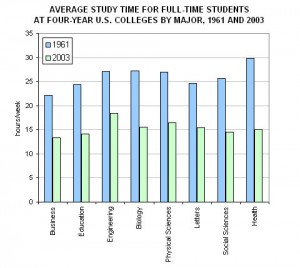

This NY Times Blog reports some interesting facts. How do we explain the decline in study time? Perhaps the new generation of students is (!) smarter and has a higher productivity per minute of studying? Or, do professors now hand out less homework? These averages may mask a composition shift. As the number of undergraduate slots has increased over time, the marginal college student may be less hard working? Or, is this evidence that the new generation is soft and simply seeking the good life.

IMHO, it may be evidence that students rarely tell the truth when asked about their study time (and may not even know how much study time they put in and so may not be able to accurately answer questions about study time). Gotta wonder if someone who learns Japanese in school puts in less time than, say, someone studying chemical engineering.

This NYT blog is full of questionable assumptions such as engineers make more money due to their majors. While perhaps true for those just out of school the lifetime income figures are likely to be quite different. Most of the engineers I knows believe that they quickly hit the engineer’s income ceiling and the only way to move up in income is to switch to management or some other non-engineering area-or, of course, start their own company.

I wonder what sort of adjustments they made for the dramatically increased productivity of research and other aspects of studying. Internet-based research tools enable me to accomplish in an hour what used to take me a day or more in the library when I went to college in the 1960s. And software tools for data management, data analysis, graphics, and word processing have made the nuts and bolts of studying much more efficient. I’m skeptical of these sorts of comparisons over time because of fundamental shifts in the nature of the activity. An hour spent studying 50 years ago is not exactly the same as an hour spent studying now.

It could also be that today’s students have less time to study because they need to hold down jobs to pay the bills. In fact, the research by Babcock from UCSB cited in the NYT posting shows exactly that: hours spent working doubled between 1961 and 2003.

However, this increase makes up only 50% of the decrease in study time, as it starts from a very low baseline in 1961. My guess would be that there might be a bifurcation based on income: some students work much more outside class, often 20 hours or more, while others simply study less and enjoy more leisure. (I would not be surprised if the engineers who study harder also work more outside, as they tend to come from poorer families.)

Of course, the US is a wealthier country now than 50 years ago. But a much larger percentage of people now go to college, tuition has increased, and student aid has been cut. So many people have to work. Those that don’t enjoy the extra free time.

I agree with TS, and would add that the decrease in study hours per week might also correlate with reduced number of units taken at one time, in order to accommodate one’s need to work for a living.

Working more hours for pay usually means a person needs to take fewer classes per semester, and more semesters per degree, in addition to reducing the number of hours per week available to study.

That said, I would also note that, using biology as the subject, college text books from the 1960s were written at a significantly higher reading level, contain far more information-dense illustrations, and require greater concentration to understand. Although I attended in the 1990s, I often sought out the older texts for background in classical topics in biology because they were so superior to today’s offerings (that appear to be written by committee, and illustrated by graphic artists more interested in visual appeal than in content).

However, I was in school as an older student, primarily to satisfy my love of the subject matter, and thus was not representative of most biology students, the majority of whom seemed quite content to settle for C’s in return for their minimal investment of time. I was very surprised at the apparent lack of interest in the subject, even among bio majors. Eye-opening.

The rate of college attendance for high school graduates has gone up by over 20 percentage points during roughly this time span, from 45.1% in 1960 to 65.6% in 1998. While I’m sure that many industrious students simply didn’t have access to college in the early ’60s, I imagine that the much higher rates of college attendance today also involve a greater number of relatively un-serious students who bring down the study time averages.

There are probably many explanations-the need for time to work, technology-driven increases in efficiency. But then there is something like this.

Let’s say I am a biology professor at a major research institution. It’s pretty clear to me that my main function is to get grants and focus on research productivity. I teach, like, one class per year, but there are 250 students in it. I have to submit a grant proposal in June1, which means that the thing has to be written well before that, so the three manuscripts sitting on my desk need to be wrapped up and submitted. So I give my lectures straight out of Alberts (The Molecular Biology of the Cell), because it is so comprehensive and the illustrations are so professional, so it is pretty easy to put together a good Power Point lecture. I’ll give three exams and a final, but the questions have to be easy enough to that my grad student TA’s can grade the exam with the key that I make up. Also, we curve to a B.

So the average (ya know, B) student can come to class much of the time, maybe even like 50-60% of the time. Pretty soon they catch on that if they just get the handout and read the chapter of Alberts from which my lecture was derived, they can get an average (ya know, B) grade on on of my TA-graded exam.

