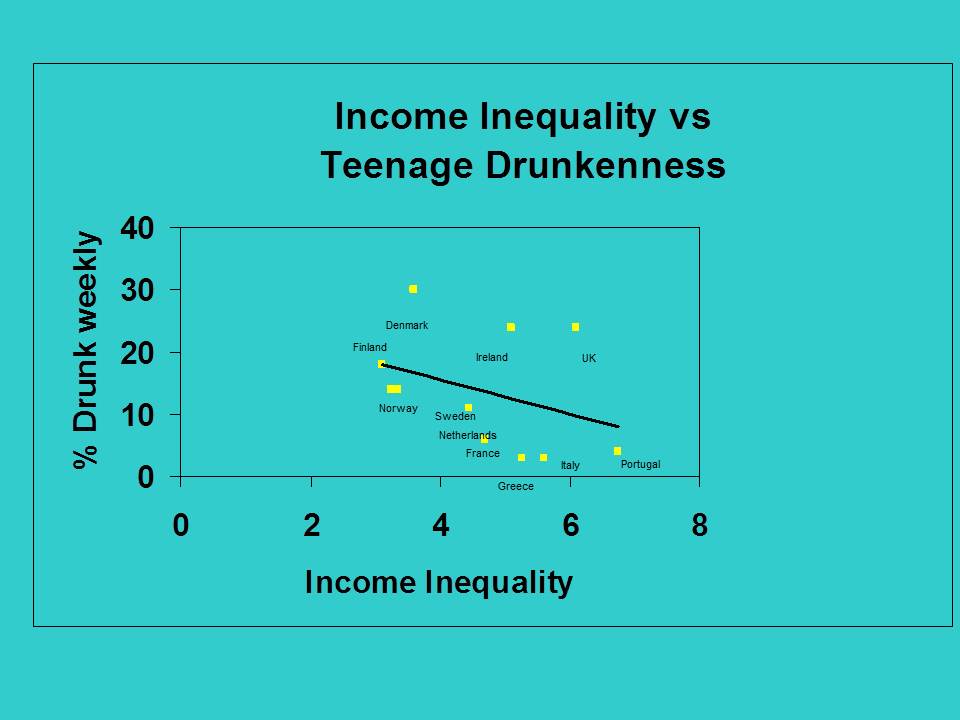

The Spirit Level was a widely-read book that argued that societies which are more equal in terms of income are physically healthier (e.g., had lower rates of infant mortality and psychiatric disorder). Two experts in alcohol studies, Doug Cameron and the late Ron McKechnie, throw a spanner into the works of this hypothesis in the latest issue of New Directions in the Study of Alcohol. In general, alcohol problems tend to be more rather than less prevalent in more economically equal societies. The slide below shows the relationship for teenage drunkenness, and parallels the result for other alcohol problem indicators.

The Spirit Level is one of many examples where academic leftists advocate for a values-laden public policy position (in this case, policies that redistribute wealth downward) as if it were merely the logical implication of unassailable scientific facts. A problem with this strategy, beyond its dishonesty, is noted by Doug in his paper:

If you are going to make a case for a more equal society, and you write a book about it, and you use numbers to make your case, then you are putting your case under scientific as well as moral scrutiny. You will be judged on your numbers as well as on your political beliefs.

But Doug (like Ron a socialist, BTW), understanding the difference between scientific facts and political values, also says:

I actually like the Spirit Level ideology. I approve of the idea that we should live in a more equal society.

I wish more academics on the left followed Doug and Ron’s example of making their value commitments explicit and unapologetically defending them as such instead of hiding behind Excel charts. Why has it become hard for so many leftists to say out loud that they care about the poor because it’s the morally right thing to do, not because “the latest regression model suggests that maximization of well-being among lower-income population strata may yield gains in health indicators…but more research is needed”?

Because they’re afraid of winning.

