I´m surprised to find myself understanding anything Hegel wrote but this one is interesting, on the artistic representation of Jesus.

But where “his Divinity should break out from his human personality,” Hegel writes, “painting comes up against new difficulties.”

(I couldn´t locate the citation in the unintelligible full e-text).

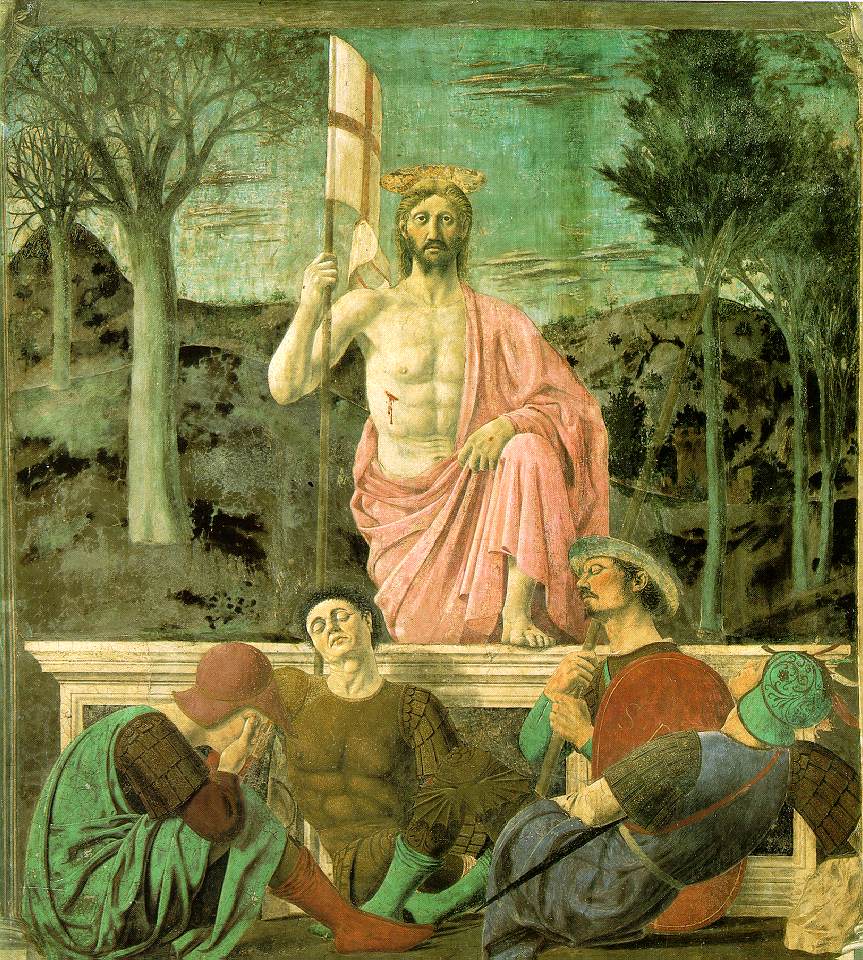

It´s a surprise how little Christian art deals with the Resurrection: the central counter-intuitive claim of fact my religion makes. Compared to the thousands of Annunciations, Nativities, Wise Men, and Passions, at least one in every Catholic and Orthodox church, how many Resurrections are there? I linked to this superb anonymous fresco in the Chora church in Istanbul a while ago in my first-ever post for the RBC (thanks again Mark); Michael last year to a panel of the Isenheim Altar by Grünewald. The missing one is Piero della Francesca´s masterpiece in Borgo San Sepolcro:

Piero wrote the treatise on perspective, and he plays very sophisticated games here. The picture apparently has two vanishing lines, a lower one for the sleeping guards and a higher one for the rising Christ; and the lines of the trees point forward out of the picture to the viewer. This is not happening in a normal world. Think how very easily it could become ridiculous (Shazzam! With one bound he was free!), but it isn´t at all.

I don´t however agree with Hegel´s prosaic(!) explanation that the theme is just too difficult. St. Luke´s annunciation story also describes a magical, otherworldly event, but this hasn´t deterred many patrons and artists from having a go at its depiction. So there are lots of bad Annunciations. The Transfiguration is a standard theme in Orthodox icons; I bought one from a monk´s workshop in Cyprus twenty years ago. Where are all the bad Resurrections?

There are two possible specific explanations. One is that the New Testament offers no eyewitness accounts, so artists are on their own. For a thousand years, using initiative on this scale was doctrinally risky. You (and your patron) could be accused of being a Monophysite for a painting like Grünewald´s, or an Arian for one like Piero´s. Both men were oddballs whose main livelihood came from other things; Piero as a mathematician and Grünewald a millwright, a humble but indispensable technician (compare today: computer network repairman). They were of course also geniuses capable of meeting Hegel´s challenge.

The other factor that called for a lot of nerve is that the story is on the face of it incredible. The Gospels insist on the repeated incredulity and doubts of many of the disciples, not just Thomas. The problem did not go away: Paul, in 1 Corinthians 15:12, argues with - not anathematises - some members of the infant church in Corinth who ¨say that there is no resurrection of the dead¨. Substantial minorities of American (and no doubt other) Catholics and Protestants today do not associate Easter with the resurrection claim.

