A recent study placing the costs of murder at $17.25 million is attracting a great deal of attention. I hope it will help make the case for crime prevention initiatives at a time of diminishing state budgets.

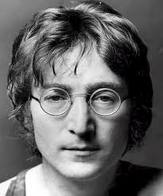

As with many cost-benefit studies, the number itself cannot convey the human impact of what it is estimating in economic terms. So consider this: If he hadn’t been murdered, today would have been John Lennon’s 70th birthday.

Tags: John Lennon

[...] This post was mentioned on Twitter by fadsandfancies.com, fadsandfancies.com. fadsandfancies.com said: Blogfeed: What Murder Costs Us: A recent study placing the costs of murder at $17.5 million is attracting a great… http://bit.ly/d42cfk [...]

Hi Keith. Do you happen to know anything about the composition of that $17.25 million? When I read the piece you linked and didn’t find it, I looked a bit further but was met by a $30 pay wall for a PDF of the study and stopped.

The problem is this. Some of the most effective crime prevention initiatives involve early intervention strategies. Politicians are not likely to invest in these, however, because they won’t pay dividends in their current election cycle. Politicians want results now. This is why I’m skeptical of the whole “justice reinvestment” movement, where politicians would reduce prison populations through effective alternatives and then theoretically reinvest the savings into early intervention strategies. This type of reinvestment will never happen in this economy though. Any savings realized from de-carceration strategies will only go towards balancing budgets and reducing deficits. The types of crime prevention strategies that politicians will more realistically be looking to (and should look to) involve things like more effective policing strategies, better use of crime prevention technology, and innovations in community corrections like HOPE in Hawaii.

Steve (and anyone else who is interested)

Go here, and click on Dr. DeLisi’s paper “murder by the numbers…”

http://www.soc.iastate.edu/staff/delisi/articles.html

Those estimates miss the two biggest costs: the value of the lost life to the person leading it and the avoidance costs incurred by people acting to avoid being victimized. The murder number is huge anyway, but most “cost-of-crime” estimates grossly undervalue the prevention of rape, aggravated assault, and residential burglary.

“those estimates miss the two biggest costs: the value of the lost life to the person leading it…”

Mark, not to get too meta-physical, but if someone believes in God and that he/she is going to paradise upon death then wouldn’t murder be a benefit and not a cost to that person. I value my life in heaven more than I value it here on earth. Don’t get me wrong, I love life here and value it very much, but under my worldview being murdered would just usher me into a better, more valuable paradise in the presence of God, and thus the fractional difference between the value of my life here and the value of my life in the after-life would be an offset benefit to the total cost of my murder.

I completely agree on the large avoidance costs incurred by people acting to avoid victimization though. I also agree that these and other estimates I’ve seen (e.g, Mark Cohen’s work) on the cost of rape and other serious crimes are grossly undervalued.

Bux -

If someone truly held the worldview that you describe, wouldn’t they view the murder of a relative or friend with equanimity? Aside from a handful Amish, I can’t think of any examples of this in my 58 years on the American part of the planet.

Michael, I have no personal experience with murder, but I can tell you that most of the Christians I know view the death of a friend or family member with “equanimity”. The devout Anglican author Samuel Johnson once defined equanimity as the “evenness of mind, neither elevated nor depressed”. His definition resonates with my Christian experience with death. On the one hand we are saddened by the loss of a loved one, but on the other hand we always recognize that “God works all things for the good of those who love him” and that our loved ones have gone on to a much better place. We seek to balance our rational response to this range of emotions and find a sober sense of purpose in death. It is the equanimity of the idea that “God is good all the time, all the time God is good”. A good example for me is when I traded my first car for a new car. I missed my first car when I got rid of it. It had a non-zero value to me, mostly sentimental. But I traded it in for a better car that ultimately costed me less financially and one that came to hold equal sentimental value with my first car. So this transaction which netted me a gain, still held a sense of temporary loss tamed by the hope for the gain I was receiving in the new car. Of course I agree with you that the Amish community approaches death with much more equanimity than other religious groups, such as evangelical Christianity. But this to me is a sign of our weakened faith. We succomb to our fallible human emotions and lack faith in what we espouse to be true. I know some truly exemplary Christian folks who show a strong faith in the presence of death though, demonstating equanimity of mind and emotion that is consistent with the principles of truth they espouse with their lips. Just look to the early church leaders (e.g., the 16th century protestant reformers) who went to their death with calm and confidence. History is replete with examples, but of course that was a time when people actually really believed that there is a heaven and a hell, and not just espoused it in word. I think of Jonathan Edward’s “Sinners In The Hands of an Angry God” in this regard. Read that sermon, look at the language he uses about hell, and read about the historical accounting of his delivery of this sermon (folks were passing out and wailing in fear because they really did believe hell was a real place). So I’m not sure what exactly you mean by “equanimity” here, but I would disagree that only the Amish community would view murder with equanimity.