I’d like to see more of that article than just the graph above before buying such a hypothesis. Not only are these awfully few data points, levels of teen drunkenness seem to be more strongly correlated with geographical and culturally similar areas than with income inequality. You’ve got the British Isles and Scandinavia at the top, and Mediterranean countries at the bottom.

I wouldn’t consider it impossible that increased income equality has negative side effects, but I’d like to see that claim supported a bit more thoroughly. I presume that the article has more and also provides a causal connection instead of just observing a statistical correlation?

With respect to your observation about values, my personal pet peeve is actually the term “income inequality” itself [1]. I don’t really care much about how rich Warren Buffet or Bill Gates have struck it; what concerns me is the poverty that millions of people in the United States live in (and let’s not talk about other areas of the world). And often, when people talk about income inequality, poverty seems to be really what they mean. But whether the word “poverty” sounds too socialist or that implying that there could be poverty and suffering in America is treasonous or that there’s an unspoken assumption that people who are poor brought it upon themselves, “poverty” is not used very much even when it is the most accurate descriptor for a problem.

(And yes, poverty is a hot-button issue for me. I really don’t like being the member of a society that prefers to pay its taxes in human misery rather than in dollars.)

[1] Outside of a scientific context such as the aforementioned paper that actually is about income inequality metrics and does not use the term as code.

The reason “poverty” is used less than “inequality”, is that we’re defining “poverty” on a relative basis. If you define it on an absolute basis, it’s been declining in the US for decades, and is by now quite rare.

If you’re going to define “poverty” on a relative basis, you might as well just cut to the chase, and talk about inequality openly, because you’re just calling inequality “poverty”.

Seriously, I’ve been to places, like the Philippines, where there really is poverty. We don’t have poverty here. Not to any great extent. We just have people who aren’t as well off as other people. The world is interconnected enough for people to notice this, and scoff at discussions of poverty in America.

False, there are millions of Americans who have trouble affording the basic necessities of life, including food. Even beyond that, there’s a level of poverty where you’re not literally starving, but are denied basic human dignity; this is, as RFK put it, “the breaking of a man’s spirit”. That you may not personally know such people does not mean that they do not exist.

America has actually one of the highest absolute poverty rates in the developed world, especially when it comes to child poverty.

That the situation in Sub-Saharan Africa is even worse is no excuse to not keep our own house in order.

By the way, I am fully aware of the situation elsewhere in the world (which I explicitly mentioned). I was an active member of amnesty international in college, and human rights issues are often intricately tied to poverty. In many ways, poverty is a human rights issue all by itself.

While I do believe that we have real poverty in America, I do find it hard to understand how anyone who has a home with working cooking facilities can be unable to buy food. I recently bought dried black-eyed peas for $2/pound in the San Francisco Bay Area. A pound will probably provide me 8-12 servings, if not more. Sure, you may not be able to buy the food you like, and if you don’t have cooking facilities or can’t reach a food store, that’s more problematic, but otherwise, the coins in your couch cushions should buy enough wholesome rice and beans to fend off starvation. And if you can’t, food stamps provide $3-5/day per person. I’d have trouble eating that much rice and beans.

It’s a serious problem, (And routinely dismissed as “blaming the victim”.) that the poor generally are not economically savvy. A big part of why they’re poor! The people most in need of basic home economics are least equipped with it.

While putting together a really cheap and nutritious diet is not all that difficult, most of the people who’d know how to do it wouldn’t be poor. This is not, apparently, not one of those life skills that the schools are effective at teaching. You mostly pick it up from your parents. If they don’t have it to pass on to you, bingo! Self perpetuating poverty. Poverty isn’t just a state, it’s a culture, too.

By a curious coincidence, there’s a bowl of dried black beans soaking on my kitchen counter right this instant. It has a date with the crock pot. Yum!

No, Brett. You’ve been to places where poverty is out in the open for all to see, like the Philippines.

