Edward Hopper’s paintings have a special emotional resonance for me. They capture moods and people and scenes that remind of the time in my life when I lived in a declining industrial city in the Midwest. I worked on a night shift, and with my body clock flipped from almost everyone else’s, I was awake and about when the city was empty, dark, lonely and yet also peaceful. I saw the other world of the city, the one populated by the night people who come out when the the day people are asleep. Hopper always brings me back to that experience in a powerful way.

I was therefore glad to receive as a Christmas gift this year a book about his art, which included many excellent paintings which were unfamiliar to me. But the text of the book reminded me how much I detest most art criticism. Apparently, Hopper was exploring the tension between being and becoming in a world in which the primordial angst in humanity’s soul struggles against the bleak weltanschaung of modernity, perennially in tension with a Rousseausque subversion of the tropes of quotidian existence. Or something like that.

Perhaps I am too “low church”, but when I read art critics, I usually think three things:

1) I have doctoral level education, and I can barely understand what you are saying

2) I suspect that you are writing more about yourself than the artist in question

3) You are making it harder rather than easier for people to get something out of the experience of art

Many people are intimidated by art and thus shy away from it. Jargon laden art criticism makes this problem more rather than less acute, and that makes me mad both on my own behalf and on behalf of other people who miss out on the richness of art because high-end criticism makes it seem over their head. In contrast, although it probably gets derided as mere “art appreciation class” instead of serious criticism, I am quite grateful when an expert relates plain-spoken observations about a painting that help me understand it better. Something as simple as “Did you ever notice that there are no cars in Hopper’s street scenes and that makes the cities look even more empty?” or “He painted this just after a big exhibition at which he saw for the first time some new styles that he wanted to try himself” have helped me see new things in Hopper’s work.

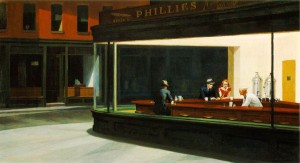

There was a nun on public television some years ago who did just this sort of thing. I literally saw 10 minutes of her series by chance when I was sitting in a hotel lobby, but it was the kind of commentary for which I was grateful, and it focused on a great Hopper painting, Nighthawks (which I have a copy of hanging in my office today). Her name is Sister Wendy and I was fortunate to just now find on line her take on this painting:

Apparently, there was a period when every college dormitory in the country had on its walls a poster of Hopper’s Nighthawks; it had become an icon. It is easy to understand its appeal. This is not just an image of big-city loneliness, but of existential loneliness: the sense that we have (perhaps overwhelmingly in late adolescence) of being on our own in the human condition. When we look at that dark New York street, we would expect the fluorescent-lit cafe to be welcoming, but it is not. There is no way to enter it, no door. The extreme brightness means that the people inside are held, exposed and vulnerable. They hunch their shoulders defensively. Hopper did not actually observe them, because he used himself as a model for both the seated men, as if he perceived men in this situation as clones. He modeled the woman, as he did all of his female characters, on his wife Jo. He was a difficult man, and Jo was far more emotionally involved with him than he with her; one of her methods of keeping him with her was to insist that only she would be his model.

“From Jo’s diaries we learn that Hopper described this work as a painting of “three characters.” The man behind the counter, though imprisoned in the triangle, is in fact free. He has a job, a home, he can come and go; he can look at the customers with a half-smile. It is the customers who are the nighthawks. Nighthawks are predators - but are the men there to prey on the woman, or has she come in to prey on the men? To my mind, the man and woman are a couple, as the position of their hands suggests, but they are a couple so lost in misery that they cannot communicate; they have nothing to give each other. I see the nighthawks of the picture not so much as birds of prey, but simply as birds: great winged creatures that should be free in the sky, but instead are shut in, dazed and miserable, with their heads constantly banging against the glass of the world’s callousness. In his Last Poems, A. E. Housman (1859-1936) speaks of being “a stranger and afraid/In a world I never made.” That was what Hopper felt - and what he conveys so bitterly.”

Interesting thoughts, useful information, perceptive observations all communicated in unpretentious and clear language. How I wish more art critics would follow Sister Wendy’s example.

