily in it for the money, as one would expect in a profession where salaries have gotten so insanely high. Doctors’ wives now expect to live like mid-level Saudi princesses instead of a comfortably provided existence.

You tea baggers are a bunch of diaper boys compared to the people they were.

My grandparents, god rest their beautiful souls, had more class and duty and human worth and Jeffersonian ideals and constitutional republic in their fingernail clippings than the whole lot of you.

Someone like your white-trash grandmother probably saw a doctor like my grand-dad in the 1940s and that’s the reason you’re even alive today. You wouldn’t have been fit to to loosen the ties of their sandals.

God bless the welfare state, and fuck you, ducky, all up and down.

Technically the CCC, (Which I will gladly say was vastly superior to the present system of just giving the unemployed money, without demanding labor of them.) was not “pure socialism”, in that nobody was being drafted into the work gangs.

You see, once the field of medicine becomes the purview of the government, the sense of ‘calling’ that Doctors historically felt will be gone.

Prove it. The VA is a government run system and one of its remarkable features is that about 25% of the staff are veterans themselves who have very deep commitment to serving their fellow veterans. And the non-veterans, many of whom are from military families, in my observation share that commitment.

Bill Inaz and his wife are milking the socialist system.

His post is a classic example of “Keep your government hands off my Medicare!”

Idiot teabagger.

” Betsy says:

January 24, 2013 at 8:13 am

Bill Inaz and his wife are milking the socialist system.

His post is a classic example of “Keep your government hands off my Medicare!”

Idiot teabagger.”

Well, that didn’t take long….LOL!!

Having dealt with one French physician as a patient, and knowing two others personally, I’d say that all three have a strong sense of “calling.” Just anecdotal.

Bill, can you explain how this works? You pay $49 a month, and that’s all? And so what happens if, tomorrow, heaven forbid, you walk into your doctor’s office with chest pains, you’re having a massive heart attack and he ships you off to intensive care for two weeks? Or if one of the other of your doctor’s clients has a premature baby that has to spend two months in the NICU? I don’t understand how this all gets paid for. Or what about someone who has chronic, serious asthma or diabetes or cystic fibrosis and is in the doctor’s office every ten days and in the hospital once a month?

Not sure if the question was to me but I would start saying I’m not familiar with the “$49 plan” and share your skepticism as to just how well that might work. As I said, I have and maintain insurance…that doesn’t change. The fee I pay is over and above what that insurance costs us.

Sorry, I meant darms.

So you just pay more, and get better service? Nothing wrong with that, but it doesn’t seem like a solution to anything but wanting better service. I’m giving the long yawn here.

“So you just pay more, and get better service? Nothing wrong with that…”

Glad you feel that way. Everyone makes choices on how to spend their money. Cable TV, Sports, data plans, cocaine and hookers, jet skis…no one begrudges these choices.

Part of my point above is that with concierge medicine, there’s a move afoot to stigmatize it as something where those that choose it are taking something from everyone else.

It seems fairly clear: The $49 a month doesn’t get you the healthcare, you still need insurance or whatever for that. It gets you healthcare from a doctor with relatively few other patients.

Insurance has the leverage to negotiate profit margins of doctors down, so that each individual patient hardly provides any profit at all. But if each of 600 people is paying the doctor’s office $49 a month, that’s $29K a month of pure profit, allowing the office to be a going concern with a fraction as many patients, the insurance covering actual marginal costs, and the retainers paying fixed costs.

Chest pains? I contact my concierge doctor & we decide if it’s hospital time. If yes, I go & (hopefully) my catastrophic-care insurance kicks in if I’m admitted. If not, I’m out for an ER visit. BTW I have chronic asthma but at 56 I long ago learned to control it (that was one of the two chronic conditions I got the tele-medicine consult for). I doubt if this doctor would be willing to have me as a ‘frequent-flyer’ but as I’m long-term unemployed, conventional insurance would be ‘beyond outrageous’ given (hypothetical) ‘pre-existing conditions’. The obvious answer is Medicare For Everyone but that ain’t gonna happen…

I go & (hopefully) my catastrophic-care insurance kicks in..

Actually, if you go to the ER with chest pains I think you are hoping not to have to collect on your catastrophic care policy.

I’ll gladly pay if they find out it was a strained chest muscle.

Is there anything in these deals to prevent physicians from dropping the patients that become expensive and only serving the ones that are cheap? It seems like another model that is designed to prevent risk pooling.