You don’t see poverty in the U.S. because you don’t go to the right places. If you want to see poverty, come to New Mexico and visit a border colonia. If you want to see poverty, go downtown in any sizable city and visit a rescue mission. Check under a bridge abutment. We hide it pretty well here. That doesn’t mean it is nonexistent.

No, I don’t think you understand: Some of those people have cellphones, therefore, US poverty doesn’t exist. QED.

Hell, a lot of the poor people in the Philippines have cell phones. They’re not inherently expensive, you know, it’s just that the way we buy phone service here in the US is really screwed up.

I’m sure there’s *some* real poverty, I mean poverty by 3rd world standards, in the US. We’ve got over 300 million people here, after all! Doesn’t change the fact that most of the people we call “poor” today in America would not be considered so by the standards used to determine poverty several decades ago. They’ve got roofs over their heads, can afford enough calories, and if the schools had actually taught them nutrition, could be eating healthy diets.

If you judge poverty by absolute standards, it’s been declining for decades. If you judge it by relative standards, you ought to be honest, and call it “inequality”. That’s my point.

The two theses - that inequality leads to worse health outcomes and that inequality leads to less alcohol abuse - aren’t mutually exclusive. Leaving that aside, why do you regard the latter thesis as better-supported by evidence?

The slope of the regression line and the distribution of the data points tells me this isn’t a very robust effect. Did Cameron and McKechnie report an R-squared? It can’t be very big.

Yes!

Some questions:

Are Ireland and the UK really more “socialist” than Italy and Portugal in the past 20 years? I don’t think so. Also, isn’t this graph sort of like saying the suicide rate will go up if we have Swedish socialism?

Finally, what is, after all, “teenage drunkenness”? Is it alcoholism? Is it having a party because people are having fun (I say this as a non-alcoholic drinker, by the way)? Is there any consequence like a higher incidence of drunk drivers who kill pedestrians or other drivers? Oh wait. Lots of those nations have mass transit. Hmmm….

Something tells me I’ll still look to the Danish and other geographically located societies in terms of public policies to pursue…

I would also like to see a comparison of the “low inequality” countries that assesses how they achieve that status — is it a compressed income scale (Japan, historically), or low unemployment, or large transfer payments/income supports for the unemployed? England had, for many years, a large proportion of its population receiving public assistance and, at the same time, a massive and growing alcohol problem. Japan, during the same period, had low unemployment and much less severe alcohol issues. My bias is that full employment and/or a compressed income scale is a better indicator of social health than income supports/public aid, because giving up on creating jobs for all or most is in itself a sign of social inadequacy.

I think it’s tricky to judge at what point it’s appropriate to inject moral insight into a policy problem. I thought of Professor Humphreys’ post when I read this quote from an article on the Spain bailout in the NY Times.

See how this (presumably liberal) professor deploys a moral argument, arguing that banks and insurance companies are shirking their responsibility for Spain’s plight. I’d argue that the imperative in this situation is to pursue policies that stabilize the Euro and improve the economy, regardless of whether banks and insurance companies are made to suffer for their errors.

Keynes had the right take on this when he referred to “magneto trouble.” Martin Wolf, back in 2008, came down on the side of removing moral arguments from the discussion about the economy (registration required):

I’m not sure this is exactly a moral argument. It’s more of a contract-law/equities argument, seems to me. If I buy do something that puts me at risk of a huge loss, and someone else who is also at risk does something to mitigate the loss, I’m a free rider if I don’t contribute. And although that problem is typical called “moral hazard”, it’s not moral in the usual sense, but rather about the efficient functioning of markets.

I disagree. Spain has worked out the contract law/equities aspect of it by taking responsibility for payment being made to the lenders. My point is that whether or not this is a morally appropriate solution is less important than whether it’s an effective solution. (Or, to frame this in a way that’s more congenial to Prof. Humphreys’ thesis, the most important moral issue at stake is the utility of a solution to the Spanish and European peoples.)