And yet very little of what you’ve quoted touches either on verifiable details of the painting, or on visual tradition and context. Writing about art can be far richer than either that or the kind of catalog filler you rightly complain about at the top of the post. I don’t have specific recommendations for Hopper, I’m afraid. I had remembered Peter Schjeldahl’s recent review of a Hopper show as illuminating, but it seems to me now to differ from Sister W less in kind than in sophistication — he too turns it into a kind of theater interpretation, using data from Hopper’s life to suggest interpretations of the enigmatic figures. For an example how interesting a book on art can be, what a range of knowledge it can bring to bear, check out Michael Baxandall’s Painting and Experience in Fifteenth-Century Italy.

I got yer art criticism right here. “Goodfellas”

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YlyXZG2dupo

I’m going to nominate a (4.) I am writing mostly for the purpose of getting other art critics to respect me and think I am swell, rather than for the purpose of helping novice viewers enrich their experience of the art.

I’m not into traditional visual art (and hence its criticism as well), but if I had to make a charitable case for the critics, it would be this:

We don’t expect particle physicists to construct and describe their theories using only 5th grade English level. That’s because of the complexity and nuance in need of conveyance. And in order to economically communicate those ideas and observations, it requires compacting some of them into jargon mutually accessible among the peers. During the course of formal education, to-be-physicists get the chance to become familiarized with that jargon and idiom. This insularity of expressive power doesn’t bother the laity because engagement with matters of particle physics is effectively restricted to those already inculcated and a penumbra of those enthusiasts self-inclined to make themselves comfortable with the discourse. Art criticism, on the other hand, deals with primary stimuli, purportedly available to all i.e. anyone from the general public can search for an image of a painting on the internet or in a magazine or book or look at the original or facsimile in a museum. This seems to create the expectation that any thread of discourse offshoot from a universally-available stimulus ought to also be appreciable similarly. But it’s entirely possible that those who spend more than a smattering of their time engaging with visual art will have developed, similar to physicists, a jargon and an idiom in order to encapsulate already hashed out themes, motifs and notions. These conversations may in fact be directed primarily at the peer community but the focus brought on by the public accessibility of the primary stimulus as well as its non-utilitarian nature lead to the type of complaints put forward by Prof. Humphreys. The laity not having engaged and followed the thread of art criticism through its development don’t appreciate the jargon-laden prose and feel it is a put-on, but perhaps it’s not.

Daksya: Your remarks completely underestimate the ability of physicists to explain things to a general educated audience — it has been my fortune to spend time talking to a number of Nobel Laureates in physics, and they could all explain what they did and what it meant in plain language. Einstein, Feymann and Hawking have all done this in book-length treatments.

As for your comments on “5th grade English”…if that’s how you view everyone outside of the elite inner circle, you can’t be surprised that some of the great unwashed may be a bit put off.

Your remarks completely underestimate the ability of physicists to explain things to a general educated audience — it has been my fortune to spend time talking to a number of Nobel Laureates in physics, and they could all explain what they did and what it meant in plain language.

You seem to have completely missed the point. I said, “And in order to economically communicate those ideas and observations, it requires compacting…“. Economy is key. This is verbosity: 2+2+2+2+2+2+2, whereas this is a compact version: 2×7, but it requires one more symbol to learn and one more bit of instruction to understand. A physicist given a mandate by the publisher to elucidate the material to a lay audience within the whole expanse of a book, can do so adequately to some degree. In my contrived example, both happen to convey identical meanings, but for sophisticated topics, the simpler prose will convey only a crude approximation or analogy. Penrose thought so as well, hence his insistence on keeping equations in his modern physics overviews. If you read the communications where physicists have to get into the nitty-gritty, such as journal articles 15 pages long, you won’t find descriptions in plain English, which is odd if plain English happens to be perfectly up to the task.

And my choice of 5th grade was just a cursory pick, substitute it with 9th or 12th grade, if you like.

“You seem to have completely missed the point”. One revealing comment after another reflecting a worldview.

In any event, the physicists I mentioned in conversation could explain what they did in a few sentences. Length of time/space available has nothing to do with it. An elitist snob is a elitist snob whether s/he has a minute or a lifetime in which to drone on, whereas a good teacher can convey important things at any opportunity.

Keith, you should understand that academic art criticism isn’t really directed at you. You’re a lay audience: you like Edward Hopper’s paintings because of their direct and figural emotional appeal. You like them because you like them, not because of their placement in a continuum of art-historical development, nor because of the dialogues created with other artworks. Their subject matter speaks to you because it is completely narrative. But what do you think when you look at a Francis Bacon painting, or a De Kooning, or (moving further into abstraction)a Donald Judd sculpture?