Any artist taking on the Resurrection has to confront this. A purely naturalist human sympathy can carry you through the Nativity and the Cruxifixion - Michaelangelo´s (to me) secular Pietàs are magnificent examples. But for the Resurrection, you have to deal with your own doubts and those of your viewers, put yourself in Thomas´ shoes, and use the doubt, Zen-style, to create an unearthly yet aesthetically convincing image. A straight unbeliever cannot do this as a technical exercise. The combination of the technical and spiritual qualities required to take on the Resurrection theme is very rare.

Swift Loris says

"Where are all the bad Resurrections?"

Wikimedia Commons has a big collection of Resurrection artworks (including sculpture and stained glass):

http://tinyurl.com/yjetplq

Plenty of bad ones, plus some very nice ones, although the three you cite are hard to beat.

I like this quiet, earthy Rembrandt, in which Christ appears almost to be trying to sneak past the guards:

http://tinyurl.com/yjpkzjy

Want a bad one? Here's a Resurrection by Coypel, 1700:

http://tinyurl.com/ygy5tpq

This painting was featured on the cover of Time's Easter issue in 1995:

http://www.time.com/time/covers/0,16641,19950410,…

Yikes…

Another one I like, by Multscher, 1437:

http://tinyurl.com/yccmfav

Neat angle, looking down on a rather beat-up Christ as he's climbing out of the tomb. He seems to be telling an anxious God the Father, "Hold on, here I come!"

It's interesting how many of them feature Christ with, literally, one foot in the grave, presumably to emphasize the moment of transition from death to new life. Where did that iconographic detail come from? (And is it perhaps the source of the common phrase? Quite a twist, if so.)

Dave Trowbridge says

Both your explanations seem reasonable.

It's interesting to note that in the original version of Mark's gospel, there are not even any post-resurrection appearances, just the empty tomb. And Crossan and other historical-Jesus scholars postulate a lost gospel attributed to Peter (the Cross Gospel) that does depict the resurrection, albeit in highly symbolic terms.

bz says

For what it may be worth, Forest Lawn in Glendale features a daily presentation of a large painting depicting the Resurrection, produced by American artist Robert Clark in 1965 (presentation complete with curtain-opening and dramatic narration). I first saw it on a field trip for a painting class at Art Center back around 1970. At least technically speaking, as a work of craft, it was pretty impressive (to me as a student, anyway). The symbolism, however, struck me as pretty unimaginatively literal, although maybe that's appropriate for the target audience. The link shows a small jpeg, and detail.

http://www.forestlawn.com/Special-Events-And-Faci…

Robert Waldmann says

The exception proves the rule. My first reaction on reading the first lines of this post was "No. What about the Isenheim Altar by Grünewald."

OK actually what about the alter with the very famous and gruesome crucifixion on the outer panels which technically contains a painting of the resurrection on the inner panels but almost no one knows it and I remember seeing a photograph of it in a book and it was painted by someone with a German name.

That is, I am very non expert on art history, yet the same painting appeared in my almost blank slate artmemory and in this post.

sd says

I would tend to buy into the "no eyewitness accounts" explanation, moreso than the "incredible" explanation. The actual Resurrection isn't described in the Gospels - only the many post-Resurrection appearances.

The one thing I'll say about the "incredible" explanation is that thje Gospel accounts of the Resurrected (Glorified" body of Jesus are inherently mysterious. Its clearly a physical body (Thomas touches the wounds; Jesus eats fish), but its also somehow strange and otherworldly. The annunciation, on the other hand, though supernatural, is described in straightforward terms. You can believe it or not but its clear that what you're being asked to believe is describable. The Resurrection is an altogether different type of phenomenon.

James Wimberley says

The Isenheim Altar (now in the Unterlinden Museum in Colmar; vaut le voyage, and you are not distracted by the far inferior reat of the collection,which only serves to highlight Grünewald´s powerful masterpiece) is a very large and complex Chinese-box structure. There are two sets of fold-out panels on which he painted, and behind them a not very interesting sculpture. I suppose the panels were opened and closed with the seasons of the church year.

Grünewald combines a full Renaissance technique with a deeply mediaeval sensibility. What you first confront is the tortured, apparently gangrenous, but superbly physiqued Christ in the Cruxifixion, who is, or seems to be, greater than life-size. Mary by his feet is fainting with grief, held up by John. The image has the impact of a truck.

James Wimberley says

Swift Loris: Your post was held up in an approval queue because of all the links, sorry for the delay.

The Wikimedia link does make me qualify the factual premise a little; but still, 14 paintings (with Fra Angelico, but excluding the two Rembrandts as not of the Resurrection as an event) and 61 sculptures ia far less than the parallel entries for the Annunciation (44 paintings), the Nativity (49 paintings), and the Cruxifixion (179 paintings). Anecdotally, my observation of a lot of art galleries and churches al around Europe is that the overall disparity of the themes in church art is much, much greater.