There’s a similar moral narrative about Greece, though it comes from the conservative side of the aisle. In that narrative, the Greeks spent and borrowed too much and collected too little in taxes. They deserve what they are getting, and ought to be made to live up to their agreements. As with the liberal narrative about Spain, I’d propose that this circumvents the question to which I’d give priority: What policy choice will cause the least pain and most benefits throughout the Eurozone?

And that’s where the discussion of moral hazard comes in. Would massive financial aid to Greece - the ideal liberal solution - encourage Greece to continue to be profligate and ignore the structural problems that led to the current crisis? As you note, that’s not a moral question, but a question about proper functioning of markets. One might resolve the moral hazard issue and the moral issue the same way - say, by denying any relief to Greece - but they are different issues.

I’m not sure what you’re disagreeing with. Spain has (under coercion) dealt with the contract law problem by assuming debts it had no legal obligation to assume. One can make a purely market-based argument that allowing well-connected central-EU banks to cover their abject failures of due diligence by exercising a Rajoy Put is both stupid and counterproductive. I think that you’re taking the language in the piece you quote as being about morality when it’s perfectly plausible to read it as being about contracts and market efficiency/effetiveness.

So much depends on where you draw the edges of your frame. We could tell a very similar moral-hazard story (or morality tale, for that matter) about Greece, but with the added recognition that for every seller of a dodgy debt instrument there is a buyer. If Greece’s structural problems are so well known, what have people been doing buying their bonds for the past decade-plus, other than imagining they could pass the bomb to the next sucker before it blew up? And neither morality nor efficient market rules sanction that kind of behavior. (Yes, Greece also has a structural deficit at this point, but it’s one that was hugely exacerbated by greedy idiots in search of a profit they could privatize, while socializing the inevitable losses.)

A question that nags in all such studies is: How was the data collected?

If you ask a teen if he/she drinks, smokes pot, has sex, etc. will they tell the truth? If they do engage in risky and/or illegal behavior they have good reason to deny it. If they don’t engage in such behavior they may say they do to seem cool or to shock. Such motives could easily skew result by 10 or 20%.

If the study relies on reports from law enforcement things could get even more complicated.

It is fashionable to worry over teen drinking but in my teen years I recall everybody drinking and getting high in general and most of us survived with minor damage to our bodies and souls. No doubt many people who wring their hands over the wasting of youngsters lives on sin and debauchery did some of that sinnin’ in their turn.

So what was this about? Oh yeah, income equality! I’ll take some of that and the problems it may engender.

I’m not sure if this really “throws a spanner into the works of this hypothesis.” Teenage drunkenness doesn’t exactly equal physically unhealthy. When we’re talking about 20 percent drunk weekly, we’re not really looking at actual health problems. There also seems to be not quite enough data to really make the point stick. How about Russia, the U.S., India, Argentina?

@All who raise methodological issues. First, this is an example slide, the same relationship holds for population heavy consumption, adult drunkenness etc. As for other methodological criticisms, I would go further than what has been posted — after all correlation does not equal causation, aggregating to the national level hides lower-level differences, among other things. But, and this is a huge point: This analysis is EXACTLY (not similar, exactly) the same sort of analysis that underpins the Spirit Level. So if you say “I don’t believe the analyses because I know that inequality causes X health problem”, remember that what you “know” rests on exactly the same methods as what you consider unbelievable.

For me personally, this is not a problem. My commitment to the poor does not rest on anything so fragile as a correlation or a Beta weight, but YMMV depending on whether you believe certain things are morally just per se or see them as only as implications of scientific findings that could change tomorrow.

It is my impression that far northern societies have always had alcohol problems greater than average. Especially in winter. I haven’t studied the issue, but that is the impression I have long had. Russia, where income disparity is rather extreme, is famously cited as having alcohol problems (except on this graph where it is, perhaps conveniently, absent).