Well, as I understand it, the monthly payment doesn’t get you the actual healthcare, just more convenient access to the healthcare your insurance is paying for. I suppose somebody might get dropped from the plan for calling the doctor at 2AM every time his stomach rumbles, but any actual provision of healthcare is being paid for, and thus isn’t a net cost.

My $49/month payment covers all office visits & office-administered medications & supplies.

Some aspects of concierge medicine - with benefits to both patients and doctors - can already be found within the insured healthcare system. “Micropractices,” where primary care physicians run with a minimal set-up, are an example at the small scale. Property overhead can be divided among the doctors as if they were renting the space on a daily/hourly basis; often reception is dispensed with altogether with scheduling done only online and insurance claims outsourced. I could conceive of a model where patients pay up front and get reimbursed from insurance on their own, further reducing the burden on the doctors.

At the larger scale is something like Kaiser Permanente, which consolidates all health care under one roof: one insurance company, one website, with self-branded hospitals, clinics, and pharmacies. The benefits to the doctors aren’t quite as apparent here (though presumably they can spend less time on office management than those in a small practice), and it isn’t a luxury service for the patient, but it is a more guided process. Patients don’t necessarily have access to more care, but they are more likely to use it when everything from routine physicals to specialist care to prescription medication can all be scheduled/accessed online.

Here in Canada the concierge doctor would be considered a violation of equal care for all and a slippery slope to a “two-tiered” system. What often goes unmentioned is that many employers already offer “supplemental” insurance which confers perks like free ambulance services and the ability to have private rooms during hospital stays.

Does anyone have the math on the tipping point between extra costs for additional preventative services and long-term savings due to better health outcomes? There seems to be much discussion about the costs of being uninsured vs. insured, but I’m not sure if there is much about insured vs. more insured - or if the outcomes are any different.

There’s also the possibility that even if concierge services (or drastically increased access to preventative medicine) was made available to all, it’d still be the wealthier set that took the most advantage of these additional services…

A lot of the above assumes (without any evidence) that it is hard to get in to see the Doc if you are a mere (not paying extra) patient.

IMHO, not so. When I need to see a Doc I am able to get in very quickly, same or next day if need be. And, I am not rushed or pushed through the system. The Docs I see take enough time to deal with any issues I may have. And, Medicare is paying the bill, but, not paying any extra.

By the way, I don’t have any problem talking to various Docs on the phone. They may not be instantly available (may be in surgery or with another patient) but the call back is quick. The assumption that there is or will be a Doc shortage is dubious at best. It does, however, play well with those who are sure Obamacare can’t/won’t work.

When I need a doc, I can see one in under an hour, at “convenient care”. Unfortunately, my new, inferior, Obamacare compliant insurance dings me if I use convenient care instead of my family physician, who I rather conspicuously can NOT see on an hour’s notice. But I could, if I signed up for this sort of plan.

Well, then consider that your insurance company has just raised your rates by $49/month, and go see whom you want to. Why do you have new, inferior insurance in the first place?

“Why do you have new, inferior insurance in the first place?”

Because Obamacare made my old plan illegal, that’s why. Thought I was (“Obamacare compliant”) clear about that.

[...] Source: https://thesamefacts.com/2013/01/uncategorized/concierge-medicine-an-answer-to-the-crisis-in-primary… [...]

There are different “concierge” models, some of which stress a kind of exclusivity, and others that stress expanded services and faster access. Neither is optimal for health care, but at the same time, many doctors remain “open” to non-concierge patients, they just limit the number.

I don’t think that concierge medicine can be discussed in a vacuum or without context, and the context is, for the last 25 years, Medicare, and private payers in parallel, have adopted a physician reimbursement model that grossly undervalues physicians whose main role is to use judgment in evaluating what patients need, and to grossly overvalue physicians who “do stuff” even if that stuff is blindingly unnecessary or even bad for patients. This has had the effect, among others, of significantly accentuating the reimbursement difference between specialists who do stuff and PCPs and specialists who don’t do stuff (rheumatologists and neurologists and non-interventional cardiologists are experiencing a similar fate). With this reimbursement differential comes career selection preference that has resulted in a looming shortage of PCPs. There are other reasons for this dynamic, for one, the desire for doctors to be less personally invested in their practice and their patients, and thus, not to work so hard. I hesitate to say that, but it’s achingly true. I had a complex test a few days ago and the radiologist stayed in the next room the entire time and did not even say hello. I interacted completely with the tech.