Art historians don’t just look at Hopper’s work in isolation, nor do they talk about how his paintings make them “feel.” They see his work in the context of an entire trajectory of between- and post-war American art-and I’d venture that Hopper is in a way the simplest and most straightforward of the famous artists working in that period. He is loved because he is accessible, but he did little to advance the history of art.

My point is that, like everything in life, art history and criticism is a subculture with its own language, subtexts, and side-arguments. When good art historians write, they are not writing for you, an occasional sojourner in the world of art (and incidentally there’s a firm difference between popular art criticism such as you might find in the pages of the New York Times, versus the writing coming out of Columbia University’s art history department, for instance.) Academic art critics are writing for their colleagues, for practicing artists, and in dialogue with the great critics of art such as Clement Greenberg, Donald Judd, Allan Kaprow, Rosalind Krauss, Yves-Alain Bois, Hal Foster and others, who understand their language.

Because of all this, and because I enjoy art and art criticism immensely, it kind of annoys me when social scientists dip their big toe into art history and then pronounce it vapid, with no real or actual understanding of the depth and dialogues involved (Kevin Drum is also frequently guilty of this-I’ve stopped reading him because I can’t stand the shallow way he discusses and dismisses subjects about which he knows nothing.) As Daksya said, would you go to a particle physics conference and, because you don’t understand the lingo, decry the whole enterprise? Art, luckily, can exist on many levels of accessibility: one can like an Edward Hopper painting because its subject speaks to him. Or, going deeper, one can also be transformed by the relational and “subject-less” environmental art of someone like Donald Judd or Olafur Eliasson. I do hate it when I hear casual observers in galleries dismissing all non-figural art, just because they haven’t taken the time to understand it. They wander in five minutes through the contemporary wing of the museum, dismissing great works left and right without understanding, before venturing back into the safety of 19th century figural painting.

But if you want accessible, simple art criticism, read some of Dave Hickey’s stuff. Or Jerry Saltz at the Village Voice. They can take difficult artistic subjects and make them simple. I’d encourage you to broaden your perspective-you have a Ph.D, fine. But in a subject other than art history. Presumably that doctoral level work taught you not to dismiss concepts you don’t yet understand, but rather engage with them.

(All this, however, is not to justify the writing in your Edward Hopper catalogue. It could be awful, for all I know.)

Matt wrote: Keith, you should understand that academic art criticism isn’t really directed at you. You’re a lay audience: you like Edward Hopper’s paintings because of their direct and figural emotional appeal. You like them because you like them, not because of their placement in a continuum of art-historical development, nor because of the dialogues created with other artworks. Their subject matter speaks to you because it is completely narrative. But what do you think when you look at a Francis Bacon painting, or a De Kooning, or (moving further into abstraction)a Donald Judd sculpture?

Matt: I may not have said this clearly, but pointing out connections between one artist and another as well as the historical moment in which the art was created are things I appreciate. Knowing about Gaugin and Van Gogh for instance, their relationship and rivalry, enhances understanding of both. I like receiving that information as I do hearing about emotional elements in a work of art — but there is nothing in that that prevents a person from being understandable.

You are right of course that I do not have a Ph.D. in art history. Hardly anyone does. Can that small community write for each other — of course, why not? What I would ask for is fair advertising, i.e., books would be labeled in the store with “This book is written for Ph.D.s in art history and not for less educated people. If you aren’t in this special group you will not ‘get it’ and should buy something else”.

Keith, I agree that there’s a role for the popularization of art through criticism, in which case the criticism should be clear and understandable. But I’d also argue that artists-and particularly contemporary artists-are often tackling subjects that are probably beyond, or beside, what a casual viewer of art could either tolerate or understand.

Look at a few works by Barnett Newman, for instance. A casual viewer sees basic squares of dark color and says, meh. But if you understand a bit of the context regarding color-field theory, the negation of the figure, and the flattening of space, Barnett Newman becomes much more significant in the history of art. And Clement Greenberg, a fairly difficult art theorist, forever transformed both our acceptance and understanding of this work. Yet most casual viewer has no tolerance for these kinds of discussions and Newman’s work, in their mind, is rendered meaningless.

On an even more conceptual level, look at the work “One and Three Chairs” by Joseph Kosuth. This work engages with language theory, cognitive psychology, the proximity of the subject to the art, and so on. Again, without engaging the deeper meaning and understanding a bit of the theory, the work is meaningless.

