They did things differently there.

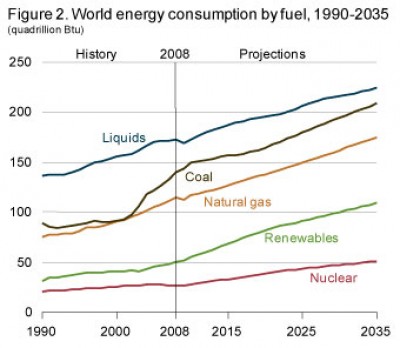

A scary chart from the US Energy Information Administration (via Ezra Klein):

The problem is, it’s rubbish, at least as far as renewables are concerned.

What they did was lazily take the past growth rate for all renewables (about 3%) and project it into the future. The past of renewables is dominated by hydropower, with limited growth potential. However, the category includes wind (compound growth rate 28% over 10 years) and solar PV (compound growth rate 35%). Don’t believe me? Check here.

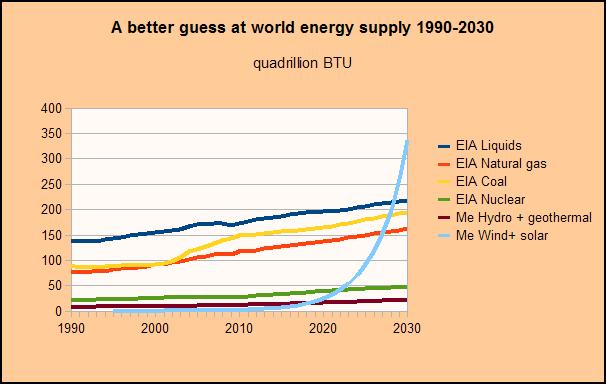

Applying the EIA’s shoddy methods, I split the renewables into “hydro and geothermal” (growth rate 3%) and “wind and PV” (combined growth rate 29%), using data from the BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2011. Projecting these historical rates I got this much more cheerful chart:

Spreadsheet with data and working here.

I don’t ask you to believe this armchair exercise. Wind energy for one may well tend to a constant-returns plateau as the technology matures; solar power will eventually run into land use conflicts; and above 20% or so penetration the need to balance all intermittent power sources becomes an increasingly expensive constraint. All such problems lie ten years ahead, but will no doubt become significant after that.

But it’s far less unrealistic than the EIA projection. This is based on the fallacy that there is a technology called “renewable energy”. There isn’t. Hydro, wind, solar, geothermal and biomass - and that’s leaving out solar thermal, OTEC, wave, tidal, and hot dry rock geothermal, which are so far invisible in the numbers - are far more different from each other than are oil, gas, and coal. Each technology will follow its own learning curve. You cannot sensibly aggregate them ex ante.

BTW, the fact that the prospects for affordable renewable energy supply are very good is not a reason for complacency. The amount of time we have to stop global warming shrinks as we (that is, those of us prepared to make the effort or listen to the qualified) understand more. There’s not much time left to close the coal mines and recycle the Hummers.

*********************************

Alert readers will notice my starting total for renewables is a lot lower than the EIA’s. I haven’t bothered to reconcile them as my demonstration works on BP’s lower numbers. Incidentally, my 29% combined growth rate for solar and wind is itself an underestimate for the reasons I describe: it’s dominated by the greater installed base of wind. Recent 5-year growth rates are higher for all renewables except hydro than the 15-year ones I used.

Isn’t there a little problem in there, that up until now, ‘renewable’ energy has been massively subsidized? Something we could only afford to do so long as it remained a minor part of the energy equation. Unless the ‘renewables’ magically become 5-6 times cheaper per 24 hour reliable KWH, your projected growth for them would bankrupt us before 2030.

Furthermore, I believe I’ve read recently that the theoretical limit for the available amount of wind power is actually quite low compared to current energy usage. You’d actually be slowing down the wind enough to disrupt weather patterns before you displaced much of the grid’s requirements.