You also have the rise of the uberneedy patient whose management needs (especially with respect to medication management) dwarf anything PCPs dealt with a generation ago, such that not only do PCPs get paid LESS for these patients (very often, Medicare beneficiaries) but they require an inordinate investment of time.

I anticipate that the ACA will have the result of making Medicare beneficiaries even less desirable as patients.

There are many possible answers but the first and most obvious is to completely reboot physician reimbursement at the Medicare level to realign these incentives, and pay doctors for their judgment and not their ability to order more and more.

Again, we have the unsupported assumption that, somehow, Medicare insured patients are having trouble getting in to see Docs.

Just isn’t so, at least in my very high cost S Cal area.

In fact, the billing folks at several Docs in my area (and several Docs) have told me that Medicare is better than private insurance because it pays promptly and without the usual trying to avoid payment baloney so common with private insurance.

Southern California is its own world — that is, its market conditions are actually very different from other parts of California and most of the rest of the country. In a lot of ways, California, especially Southern California, has internalized practices that doctors in the rest of the country revolted against. Partly this is because Kaiser is so strong in So Cal.

Anyway, it’s a market by market issue of what actually happens to people in various circumstances, so there is no general proposition. For instance, where I live, it is very difficult to find a new PCP. My husband was unable to find a PCP unless he signed up with a concierge practice. Mine was not accepting any new patients at the time.

In addition, the RBRVS is terrible for all kinds of reasons, not just PCP shortage. It is one of the main reasons why Medicare is as financially precarious as it is.

I also notice that the original post did not once use those initials: RBRVS

I don’t even see how you can hope to talk about physician supply and reimbursement without analyzing RBRVS.

Barbara,

I just don’t buy the S Cal is different claim. S Cal, in many ways, is really just a warm Mid-West. (insert smiley face here).

If Kaiser is what makes things different-then why isn’t N Cal (where Kaiser was founded and where it has very substantial market share, more than S Cal) in the same boat? Not to mention Georgia, D.C., Maryland, Virginia and the other states where Kaiser is big. And, why would Kaiser have any effect on Docs who have their own practices and never go near a Kaiser facility?

What I hear from primary care Docs around here is that there is a shortage of private paying patients (apparently the HMOs pay less than Medicare and take their sweet time about it) and Medicare pays the bills quickly. So Medicare patients are wanted-certainly my experience.

My friends and relatives across the country report much the same-no problems getting good care with Medicare.

You can buy it or not. In nearly every other market in the country, Medicare fees are lower (sometimes MUCH lower) than commercial provider payments. The reverse is typically true in So. Cal. (as well as in some other California markets). Yes, indeed, it would be interesting to study exactly why, but it has been the case at least recently.

RBRVS?

resource based relative value scale. It’s how physicians have been paid by Medicare since the late 80s. It is the source of a lot of perverse incentives and their unfortunate consequences in our health care system.

Thank you.

I wish we could distinguish about the quality of the doctors, something that a newly sick person probably is not an expert on and is not able to really make a decision like “I’ll take the one with the 5% death rate because he is cheaper than the one with the 1% death rate” from other aspects of customer care with which we have more experience.

Waiting time is an obvious one. My personal desire from way to much experience is for really comfy chairs (ideally recliners) in the waiting room. I am really serious about this; sick people and their care givers spend lots of time in waiting rooms. It should be possible to nap. I would certainly pay for that.

In India, doctors and hospitals offer lower payment rates to people willing to come at odd hours, like 5:00 am.

Great comments. Interesting to hear about different experiences and in different areas of the country. I do apologize for not defining ‘concierge medicine’ but thank you for doing so. The comments suggest the topic itself is a great microcosm of the larger debates in the health care system and that the issue is non trivial in terms of thinking about those issues. Barbara, thank you for raising the Resource-Based Relative Value Scale (RBRVS) in relation to primary-specialty care incomes and fees. I am exploring the implementation of RBRVS and I found your comments perceptive. A major question is how to appropriately weight different kinds of physician work. It’s a fascinating and perplexing issue both in terms of what the best approach is, and how it was developed and implemented.

From a UK perspective this is an interesting discussion from what appears to be an alternative universe. Goodness knows the NHS has its problems but “concierge medicine” (should that be concierge primary practice) with “general practitioners” being paid essentially on a per-capita basis is so deeply embedded that most people here cannot imagine any alternative. Whenever I want to see a doctor I just make an appointment and go and it’s all paid for out of general taxation. I can even just turn up and will probably be seen with a bit of a wait. There are what are referred to in this thread as “frequent flyers” but they are handled without crippling the system.