The richness of 20th century art (and particularly the abstract line of artists that descends from Marcel Duchamp) is often impossible to understand unless you’re willing to engage with some difficult ideas and, yes, even difficult language.

You would like Simon Schama´s BBC series on a personal selection of great paintings and sculptures. By profession he´s a historian of culture rather than of art, and he tells you things abou the context of the artist and his work that you didn´t know and really help. His Rembrandt book has enjoyable run-ins with the art historians.

In weak defence of the art critics, it has to be said that the artists have led the way since 1850 or so with increasingly incomprehensibel manifestos. Turner was a revolutionary well before the Impressionists, but he just painted - and sold.

When my briliantly talented nephew, Drew Williams was in his first semester of a masters program in sculpture, his first big project was the production of thirty some life size bronze mice.

The sculptures were well recieved by students and professor alike (as usual with his work) until Drew was required to “defend” his work. The prof asked “What do they mean?” Drew replied, “They don’t MEAN anything, they’re mice.”

The professor informed him that in the future he must be prepared to, well you get the idea: Concoct some kind of pseudo intellectual psyco-babble BS.

Drew took the message and walked down the hall and transferred to another department that was interested in teaching real artists how to make real art. He got his degree with honors and is happily continuing his career making wonderful sculptures without a care of what their underlying deeper meaning might be.

I’ll have to disagree with Matt and Daksya.

History is the Queen of the Humanities. And history-apart perhaps from some primary work such as mucking through records-can be highly accessible to an educated audience, in fairly simply language. Why should art criticism be any different?

Nothing, except perhaps some legal work, requires impenetrable language. (And legal work is not impenetrable because it is difficult to understand. It is hard to wring the ambiguity out of straightforward English, so lawyers must perforce draft in tongues.) Even physics can be conveyed in simple English, as the Feynman Lectures show. The Feynman Lectures are almost impossible for a lay person to follow, but that’s not because Feynman used fancy language or jargon. He didn’t. It’s just that physics is a damned sight harder to understand than most other things. I started as a physical scientist and am now doing legal work in financial services. Trust me on this one.

And history–apart perhaps from some primary work such as mucking through records–can be highly accessible to an educated audience, in fairly simply language. Why should art criticism be any different?

History is concerned with the eventuality, sequence and specificity of human actions across time, alongwith any trends and motives as can be plausibly ascribed to these actions. The cognitive module most fit to engage with this matter is social psychology. And most educated humans, who haven’t retreated into their own permanent Walden, will have exercised and honed their own grasp of social psychology just by the continuous daily interactions in their own lives. And in parallel with that development, they will have gotten comfortable with the language used to describe and communicate social psychology. History is a retrospective extension couched more or less in the same language. Visual art deals not just with the superficial reception of vision and the image it describes, but also with the abstractions of the elements and processes involved. This is far removed from base human competence because immediate vision is automatic i.e. I just happen to see the monitor in front of me, without me consciously conjuring the image. Social psychology is however consciously grappled with, and as a deliberate object of conscious cognition. Hence the greater grasp and comfort.

Maybe there is a reason for art criticism aimed at other critics and art historians to be impenetrable to the lay audience. But that doesn’t explain why, so often, the placards that accompany art exhibits in museums, especially the big traveling exhibits certainly aimed at the general public, often suffer from the same flaws.

And let’s not forget that art, unlike physics, is at least nominally meant for the general public. Fine, write articles for other critics; but also, please, write explanations that I and others can grasp.

Anomalous, I don’t quite believe your story. I’d be curious to hear what the professor actually said, versus you and your nephew’s interpretation and repeating of what he/she said. Very good contemporary artists (let’s say Damien Hirst, Matthew Barney, et al.) rarely “concoct some kind of pseudo intellectual psyco-babble BS” to explain their work. If it’s good, people will see its value. And sometimes a great critic, let’s say Rosalind Krauss, is able to reinterpret that work in ways that even the artists may not have recognized. But I’d venture that most people reading Rosalind Krauss straight out of the box, without context, would call her writing “pseudo-intellectual babble.”

And Ebenezer, I think you miss my point. There is a place for straightforward, accessible criticism and art. However….much art and criticism is also not fully accessible to a lay audience. Which is as it should be. Much art and art criticism (like much music, poetry, material history, food, physics, and everything else) is esoteric and difficult. When this difficult art and criticism clicks with a viewer or reader, it is often a powerful moment.