Contraception is the highest-leverage energy conservation technology

Brett: clutching at straws. The subsidies have been going down in Europe, correctly and predictably, since their purpose was as much to speed up the learning curve as to stand in for an optimal carbon tax. Where do you get “5/6″ times cheaper? EIA data here: onshore wind is now competitive with anything else on a levelized basis before subsidies, but counting an implicit $15 a ton carbon tax (a prudent scenario for an investor in a new fossil power station). Solar PV is twice the levelized cost but is improving faster.

“I believe I’ve read recently that… you’d actually be slowing down the wind enough to disrupt weather patterns before you displaced much of the grid’s requirements.”

Where? In the National Inquirer? Sure, you can get local effects. The authors of this study aren’t alarmed about the global ones, on the terawatt scale.

“solar power will eventually run into land use conflicts; and above 20% or so penetration the need to balance all intermittent power sources becomes an increasingly expensive constraint. ”

It’s been pointed out (see Charlie Stross’ blog, the latest post) that rooftops give a tremendous amount of space available, with only minor conflicts, and minimal transmission losses. A lot of balance can be done using individual balancing units, especially for larger buildlings (e.g., use peak PV to chill water, then use the water to run the AC; this allows noon-time power to be used later in the afteroon).

And if one assumes that variability in price and availability become larger and larger, the advantages of renewables increase.

Texas has the largest number of wind turbines of any single state.

This summer, when the grid was on the edge of brown-outs and black-outs, the turbines were producing at less than 10% capacity.

What straws? Removing subsidies is only important when they are for renewables. For gas and oil, it would be called raising taxes.

Barry: I don’t deny the roof opportunity, and I did blog three years ago about car parks. I’m waiting for prices to drop to €1 a watt, and for reverse metering, before I put a kw on my Spanish carport: the former will happen before the latter, perhaps as soon as next year. As I said, the space problem is years ahead - I was just pointing it out as one of the things which will eventually stop the increasing returns.

Charles WT: the solution to local imbalances is a national electricity grid, not going back to destroying the climate with fossil fuels. I suppose the electricity peak in Texas is in summer for AC, not winter for heating, as in the windier Dakotas. Texas can and presumably someday will build more solar plants.

Estimating maximum global land surface wind power extractability and associated climatic consequences

“Abstract. The availability of wind power for renewable energy extraction is ultimately limited by how much kinetic energy is generated by natural processes within the Earth system and by fundamental limits of how much of the wind power can be extracted. Here we use these considerations to provide a maximum estimate of wind power availability over land. We use several different methods. First, we outline the processes associated with wind power generation and extraction with a simple power transfer hierarchy based on the assumption that available wind power will not geographically vary with increased extraction for an estimate of 68 TW. Second, we set up a simple momentum balance model to estimate maximum extractability which we then apply to reanalysis climate data, yielding an estimate of 21 TW. Third, we perform general circulation model simulations in which we extract different amounts of momentum from the atmospheric boundary layer to obtain a maximum estimate of how much power can be extracted, yielding 18–34 TW. These three methods consistently yield maximum estimates in the range of 18–68 TW and are notably less than recent estimates that claim abundant wind power availability. Furthermore, we show with the general circulation model simulations that some climatic effects at maximum wind power extraction are similar in magnitude to those associated with a doubling of atmospheric CO2. We conclude that in order to understand fundamental limits to renewable energy resources, as well as the impacts of their utilization, it is imperative to use a “top-down” thermodynamic Earth system perspective, rather than the more common “bottom-up” engineering approach.”

So, Brett, what is your holistic view of the issue and how to solve it?

My answer is simple. I’m with Joel Hanes — the planet cannot sustain 7 billion people living as we do now, and the intelligent thing to do is move it towards half billion people, all living better than we do now.

But I suspect that you find that answer anathema for a dozen different reasons, so what do you actually believe?

OK, sure, you believe global warming is a myth. Presumably you think we should extract all the oil in the arctic, and start fighting over who gets to explore Antarctica for oil. But then what? Once we have frakked every shale in the world, burnt every last peat bog, extracted all the methane clathrates, then what? Are you willing to accept that at some point the process ends, or not? If not, why not?