It’s not that I am not working. I am working my a** off, and going kind of nuts because in the midst of all of this stuff that I am supposed to do, I also have to teach this class of 250. I’m not giving them homework. They just need to study for the three exams and the final.

And, since I am an assistant professor (who else would have to teach a class like this), I know that as long as I don’t show up drunk and naked, my teaching is not going to determine whether or not I get tenure. BUt this grant that I am submitting in June? THAT is going to determine whether or not I get tenure.

So, let’s say, I get my grant, and I sail through tenure. I get a sabbatical. Who will teach Cell Bio? Well, not any tenured people. Not any of the assistant professors-they are busy teaching their won 250-student classes. So, let’s hire an adjunct for, like, $5000 for this class. Now this person who is teaching this class for $5000 clearly has other things to do so that they can make enough money to eat. Perhaps they are teaching four other classes like this. One a one-year basis. So I give him/her my notes, but you know, they still want to do a good job, so they put some time into reworking the lectures. Oh yeah, and they don’t get TA’s, so they are doing all the grading. So it’s multiple choice exams. Again, this person is knocking themselves out, for maybe $20,000 and no contract, but this does not make for a terribly challenging class.

See what I mean?

“I know that as long as I don’t show up drunk and naked, my teaching is not going to determine whether or not I get tenure.”

The head of my old Oxford College, Corpus Christi, can only be fired (unless they’ve changed the statutes since I was there in the Palaeolithic) for “gross and persistent immorality”. (My italics.) So one drunk naked lecture isn’t enough.

Harold Macmillan said he liked being Chancellor of Oxford University (a purely ceremonial office) because it was the only post from which he could not be removed for any reason whatever.

The decline from ’61 to ’03 is mostly a composition effect: the student population today is nothing like the student population then. The variation between majors, on the other hand, defies easy (dismissive) explanation.

Could it be that students treat school as a licensing regime, and go through the motions in order to get a job?

My SO is a grad student, and she has taken some classes at a state school to jump through various hoops. Her reports on psychology students indicate to me that the bulk of people doing the program are there to get a cred that lets them work a middle-class job. It is like going to the DMV, but takes longer and costs more.

If that is the norm for non-elite students, why would we be surprised that students are studying less?

Get ‘er done.

A gentleman’s C is okay for me.

Didn’t they require all students to waste time learning useless subjects like Latin in the 60s?

“How do we explain the decline in study time? ”

If only there were an academic discipline that specialized in answering such questions through both observing students and talking to them. We might call it, I don’t know, Anthropology, or maybe Sociology.

But, sadly, in the real world we are doomed to sit on our asses, spouting theories based purely on our pre-existing opinions and devoid of any empirical content… After all, that IS the economics way…

Let me add a further point. Once again here we see the sheer stupidity of collapsing distributions to single summary statistics and expecting something useful from this procedure. In this particular case there is the obvious point that a much higher fraction of the population is going to college today than in 1961.

Hypothesis: some fraction (10%?) of the US population is willing to work hard (let’s say 27hrs a week) on college. That was true in 1961 and is just as true today. That fraction went to college, with very few other people joining them.

Fast forward to 2011, and we have that 10% of the population joined by another 20% who are rather less willing to put in those hours…

A simple plot of the distributions involved could provide vastly more insight into this matter than all this pontificating.

I’m not sure “willing to put in those hours” tells the whole story. My point was that as faculty time and effort are pushed away from teaching, perhaps courses require less time for student success. Add to that grade inflation. I certainly think that the expansion of the college population is also a factor-ability may have been distributed over a narrower range, toward the top, back in 1961. However, it is not necessarily the case that this expanded population is not “willing to put in those hours” to the same extent as, say the guys that Erich Segal (yes, I read a lot of bad fiction in my teens) based his characters on.

So it would be interesting to look at what today’s students are doing with their “extra time”. Are they working for pay? Many of them are. Are they taking a reduced course load and taking longer to graduate? Many of them are. Are they spending more time on Facebook? Many of them are, but if they can study 10 hours a week and still get a 3.5, well, whose fault is that?

And the faculty and administrators are also “willing to put in the time”, its just that so little of what they do actually has to do with anything that translates into increasing the amount of time that students have to “put in those hours”.

A number of the explanations here are interesting, and might perhaps be useful in some other context, but Brock is on the right track. The real explanation has to do with what Babcock defines as “studying.” It’s all schoolwork.

The computer (and perhaps more specifically the Internet) alone can explain virtually of this. Consider the amount of time it took to write and research a term paper in 1961. It takes undergraduate students a lot less time now. That’s not because students are lazier; that’s just because it’s actually much faster to find and verify information.

Never mind how much easier it is just to type the paper.