The list above includes far northern societies and then relatively far north (Ireland and UK) as the most alcohol abusive and Mediterranean societies as least so. In fact the graph could suggest that alcohol abuse is a function of latitude.

But bashing progressives is such fun.

Per Gus above, more countries to add, such as the former USSR, Latin America, Australia, East Asia, and North America would be welcome and more instructive than the handful above…

Good point Gus about Russia…

I agree of course — and this same point would undermine every conclusion in the Spirit Level equally or more. The Spirit Level also excludes the many countries with widespread equality and poverty (i.e., everyone is in dire straits), all of which have poor population health indicators.

Count me in for the latitude hypothesis. Dividing countries into North/South and high/low teen binging could easily yield a correlation of 1.00.

Maybe Doug and Ron’s superior values got in the way of seeing the obvious.

@calling all toasters. Well spotted. Your argument essentially is that inequality is not the only or even primary cause of poor health indicators. Makes good sense and applies to whole Spirit Level book approach.

Nice try at intentionally misunderstanding me, Keith.

1) Who said that teenage binging is an important health indicator? How about infant mortality, life expectancy, sickness rates? Those at least are outcomes. It seems kind of obvious that this was cherry-picking by Doug and Ron, only it doesn’t work.

2) If you did the same chart with malaria in Asia, you could probably find some correlation with inequality. Guess what? Inequality may be a cause, but it’s not the primary one. It’s fairly well-defined by geography. If a bad scientist wanted to make a graph “showing” that more/less inequality leads to more malaria, they could do it.

3) My argument, contrary to your speculation, is that grown-up scientists consider all relevant co-variables before they go ahead and publish a simple correlation.

@calling all toasters:

Who said that teenage binging is an important health indicator? How about infant mortality, life expectancy, sickness rates? Those at least are outcomes.

Agreed. Spirit Level should have considered this, but didn’t.

If you did the same chart with malaria in Asia, you could probably find some correlation with inequality. Guess what? Inequality may be a cause, but it’s not the primary one. It’s fairly well-defined by geography. If a bad scientist wanted to make a graph “showing” that more/less inequality leads to more malaria, they could do it.

Agreed. Spirit Level should have considered this, but didn’t.

grown-up scientists consider all relevant co-variables before they go ahead and publish a simple correlation.

Agreed. Spirit Level didn’t do this, and it should have.

Great points across the board, no arguments from me.

If you say so. I have no particular interest in Spirit Level one way or the other, other than a general belief that societies with a large middle class tend to do better in most of the important social outcomes. My subject was, and is, the ridiculous rebuttal to it seen in your post. Your rhetorical jiu-jitsu doesn’t really distract me from that.

There is no rebuttal at all offered here values wise, quite the reverse. Science wise yes, for the reasons for which you yourself so well argued.

The “science” that you *approvingly* cite in your post (i.e. Doug and Ron’s)is incredibly bad. Now you have taken my argument that they have produced bad science and transferred it to Spirit Level, because the authors of that book have (allegedly) committed the same errors. I have not read that book, or any other criticisms of it, and have no way to critically appraise it. But you have the temerity to strongly imply that I back you up in disapproving of it. I don’t.

On second thought, I think what we’re arguing about depends on the emotional tone of your post. If I read the binging research as being a parody of the techniques Spirit Level, then we actually have no disagreement. But I certainly read your post as being supportive of that (i.e. Doug and Ron’s) work as a rebuttal to the content of the results of that book, and I didn’t think that familiarity wiht the book’s techniques was assumed.

Any study of alcohol abuse that doesn’t control for latitude will produce nonsense. Egalitarian Sweden and inegalitarian Russia both have lots of heavy drinking because they have long winter nights.

Dear Keith,

Do I understand correctly that you are saying that you are saying Wilkinson and Pickett were dishonest? Do you say their conclusion are not valid?

If so I’d like to learn more about what is wrong with their method, data, and/or conclusions. Because I don’t understand.