The point of art and art criticism is not to be accessible to the widest possible audience. That is the point of crappy Hollywood movies.

I see this as different - the brightly lit, window-walled diner is a beacon and an oasis. You’d see it blocks away on a dark street; it welcomes. The people are not any more hunched than one would expect for sitting at a counter. The counterman is both working and talking with the people; he is engaged on a human level.

Barry — Well there you go. Interesting idea, understandably conveyed. Please switch fields and become an art critic.

A brilliant film on the subject: http://peterrosepicture.com/movie.php?id=9&type=quicktime

“….critical heuristics whose hypostesized intrusions into a species-specific spatio-temporal domain is enjoined by ironic instantiation.”

I had an Aha-Erlebnis regarding Hopper some years ago when I realized I had the sense, in a number of his paintings, of being drawn into an unseen or obscured space. For example, I get the sense in NIGHTHAWKS of going past the round corner of the building and into the space that is largely obscured by the light reflected from the window behind the man and the woman (whom I have always interpreted as a prostitute and her pimp). (I would say ‘the eye gets drawn into an unseen space in many of his paintings, but that formulation does sound a little paradoxical.) The emphasis on unseen space contributes a huge amount to the effect of his paintings.

Tom Wolfe has made a career of being an insufferable crank with a broken CAPS LOCK key, but I thought his particular brand of patrician venom found a worthy target in the art criticism industry when he wrote The Painted Word.

Once you have to explain a painting (or any other work of human hands) in order to appreciate it, meh.

I’ve liked Hopper since I first saw an original the first time. He has a subtle air that is real. When I walked around in the bad parts of cities, I registered people and buildings just as Hopper painted them. Not in focus even though they were there. Everything is a little blurry because you are listening for anything unexpected, looking for danger, you can’t focus on the non-dangerous. The reality of big city life.

I like Nighthawks because I like it. It evokes some of the same emotions in me that Aaron Copland’s Quiet City evokes. Both remind me of working the graveyard shift in a coffee shop not terribly different from Hopper’s, except that it was on an Interstate exit rather than a city corner.

I found Robert Hughes to be the most accessible of art historians and critics, his Shock of the New on Modern Art is recommended, also his books & TV series. I like Sister Wendy also.

Hughes’ Barcelona is one of the best books I have read in recent years. It shows his amazing range of knowledge about culture, food, art and architecture, with clear exposition throughout.

Art criticism I don’t know, but I spent a few years working on a Ph.D. in English, where the same problem recurs. The basic problem is Sturgeon’s Law: 90% of criticism is crap.

Thus, it’s possible that for a given artist like Hopper, there may be *no* good criticism written, or the good stuff may be obscure (hidden away in some journal). One generally does better to latch onto a good critic and then read him about whatever; learning his way of looking at art could then make Hopper more interesting. If you like Robert Hughes, read everything you can find by Hughes.

I would add, re: “I like it because I like it,” that there is surely a little more to be said. Looking at art, or reading a book, is partly what you bring to it; there are reasons why you like A but not B, but some of the reasons have to do with your own personality and history.

… I am too rusty to think of much good lit-crit: Empson in 7 Types of Ambiguity, Vargas Llosa’s great book on Madame Bovary (The Perpetual Orgy), come to mind, along with usual suspects like Wilson and Trilling.

N.b. that I am not knocking literary theory, which can indeed be obscure; it suffers from a lack of gifted expositors, but that’s true of a lot of philosophical writing. But theory and criticism are not always the same thing.

To add a voice in support of Hughes, his biography of Goya was eye-opening for me; it gave me “new things to notice”, not just about Goya himself, but about portraiture generally—a genre that I’d previously fast-walked past in order to get to the modernist stuff I understood and had a language for.

art criticism is generally the act of blaming Rorschach for what the critic chooses to perceive in the blots of ink (this operative principle has been codified into law by the Supreme Court decision in NEA v Finley - 1998… in an 8-1 majority opinion, only Souter dissenting)

some art criticism is, like any other literary work, better than others, some much much worse, most just mediocre somewhere in between (and even the really good critics have bad days)

criticism of criticism is why god made blogs

[...] Because of all this, and because I enjoy art and art criticism immensely, it kind of annoys me when Social scientists dip their big toe into art history and then pronounce it vapid, with no real or actual [...]