If it does end,

- when do you believe the end occurs? What is this date based on?

- why not begin preparing for it now? Is your basically an “I’ve got mine” mentality — as long as it runs out after you’re dead, screw those suckers (including your descendants). If they were too stupid to be born I’m the 20th century, they deserve what they have coming?

Brett: Interesting link. OK, not the National Enquirer. Miller’s lower bound on the upper limit of extractable wind power is 18 TW (I assume continuous), which by my calculation is 538 quadrillion Btus per year: off the top of both charts, and a similar order of magnitude to current total global energy supply. I can’t get the link to the full paper to work so I don’t know what they mean by “some climatic effects”. The Keith paper predicts zero increase in mean global temperature from wind energy extraction. The climate scientists should continue working on this; no free passes. For now, since we know carbon emissions are dangerous, and the risks from terawatt-scale deployment of wind are speculative, I don’t see the case for discouraging wind now.

I don’t think so.

Your projection is, on the one hand, that coal, oil, and gas will continue to grow on the same straight line for the next 20 years; by which time renewables will total almost TWICE as much as all of them combined.

Care to make a side bet on it?

Maynard, my “holistic view” is that it’s a crying shame to burn oil, when it’s got so many more valuable uses. In the short run nuclear is probably the energy source with the least environmental impact, the smallest footprint. In the long run solar is inevitable. Pushing the energy of the future before it’s ready isn’t the smartest of ideas, though. Forced transitions are wasteful transitions.

And I’d like to hear your plan for getting from 7 billion to a half billion in less than two centuries, without the total collapse of civilization. 7 billion better be sustainable, we’re going to be at something like that for a long time to come, even if we do reduce our population at any non-apocalyptic rate. I’ve got no pre-conceived idea of what the ideal human population is, but rapid changes downward are literally murderous to accomplish.

So, unsurprisingly, Brett’s “holistic view” is that the market will figure it out, without any “forced transition” by big, evil liberal guvmint.

Sadly, for much of the right wing, the holistic view is, “Why worry? The Rapture will deliver us.”

Glibertarian or Theocrat - pick your poison.

James Wimberley: “But it’s far less unrealistic than the EIA projection.”

Not really. If it turns out that renewables achieve the rapid growth you project, shouldn’t that negatively impact the growth of the other categories?

This is of course a problem both with your projection and the one you criticize. But your’s magnifies the problem by showing one category exploding in use to a point where it dominates, without impacting use of the alternatives.

Blake: Either is better than a Procrustian with an ambition to have 6.6 billion beds.

TS: Of course. My projection is (like I said) a demonstration that the EIA one must be wrong, not a coherent model itself. Doing it properly, you would start with a projection of total demand and estimate the mix within it, using elasticities of substitution as the relative prices of fossil and renewable sources continue to change. Another thing wrong with the EIA scenario is that it assumes away peak oil: oil can’t grow if it isn’t there, so the price must rise by Econ 101.

In fact the substitution may not be a continuous curve: there’s probably a tipping-point price at which everybody puts a solar panel on their roof, Republican politicians learn to love fat-cat solar entrepreneurs, and Brett starts worrying about albedo changes ruining the climate.

James, the amount of land covered by artificial structures actually is large enough for our choices as to it’s albedo to have climate implications on a par with CO2. That’s why I’ve previously asked why we don’t regulate roofing colors as an easy (partial) fix for global warming. Grind chalk into our black-top.

At some point you’ve got to ask why people are bypassing the low hanging fruit in favor of chopping down the tree to reach something at it’s top.

Oh, and any comments on Maynard’s proposal for a half billion population, as a solution to “sustainability”? It really does have massive problems, and yet you get environmentalists talking about things like that all the time.

“Glibertarian or Theocrat – pick your poison.”

DO NOT FEED THE TROLL.

Hmm. The energy-extraction arguments would seem to suggest that, properly sited (!) wind turbines could moderate a significant part of the extreme-weather effects of global warming. At $5-20B per extreme event, that might be a good investment if you could monetize it.