The Wikimedia sample makes my point about quality. Many are frankly embarrassing. Even Della Robbia fails. Fra Angelico, as you would expect, has a fine and subtle take, placing the resurrected Christ in an oval frame-within-the-frame that takes him half out of the world of the women at the empty tomb..

John A Arkansawyer says

James, you'll find this book interesting.

Swift Loris says

James, I think you missed the main Wikimedia category below the subcategory listings; there are 114 works listed (some duplicates, not all of the Resurrection per se), mostly paintings.

You're right about the Rembrandt I linked to; I thought the folks around the tomb were guards, but looking more closely, they're women, and there's an angel to the far right. He's combined Noli mi tangere with Women at the Tomb (as Fra Angelico combines the Resurrection with Women at the Tomb-I really like the mystery of that one).

Check out this very original take from Cuyp, 1640:

http://tinyurl.com/yctutb7

And this Bouts, 1455, is quite fine, IMHO (Christ's confront reminds me of that in Piero):

http://tinyurl.com/yehzgg5

El Greco did his usual thing:

http://tinyurl.com/yhq7d4j

Some other nice paintings in that main category-and a lot of awful ones, no question. Generally speaking, the quieter interpretations seem to me more successful artistically than the dramatic ones, which is odd considering the nature of the event.

James Wimberley says

Thanks for this, especially Bouts and Cuyp. The Rembrandt is indeed clearly about Mary Magdalene´s encounter with the gardener in John; you might like Kipling´s OTT but moving story ¨The Gardener¨ in Debits and Credits. The resolution of the numbers question will need actual work by a real art historian.

Swift Loris says

Oh, lovely story, thank you!

I think that's my favorite scene in all Christian art, actually, so tender and poignant, in some versions even verging on the erotic. Wikimedia has a nice collection. I'll just cite one, this extraordinary Dürer woodcut:

http://tinyurl.com/ye55n6y

Enjoyed the trip, thanks for the ticket!

karlg says

The Resurrection certainly hasn't been as popular a subject as some, but I think you underestimate the number of Resurrections out there (and overestimate the Passions, Annunciations, et al). Dig a little deeper and you'll find many more than you expected. That said, Hegel and you are on to something: babies, pretty young women, and meals are accessible subjects, but divinity isn't easy to paint — and even if you do it well, it may not lead to another good commission. Even in Church, crowd-pleasing is a virtue.

Swift Loris says

What surprised me a little as I looked through reproductions of Resurrection artworks was how many of the artists didn't paint divinity: the paintings don't tell the viewer who doesn't know the story that a supernatural event is taking place. It's just a guy climbing out of a box, which isn't even obviously a tomb in all cases. There are usually people around him, in some cases appearing surprised, although it's not always clear why; in others the people are sound asleep. The Piero is a case in point. If you didn't know the painting was of the Resurrection, what would you think was happening?

Others, like the Grünewald, hit you over the head with the miraculous nature of the event and the divinity of the central personage. What led the various artists to make such different choices?

Geoffrey Allen says

Of course you're right, though I did find an interesting selection of Resurrections on http://www.bible-art.info/Resurrection.htm. I liked the Rembrandt as well as Fra Angelico and Grünewald.

The inherent difficulty of the subject may be part of the reason. But I believe Western Christianity embraced a death-centred mentality from mediaeval times (the most gruesome manifestations are in the "Holy Week" processions in southern Spain, a part of the world where the Resurrection seems to be almost totally ignored). In contrast, the older (pre-1000) Christian basilicas typically emphasise the "Christ in glory" (Pantokrator), usually depicted in the half-vault over the altar. The Eastern Churches seem to have preserved this awareness of the living Christ much more than in the West.

Swift Loris says

Oh, man, gotta add this: I just looked again at the lovely Multscher painting I linked to in my first post and realized that Christ isn't climbing out of an open tomb-he's emerging right through the closed lid. Look at the hand of the guard in the upper left resting on the lid, the way Christ's robe falls on it, and how his left leg disappears into the stone:

http://tinyurl.com/yccmfav

Talk about yer divinity! This is one of the "quieter" Resurrection paintings, but if you look at it closely, you don't even have to know the story to realize something extraordinary is happening. I'm just blown away by the ingenious subtlety of it. I haven't seen any other paintings that picture the event this way.

martin says

From a friend - art historian

"As for the Resurrection: scenes of the Passion and Resurrection occur on either side of Christ on the great painted panel crosses from the 12th cent. to the beginning of the 14th cent. in Italy. The scene is also found in the tympana in Gothic cathedrals from the end of the 13th cent. It is curious that Gertrud Schiller in her 2 vols. of the Iconography of Christian Art did not include the theme, but then she meant to write at least 3 more volumes. Certainly there are noteworthy 15th/early 16th versions by Durer, Raphael (?), Mantegna (?).

I think that there were reasons of dogma - the Counter Reformation's insistence on the human and pathetic nature of Christ (not the divine), the identification with the faith and tribulations of the saints."